Unsung, ‘veiled’ Garvey takes center stage

Campus scholar charts the life, times of Pan-African feminist Amy Jacques Garvey

![]()

| 26 February 2003

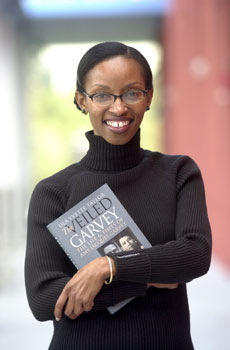

| |  Associate Professor Ula Taylor has written the first book-length biography of Amy Jacques Garvey. Noah Berger photo |

“We are the descendants of a suffering people. We are the descendants of a people determined to suffer no longer. We shall now organize the 400,000,000 Negroes of the world into a vast organization to plant the banner of freedom on the great continent of Africa.”

With such words, the Jamaican-born black leader Marcus Mosiah Garvey, in the early decades of the 20th century, inspired millions across the globe with a program for racial pride, self-reliance, and nationhood for people of African descent. Hailed by many as a “Black Moses,” Marcus Garvey and the organization he founded and led — the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) — are now staples of every survey of African American history.

Yet Garvey’s legacy — the spread of his “Pan African “ program for unity among blacks in Africa and the African diaspora, and its influence on later incarnations of black nationalism — owes much to his second wife, whose name rarely surfaces during yearly celebrations of Black History Month. It is Amy Garvey (né Jacques) — intellectual, writer, Pan Africanist, feminist, activist, wife, and mother — whom Berkeley historian Ula Yvette Taylor brings to light in a new book, “The Veiled Garvey” (University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

Taylor, an associate professor of African American studies, discovered Amy Jacques Garvey as an undergraduate at UCLA, while researching the women’s section of major black newspapers of the 1920s, such as the Chicago Defender and the New York Age. Etiquette and household hints filled most of those pages. Only the UNIA paper, The Negro World, she says, consistently carried political commentary in its women’s section, “Our Women and What They Think.” Amy Jacques Garvey launched and edited the page, and in her editorials — nearly 200 written between 1924 and 1927 — challenged patriarchy, racism, and imperialism.

“The Veiled Garvey: The Life and Times of Amy Jacques Garvey” is the first book-length biography of this important but unsung figure. Born in Jamaica in 1895 to an educated “brown” family, Amy Jacques suffered from bouts of malaria and, in order to live in a malaria-free area, moved in 1917 to Harlem. There she became involved in the UNIA, serving first as a traveling secretary and later as private secretary to its leader, to whom she was married in 1922. The following year, the government brought charges against Marcus Garvey — claiming fraudulent sale of shares in the UNIA’s black steamship line; over the next years he was imprisoned and eventually deported. (A number of factors — including the hostility of J. Edgar Hoover, Marcus Garvey’s lack of business acumen, and the antipathy of other black leaders — are said to have contributed to Garvey’s downfall.)

Thrust by these troubles, in her husband’s absence, into a prominent position in the UNIA, Amy campaigned for his release, kept his words and philosophy before the public, and developed a female Pan Africanist philosophy on the women’s pages of The Negro World.

“She blossomed,” says Taylor, “by honing her journalistic skills, writing commentary on the international situation, and refining her discourse on Jim Crow.” But it was after her husband’s death in 1940, she says, that Amy Jacques Garvey took flight as an independent thinker. While the UNIA lauded the promise of black capitalism, for example, Amy took note of its limitations. And she became less concerned with getting people to join the UNIA, says Taylor, than with getting Pan African ideas into existing organizations.

Treated like a queen

Amy Jacques Garvey also developed a thriving “network of correspondence” Taylor says, with world-renowned black leaders — among them author W.E.B. DuBois; Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana; and the first president of Nigeria, Nnamdi Azikiwe — and helped organize international Pan African conferences. Nkrumah, for one, had studied “The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey,” regarded as a Pan Africanist bible, which Amy Jacques Garvey had edited and published. “When some of these men became heads of state,” says Taylor, “they invited her over and treated her like a queen.”

Taylor’s work on Amy Jacques Garvey, along with her research projects before and since, helps to delineate lines of influence connecting phases of black feminist thought and black political activism through time. In the early ’90s, she was historical consultant for the Hollywood film “Panther,” directed by Mario Van Peebles, and co-wrote the accompanying pictorial book on the Black Panther Party and the movie. She is currently researching the history of the Nation of Islam — which, like Rastafarism, the Black Power movement of the 1960s, and other expressions of black nationalism, was influenced by Garveyism. “When the Nation of Islam started in the 1930s,” she says, “many early members, including Malcolm X’s parents, were former Garveyites.”

The legacy of Garveyism continues to the present day, and Taylor’s new biography pays homage to one who helped shaped its philosophy and spread its message.