A psychologist’s quest

The roots of Stephen Hinshaw’s research on childhood behavioral problems couldn’t be more personal

![]()

| 12 March 2003

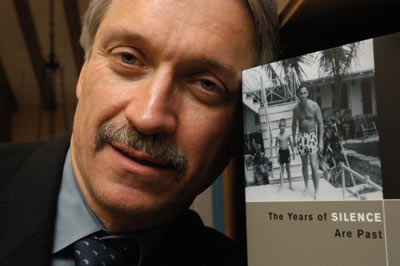

| |  Psychologist Stephen Hinshaw’s latest book tells the story of his father’s long struggle with bipolar disorder — which the younger Hinshaw helped correctly diagnose during his own early years as a clinician. His experience with his father’s illness contributed to his decision to redirect his career focus from medicine to psychology. Peg Skorpinski photo |

Stephen Hinshaw was a premed student at Harvard when his father, a philosophy professor at Ohio State University, first confided in him about his long struggle with mental illness.

“I had not known anything about it,” Hinshaw says, “because the doctors had told him, ‘Never tell the children about mental illness.’ This was a common recommendation in the 1950s, given the general stance of ignorance and shame about severe mental disorder.”

It is a struggle the psychology professor documents in his new book, “The Years of Silence Are Past: My Father’s Life with Bipolar Disorder” (Cambridge). His father’s revelations “changed my experience of him fundamentally, because I got to know him,” Hinshaw says. “And they changed me fundamentally, too.”

The disclosures were often harrowing. “There were no treatments, really, other than basically tying him to bed or, later on, giving him electroshock therapy or the first generation of antipsychotic medications,” Hinshaw says. “And it wasn’t until 20 years after that — after I helped diagnose him in the ’70s — that we finally got him on lithium, an appropriate treatment for bipolar disorder.”

A research focus

The misdiagnosis of his father and the primitive treatments he received led Hinshaw toward psychology instead of medicine. And they have ever since guided his research — most of which has focused on the causes of and treatments for children with hyperactivity and similar behavioral problems.

His quest for more precise diagnoses and treatments began with his dissertation. Against the advice of most professors and advisers, Hinshaw insisted on looking at which treatment combinations work best for children with behavioral problems: medication, some form of psychotherapy, or a combination of the two. His early findings in favor of combined, or “multimodal,” treatments encouraged him to pursue this research thread in future studies.

Hinshaw’s pursuit led, in the 1990s, to his heading at Berkeley one of six centers in a national study of boys and girls with Attention Deficit-Hyperactiv-ity Disorder (ADHD).

“The Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD,” says Hinshaw, “is the largest randomized clinical trial the National Institute of Mental Health has ever conducted” on any psychiatric condition. Its focus was a perfect match with his longstanding interest: to see which treatments work best for which types of children.

For 14 months, 579 children and their families participated in one of four treatment plans: customized and closely monitored medication; a three-pronged “psychosocial” approach; a combination of these two approaches; and mental-health services in the community, which often meant haphazardly monitored medication treatment.

Hinshaw is quick to emphasize that the psychosocial approach did not involve one-on-one therapy. Instead, the three prongs of this approach each took a different tack with the children, their parents, and their teachers. In all three, the focus was on restructuring the children’s environment through more consistent rewards and consequences for their behavior.

Parents were taught, for example, to be more consistent and calm in their discipline, to manage their own anger better, and to reward regularly their kids for improved behavior. (Key behaviors, such as cooperation or reduced arguments, were specifically targeted to each child.)

Teachers were shown ways to help these children focus more and how to give them frequent positive feedback in class. The children themselves were offered academic tutoring, along with group therapy to teach them social skills, such as how to tell when a teacher or playmate is unhappy with them and what to do about it.

Unexpected outcomes

Hinshaw discovered some surprises in the findings. “One key outcome variable was the children’s levels of disruption and aggression at school, because that behavior is very predictive of later delinquency. We found one subgroup of children who, by the end of the study, showed not just improved but actually normal rates of aggressive and disruptive behavior at school.” That subgroup made up more than a third of those in the combination treatment group, which received both medication and the three-pronged psychosocial therapies.

When Hinshaw and his team looked at why this particular subgroup showed such unexpectedly positive outcomes at school, they found another surprise. The successful children’s parents had “significantly improved their discipline styles across the 14 months of treatment,” while the other parents in the combination treatment group had not taken those lessons to heart.

“I think an important message is that parenting still matters,” says Hinshaw. “Even for a condition as genetic as ADHD, you need to change more than the biology; you need to change the setting in which the kid is developing. And it’s the combination of those two things that really makes the difference.”

Multimodal approaches. Nature and nurture. This is the kind of pragmatic revelation Hinshaw lives and works for.

“It’s very personal and compelling,” he says, “because it might make a difference in many people’s lives and families.”