Lifting the fog of war: chaos and lawlessness in Iraq

![]()

| 07 May 2003

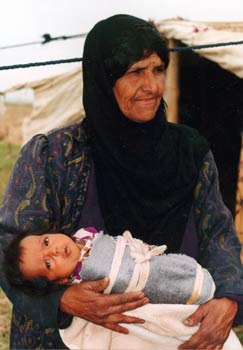

| |  A member of the Arab al-Shummar tribe, the woman at left and her family were forced out of their small village south of Kirkuk. Her evictors were Kurds who were reclaiming territory taken from them years before as part of Saddam Hussein’s “Arabization” campaign. Eric Stover photo |

While hundreds of journalists traveled with U.S.-led coalition troops, there were only two human-rights investigators in all of Iraq during the war. And as the journalists bombarded the world with reports filed seemingly every 30 seconds, these two researchers focused on one issue for days at a time, interviewing multiple people to make sure they painted an accurate picture.

“It’s very easy to write about the bang-bang of war,” says veteran human-rights researcher Eric Stover, one of the two investigators in Iraq. “It’s much harder to find out what’s actually happening on the ground and analyze it.”

But that is exactly what Stover, director of the Human Rights Center at Berkeley and an adjunct professor of public health, does. For more than two decades, working with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as Physicians for Human Rights and Human Rights Watch, Stover has immersed himself in the kind of things that make many of us turn off our televisions after a few seconds. He has waded into mass graves in Bosnia and Croatia and surveyed them in Rwanda; documented the consequences of the land mines that have claimed limbs in Cambodia and other war-torn countries; and tracked disappearances and torture in Latin America.

In March, Stover crossed the Syria-Iraq border to work as a researcher in northern Iraq for Human Rights Watch. By then, the United Nations and many other NGOs had pulled out of the country. Stover was joined by Hania Mufti, the London director of the group’s Middle East and North Africa division. Mufti, a Jordanian, speaks fluent Arabic and English and has spent two decades documenting human rights in the Middle East.

Undertaking a campaign that cried out for a legion of human rights workers, Stover and Mufti assessed the situation of displaced persons in Iraqi Kurdistan; investigated Kurdish treatment of Iraqi prisoners of war there; and, once the coalition forces succeeded in taking Kirkuk, monitored whether U.S.-led forces were obeying the Geneva Convention’s prescription to restore and ensure public order. In addition to these primary goals, Stover and Mufti also tried to ascertain the extent of civilian casualties.

Not enough tents

Before the U.S. even began its bombing campaign, several thousand Iraqis had already fled government-held areas along the border with Kurdistan for the Kurdish-controlled region, while thousands of civilians in Kurdish cities had fled to the countryside fearing chemical-weapon attacks by the Iraqi military. (Such people are called “internally displaced persons” rather than “refugees” because they have not crossed international borders.) Although the U.N. and other aid agencies had had months to anticipate the refugee flood, little had been done before they pulled out of Iraq. When Stover and Mufti arrived in Iraqi Kurdistan in mid-March, only 100 tents had been erected in a muddy camp with no sanitation facilities. Most of the displaced persons were being housed in schools and townspeoples’ homes, depending for food on what citizens shared with them. The medical facilities were woefully inadequate.

Through a Human Rights Watch press release, Stover and Mufti warned of the potential humanitarian crisis should thousands more internally displaced persons swarm across the border into Kurdistan. Fortunately, the Iraqi government did not resort to chemical weapons, and the numbers did not spike as expected.

POW protection

Turning their attention to prisoners of war, Stover and Mufti interviewed captives to find out if they were being treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Although the Kurdish forces are not signatories to the Convention, by fighting under the direction of the United States they become subject to its guidelines.

Stover and Mufti interviewed 35 Iraqi prisoners of war, access that was initially denied to journalists. “We had a very different role from journalists,” explains Stover. “They were writing a story on a different topic every day, while we would take one issue like the treatment of POWs and work it for four to five days, interviewing prisoners to find the inconsistencies and the consistencies in their accounts.”

They found that overall, the Kurdish forces were treating captured and surrendered Iraqi soldiers humanely, giving them food and medical treatment. Some Iraqi soldiers, however, were locked up with other prisoners, including suspected spies and terrorists. The Geneva Convention specifies that POWs should be housed separately for their own protection. One Iraqi officer told Stover that he was in a cell with 30 Kurds who did not speak Arabic; he was afraid to speak for the quite legitimate fear of being beaten.

“Imagine how the U.S. or Britain would feel if our soldiers were being held in cells with Iraqi criminals,” points out Stover.

Saddam’s 4-by-4-foot cells

The real challenge for Stover and Mufti came when the Kurdish forces, aided by U.S. air support and paratroopers, succeeded in breaking through the Iraqi front line in northern Iraq and retaking Kirkuk.

The two human-rights researchers accompanied the Kurdish forces into Kirkuk, a city unique in Iraq for its ethnic diversity. It is home to Kurds, Turkmen, Assyrians, and Arabs, both Muslims and Christians — a volatile mix.

Stover and Mufti interviewed Kirkuk residents and visited morgues to discover the extent of civilian casualties. They found that at least in Kirkuk, U.S. bombs had struck government and military targets with surgical accuracy, resulting in few accidental deaths.

At one of those gutted targets, Saddam’s security headquarters in Kirkuk, valuable records were strewn everywhere, whether by bombs, fleeing government officials, or looters, Stover did not know. It is the occupying forces’ duty to protect these records, he explained, to preserve what they may reveal about the whereabouts of missing persons and of crimes committed by the government.

But there were also human witnesses to such crimes. Former prisoners who had been held and tortured in the security headquarters had flocked to the bombed-out site. “They’d come back like iron filings to a magnet to see their cells,” says Stover, and they were eager to tell their stories. One man had been imprisoned with five others in a 4-by-4-foot cell for more than a year. They had barely enough room to squat on the ground, their knees and backs touching. He showed Stover and Mufti where he had scratched his name into the plaster of the now-roofless cell, a space the size of a large broom closet.

The home front

It was not the first time that Stover had been to Kirkuk. In 1991, when the city was still under Kurdish control, he led a forensic team there to exhume the graves of Kurds executed by the Iraqi government. In what is known as the Anfal Campaign of the late 1980s, tens of thousands of Kurdish civilians were forced onto trucks and driven away, never to be seen alive again. The Anfal Campaign is just a small part of the brutal history of the Kurds’ treatment under Saddam Hussein. The 1991 report that Stover co-wrote for Human Rights Watch states that “both the government of Saddam Hussein and his Baath party are responsible not only for gassing, deporting, and massacring Kurds but for destroying some 4,000 Kurdish villages.”

Now, with the fall of Saddam Hussein, Stover and Mufti feared that the 130,000 Kurds who had fled or been expelled into Iraqi Kurdistan in 1992 would return to Kirkuk to reclaim their homes. Under the Geneva Convention, forcibly displaced persons have a right to repossess their private property, but that right must be balanced against any rights the current occupants may have in domestic or international law.

“We recommended that a commission be established to oversee the gradual and orderly return of internally displaced persons to Kirkuk,” says Stover. “In the new Iraq there has to be new behavior. You can’t just go back and force people out of their homes with guns because you were forced out.”

Their fears materialized when they found four villages vacant just south of Kirkuk, on the way to Baghdad. Approximately 2,000 residents had been given official “eviction notices” by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and told to pack up and leave immediately. The residents were Arabs from the al-Shummar tribe in southern Iraq whom Saddam Hussein had moved into Kurdish homes as part of his Arabization campaign beginning in the mid-1970s. And now the Kurds wanted the territory back.

Stover and Mufti heard reports that the al-Shummar refugees had been forced from their homes at gunpoint, while their possessions were taken away. “Many of the homes we saw had been spray-painted with the names of Kurdish families,” Stover says — the families who planned to move into them.

The two investigators confronted the local PUK officials, who claimed that the resettlement policy had been approved by U.S. coalition forces. But Stover and Mufti could not confirm any such approval. “We caught them red-handed,” says Stover. “We said to them, ‘We understand your grievances, but you’re doing exactly what the Baathists and Saddam did. This isn’t right.’”

Iraq’s future

The al-Shummar residents were still homeless, camped in a fifth village, when Stover returned April 20 to the States. “It’s going to take a U.S. commander standing there with [PUK leader Jalal] Talabani and publicly announcing, ‘We will not tolerate this behavior,’” says Stover. “And that hasn’t happened yet.”

Stover reports that throughout the war, in cities across Iraq, the U.S.-led coalition failed to contain the lawlessness that arose in the vacuum left by the Iraqi government. He believes that, at least in northern Iraq, this failure was due to a shortage of U.S. troops. “We were troubled that the U.S. forces seemed to have no plan as to how they would secure Kirkuk,” says Stover. “There were guns everywhere, and so many factions. Kirkuk needs not just short-term security but long-range plans to maintain order.”

Several other Human Rights Watch representatives have arrived to take up the work in both southern and northern Iraq. Currently, Iraqis are out searching for the mass graves of missing loved ones. Stover cautions that unless the mass graves are exhumed methodically, critical information could be lost that would help to identify the bodies and preserve evidence of when and how they were killed. Likewise, if government records that bear witness to the past are to be recovered, the remains of government buildings also must be protected.

There is much to be done, and much that remains uncertain. Iraq requires not just physical reconstruction, but emotional. “What’s important now is the question of justice for past crimes, which no one is thinking of with any alacrity,” says Stover. “Will there be a Truth Commission, like in South Africa? How will Iraq deal with this past? More than 300,000 people disappeared; there was genocide and crimes against humanity.” Without the involvement of the United Nations and other international relief organization, Stover warns, Iraq’s wounds may never heal.