Faculty diversity: the road ahead

Campus pursues new initiatives, but time is of the essence, says equity chief

6 February 2003

Ten years from now, there will be some 800 new ladder-rank faculty teaching classes and conducting research at Berkeley. Thatís the number of new hires that the campus anticipates making, to accommodate a major expansion in student enrollment and to make up for normal rates of attrition.

Angelica Stacy, associate vice provost for faculty equity. (Cathy Cockrell photo) |

For chemistry professor Angelica Stacy, the campusís associate vice provost for faculty equity, the enrollment "tidal wave" ahead, and the accompanying hiring wave, bring opportunity ó a chance to hasten progress toward a diverse, high-caliber faculty enriched by the talents and perspectives of women and minorities. In a recent conversation with the Berkeleyan, Stacy discussed where we stand currently; how faculty composition affects the academic enterprise; obstacles to progress; and initiatives in motion.

What is the current composition of the faculty and administration, by gender and ethnicity?

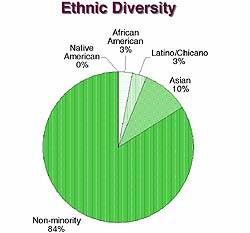

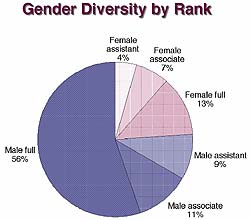

The overall composition of the tenure-track faculty [assistant through full professor] is 76-percent male and 84-percent white. These percentages have remained largely the same over the past decade for underrepresented minorities, with small improvements in the percentages of women and Asian faculty. For the senior academic administration, out of 21 academic deans there is one female and one minority. Out of 63 departmental chairs, 16 are female and 5 are minority.

What have been the hiring trends? Have attempts to increase diversity had an impact?

The hiring of women declined in the late í90s, after the passage of Prop. 209. But renewed commitment by the campus has begun to pay off, and the numbers are getting close to where they were a decade ago. For underrepresented minorities, the numbers go up and down, but overall thereís been no progress. [See "The past decade," page 6.]

Currently, Berkeley has 159 Asian, 2 Native American (0.13 percent, rounded here to 0 ), 39 African American, and 53 Latino/Chicano ladder-rank faculty. Women of color constitute about one quarter of the minority faculty, or 4 percent of all ladder-rank faculty. |

We are doing slightly better than our peer private institutions and slightly worse than our peer public institutions. But we are Berkeley, and we strive to be the best at everything we do. Moreover, Berkeley is a public institution in the most diverse state in the country ó a land-grant institution supported in part by the state ó and we feel obligated to reflect the diversity of the state in our hiring.

What commitment has the campus leadership made to faculty-diversity efforts?

Chancellor Berdahl and members of the upper administration are all committed to improving faculty diversity. The chancellor played a key role, a while back, in a meeting at MIT of leaders from top research universities around the country, focusing on faculty gender equity. These leaders came out with a very strong public statement that faculty diversity would be among their highest priorities. In line with that commitment, the campus has a number of new initiatives. [See "Whatís in motion?"]

Why are so few underrepresented minority faculty being hired? Is the applicant pool as limited as the numbers would suggest?

The pool is small, but it isnít zero. You only have to find a few good candidates to make a difference. We need to do a better job of attracting candidates to the Berkeley campus. I think thatís going to require understanding the choices that minority scholars are making.

For example, if youíre one of the first in your family to move on, if your family doesnít understand what youíre doing, and if family itself is something really important to you, you might not consider leaving your home state to attend graduate school. And so you may truly be outstanding, really stellar, but youíre not in the typical environments where we look for faculty. I think we need to begin looking beyond the usual places for talent.For minority scholars who are offered a job at Berkeley, what is the rate of acceptance?

Berkeley is used to having scholars accept our job offers. The acceptance rate overall is close to 75 percent. Whatís striking and of concern is that although we made 11 offers to African American candidates in the past two years, only 5 accepted.

Why is that? At least three top minority scholars have said they turned us down because they found colleagues who shared their research interests at another institution. This information has led us to consider trying to coordinate the hiring of a cluster of top scholars, in different disciplines, whose research addresses a common theme. [See "Cluster hiring", page 7.] An example might be research on race and ethnicity in American society.

We are also concerned that if there are few women or minority faculty in a unit, potential candidates are going to question whether the climate is right for them. To that end, we are doing a campus-climate survey on the degree to which all faculty feel they are full participants in the campus community. We hope to have preliminary results on that by the end of the semester.

The majority of Berkeleyís ladder-rank faculty are male full professors. The number of male assistant professors and male associate professors is roughly equal. For women faculty, the associate professor group is larger than the assistant professor group, indicating slower progress through the ranks. |

In the past 10 years, more than half of the faculty hired in the College of Environmental Design, and nearly half in the College of Letters & Scienceís arts and humanities division have been female. The College of Engineering hired 5 women out of 15 hires in the past two years. This is really impressive, given that only 18 percent of the PhDs in engineering are granted to women.

Several colleges and schools have been especially proactive in recruiting underrepresented minority faculty. The social sciences and professional schools have done reasonably well in putting forth effort, if not in increasing the numbers. One thing that these departments and schools are doing is to request authorization to hire in areas that will expand the diversity of research.

Why is it important to do that?

The academic research that goes on is defined, by and large, by the scholars who are here. As we expand the diversity of scholars, it broadens the research that is pursued. New areas of literature, music, and culture are explored, and there are new perspectives on history, society, education, and policy. In the sciences, you find more research on gender- and race-related diseases, and new applications of technology specific to concerns of women and minorities. Iím saying that as minorities and women are included in the academy, it changes the research thatís pursued. This benefits society. Moreover, as research areas expand, youíre going to attract a more diverse group of people.

Once a scholar has been admitted to the academy, does the tenure clock disadvantage caregivers, and women faculty in particular?

For junior faculty, in the beginning of your sixth year youíre reviewed for tenure. So thatís the amount of time you have to begin your scholarly work and have received recognition for this work. Most faculty, at this assistant-professor stage, are between the ages of 28 to 38. Thatís prime time for starting a family. I couldnít imagine a worse time for the tenure clock to be ticking.

UC has one of the best family-leave policies in the country. It applies to both men and women; in fact, more men than women have taken advantage of the policy, to be the prime caregiver for a newborn child.

We need to know how well the policy is working. To that end, my office is conducting studies with Graduate Dean Mary Ann Mason. She has preliminary results showing that, for women scholars, there is a negative correlation between success at work and satisfying their family goals. The opposite is true for men. So becoming an academic comes at a great cost for many women.

Read more stories from the Berkeleyan's Faculty Diversity

package |

The percentage of women hired at Berkeley is roughly equal to the percentage of female applicants. So the answer is clear: if we want to hire more women, we need to get more women to apply. Women are in the PhD pool in large numbers, so there is no shortage of supply. Unfortunately, many top women PhD students, after getting their doctorate at Berkeley, decide that a faculty position at a research university is not for them. So itís clear that we need to do what we can to ensure that the campus is an inclusive environment that is attractive to women scholars. For women, many things point to the need for family-friendly policies. Getting more women in leadership roles is also a key factor.

For minority scholars, the pools are small, so we cannot expect large increases in the numbers of minority applicants. The challenge is more about overcoming the isolation and marginalization that can go with being outnumbered in a department. So as I say, weíre shifting our thinking toward hiring clusters around research agendas of interest to minority scholars. Collaboration will not only aid in recruitment, but also in retention.

In order to maintain our excellence, we simply need to tap all the top talent, not just a limited pool. What a shame to not have all that brain power working at the highest level for the benefit of society. Weíre losing a lot of valuable ideas and perspectives. And thatís what the university is about ó a multiplicity of ideas.