Hearst Museum’s Plato is the real deal

![]()

| 16 April 2003

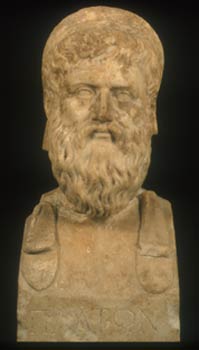

| |  The “Berkeley Plato” depicts the philosopher with fine features, more closely cropped hair, and a less “blocky” head than later likenesses. The herm, on display in the Hearst Museum of Anthropology, is now believed to date to 125 A.D., a replica of an original from about 360 B.C. |

A portrait herm (a bust atop a tall pedestal) of Greek philosopher Plato is emerging from a century of obscurity and disrespect to assume its rightful place in ancient history, thanks to the sleuthing of a Berkeley classics professor.

Last week, Stephen Miller, a specialist in Greek and Roman archaeology, publicly outlined his research and scientific test results that he says show the sculpture purchased for Berkeley’s anthropology museum in 1902 is not a contemporary fake, as long thought.

“We dirt archaeologists,” says Miller, “rarely think about excavating in museums, and yet there are discoveries to be made every time we look at antiquities, wherever they might be.”

The story began in Rome, where classics scholar Alfred Emerson purchased the herm for Phoebe Hearst, benefactress of the Berkeley museum. Emerson was dismissive about the marble bust of Plato and its pedestal, and mentioned it only in passing in a letter to Hearst about his purchases.

Initial museum records note that the herm’s significance was in doubt. But the crowning blow came in 1966, when Berkeley graduate student R.J. Smutney, studying Latin inscriptions, inspected the writings on Plato’s shaft — it had been separated from the head, which couldn’t be found — and declared it a fake.

Miller says he can now prove the opposite. The sculpture dates back to approximately 125 A.D., and is an elegant replica of a Greek original from about 360 B.C.

Miller bases his conclusions on inquiries into several topics, including ribbons that adorn the sculpture; Plato’s writings and what’s known of his life; quotations inscribed on the UC Berkeley Plato; the source of the marble and the quarry’s known time of use; and lettering on the shaft.

The ribbons on the Plato are significant for many reasons, Miller says. One is that modern artists typically have depicted Plato with long tresses, not ribbons. The ribbons also underscore Plato’s known love of athletic competition and visits to Olympic games, his training as a wrestler, his competition at the Isthmian Games, and the ribbons’ association with gymnasiums, the dramatic setting for at least four of Plato’s dialogues.

The sculpture also depicts the philosopher with a puffy, deformed lobe on his left ear. Miller noted that in Plato’s Protagoras, the philosopher referred to admirers of Sparta, who bound their hands in order to box so that their consequently deformed ears would be like those of their heroes. The Berkeley Plato’s bad left ear may indicate the impact of a ferocious swing by a right-handed opponent, Miller says.

Plato’s writings also offer clues to the sculpture’s authenticity. In The Republic, probably written between 380 and 370 B.C., Plato presents his notion of the immortality of the soul. One quotation inscribed on the base of the sculpture states, “Every soul is immortal.”

Plato believed the total number of souls to be immutable, with lives spent in cycles of 100 years on earth and the next 1,000 years in heaven or hell, depending on the justice and virtue of that first century lived. The first quotation on the sculpture advises caution in choosing that next soul: “Blame the one who makes the choice, God is blameless.” This quotation from The Republic reinforces the idea that the Berkeley Plato is a copy of a portrait sculpted at the time it was written, or shortly thereafter.

Tests of samples of the bust and pedestal by the Demokritos Laboratory of Archaeometry in Athens prove that both pieces are Parian marble, the stone of choice for ancient sculptors. Even more significant, Miller says, is that the Parian quarry ceased production in the late Roman period, and there is not a single example of a Renaissance or early-modern forgery or copy of an ancient statue made with marble from the island of Paros.

Heavily encrusted portions of the herm reflect its old age, as does the presence of miltos, a red pigment used in ancient inscriptions to make them more legible, he said. Unique theta and square omicron letterforms on the Berkeley Plato also are found on other ancient portrait herms, Miller says.

Additionally, the sculpture turns out to be a rare depiction of Plato not as a famous philosopher, but as a just and virtuous citizen. Paul Zanker, Sather professor at Berkeley a decade ago, has suggested that previously identified portraits of Plato were unsatisfactory because they attempted to force a prototype into the later mould of “philosopher” types.

“The Berkeley Plato,” says Miller, “not only proves that Zanker was on the right path, but it gives us a much sharper and more accurate image of Plato’s appearance. It takes us closer to that non-philosopher prototype. What a thrill to think that our contacts with the historical Plato are much more direct now than a few months ago.”

The Plato sculpture is on display at the Hearst Museum of Anthropology indefinitely. Visit newscenter.berkeley.edu to view a web slideshow of the herm.