Drake’s Plate hoax confirmed

Historical research reveals names and motive of the mid-1930s hoaxsters —

![]()

| 19 February 2003

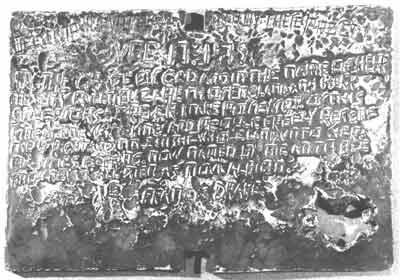

| |  This brass plate, engraved with what appeared to be Francis Drake's 1579 claim to Nova Albion, became California's greatest historic treasure when it was found and authenticated in the 1930s. Though the plate was revealed as a hoax some 40 years later, its origins remained speculative until recent research helped pinpoint the probable perpetrators. Photo courtesy The Bancroft Library |

Researchers who spent a decade digging into one of California’s most infamous hoaxes now say they know who did it — and have a pretty good idea why.

At a Tuesday press conference the researchers revealed what may be the final chapter in the story of a brass marker long dubbed “Drake’s Plate.” The plate, discovered in 1936, purportedly recorded the California coastal landing in 1579 of English explorer Francis Drake and his ship, The Golden Hind. Though it was proclaimed genuine at the time of its discovery and proudly acquired by the Bancroft Library, scientific testing 40 years later determined it to be a fake.

Among the newest findings are that the hoax was created by a group of respected Bay Area men active in regional history and the art world, and that it succeeded despite indirect warnings that the plate was a fake.

These and other findings are published in the latest issue of California History, a publication of the California Historical Society (CHS), by Edward Von der Porten, a nautical historian, archaeologist, and retired maritime-museum director; Raymond Aker, a maritime researcher who died earlier this year; Robert W. Allen, a historical researcher and educator; and James Spitze, an amateur historian.

Their conclusions may surprise many Golden State history buffs who accepted the long-circulating story that the playful E Clampus Vitus historical fraternity (aka the Clampers) was responsible for the prank. The group has bristled at the accusation.

While acknowledging they lack a “smoking gun,” lead author Von der Porten and his fellow researchers cite a wide range of sources that they say point the finger at a band of well-established and respected gentlemen of the day — only one of whom was known to have been a Clamper.

The cast includes:

G. Ezra Dane, a prominent member of both the Clampers and the California Historical Society. He instigated the hoax.

George Haviland Barron, curator of California history at the de Young Museum in San Francisco until 1933 and a leading member of the California Historical Society. He designed the fake plate.

George Clark, an inventor, art critic, appraiser, and friend of Barron’s, who engraved the plate.

Lorenz Noll, an art dealer and restorer, and Western-artifact dealer Albert Dressler. They are believed to have helped with the fluorescent lettering “ECV” applied to the back of the plate.

Herbert Bolton, director of the Bancroft Library from 1920-1940 and Sather Professor of American History at Berkeley. He also was, like Dane, a member of both the California Historical Society and the Clampers. Fascinated by stories about Drake posting a brass plate to mark his entry into California, Bolton was known for telling his students to be on the lookout for it when in Marin County. The plate’s appearance fulfilled Bolton’s dream, and he was thrilled to acquire it for the Bancroft.

Sport brought these men together, although Bolton, the target of the hoax, was unaware of the game. “Spoofing its own members was an accepted part of Clamper fun,” the researchers say, “and the distinguished Professor Bolton was a tempting target.”

Elaborate handiwork

But the organization’s leaders did not sanction the joke, so Dane sought assistance from Barron, Clark, Noll, and Dressler. Barron designed the plate, borrowing most of the text from “The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake,” a detailed account of Drake’s voyage published in 1628. Barron’s friend and neighbor, Clark, reportedly designed the layout for the plate and chiseled the lettering.

The plate was fashioned from common brass, with text carved with a chisel and the letters’ raised edges hammered down. Then the plate was heated over a wood fire to create a dark patina. It was hammered once more, darkened more with dirt, ash, and perhaps more chemicals, and possibly subjected to fire once again and buried for a time. Finally, one of the conspirators — the authors believe it was probably Dane, in cahoots with Noll and Dressler — labeled the plate a Clamper prank by painting “ECV” on the back with fluorescent paint.

The hoaxsters’ handiwork paid off, even more than they had planned, the researchers write: “...the realization that Bolton was almost unquestioningly supporting the plate’s authenticity must soon have changed jubilation to shock and — quickly — deep concern. Their inside joke, intended to be resolved with a good laugh over a dinner table or at a Clamper meeting, had escaped from their control.”

Bolton was not the only one conned. Also taken in was Alan Chickering, a lawyer and president of the CHS, as well as other society officers and members, who donated $3,500 to buy the plate (later donated to the Bancroft). The society’s directors, who authorized publications about the plate, also were fooled.

The tricksters and most of the hoaxed all belonged to the same small world of California-history enthusiasts, the researchers said, making a public confession very difficult. Though the tricksters tried to warn Bolton indirectly, he disregarded the warnings.

About a decade after the plate was found, Lorenz Noll told Albert Shumate — a San Francisco doctor, California historian, and longtime leader of the CHS and the Clampers — what had really happened. He said that Barron, Dressler, himself, and others were involved in what Shumate characterized as an elaborate joke that got terribly out of hand.

‘The final chapter’?

This research “may well be the final chapter in this great mystery,” says Stephen Becker, director of the California Historical Society. He commends the researchers “for their excellent scholarship, for setting the story straight, and helping us all enjoy this wonderful tale of historical fact and fiction.”

The phony plate become a centerpiece of the 1939-1940 Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island, and photographs of it have appeared in textbooks and popular magazines. The discovery location on San Francisco Bay also set off 50 years of fierce debate about where along California’s coast Drake really landed.

For all the confusion and misinformation surrounding the plate, the California History article’s authors say the hoax has had positive impacts that include a wide range of related research and increased public awareness of the state’s explorer-era history.

The fake plate will remain on display at the Bancroft Library, while the real thing, researchers say, may still lie deep beneath the water, rocks, and sand of Drakes Bay.