Dispatches from afar: Berkeley students report in from the field

![]()

23 July 2003

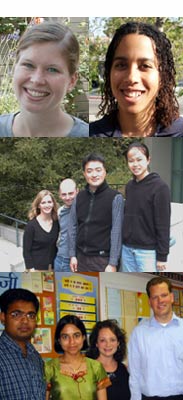

| |  Berkeley students are reporting on fieldwork around the globe this summer. They include Kristin Reed, top left, studying the oil boom in Angola, and Radha Webley, top right, looking at peace prospects in post-genocide Rwanda. Also sending dispatches are two groups of Haas School MBA students working on international projects this summer. Center photo, from left to right: Lindsay Daigle, David Hall, Toshi Okubo, and Matilde Kamiya are reporting from Borneo on the rattan trade. Bottom photo, from left to right: Amit Sinha, Mona Gavankar, Julie Earne, and David Plink filed reports from a nonprofit family-planning center in eastern India. |

Some of Berkeley’s more adventuresome students spend their summer “vacations” doing fieldwork around the globe. Their projects vary widely in focus: evaluating disparities in wealth in a resource-rich African country, family planning availability for India’s poor, the prospect of reconciliation in war-ravaged Rwanda, diplomacy at the American embassy in Paris, or the economics of rattan farming in Borneo. Luckily for us, some of these students file reports with Berkeley’s online NewsCenter, letting us share their experiences. Excerpts follow; for the full flavor of the students’ reports, visit www.berkeley.edu/news/students/2003

Angola

Kristin Reed is a Ph.D. student in environmental science, policy, and management. Her interests took her to Africa this summer, where she is studying Angola’s oil boom juxtaposed with that nation’s seemingly endless wars and profound poverty. Her postings to the NewsCenter began the day after her late-night arrival.

Waking up around noon, I found we were off to a friend’s house for lunch. It is Angolan tradition to reserve Saturdays for lunching with friends and family — and what a meal: grilled fish with sweet potatoes, sweet bananas, cassava and white beans in a palm oil sauce . . . and a generous glass of Portuguese wine. . . .

We drove back to Luanda in the thick darkness of night. The ramshackle shacks we had seen on the drive out were invisible in the shadows and the lights of downtown Luanda glittered like diamonds in the moonless night. As we climbed the stairs to the apartment, a strong wind swept a fine ochre dust through the streets, gliding between the highrises and the makeshift shelters scattered about their bases. . . .

“Não há agua hoje.” Dona Josinha tells me what I learned standing undressed in the shower moments ago, attempting to make the most of a trickle. There is no water today.

When the lights go out, you hope the generator kicks in, but there are always candles. When the water goes out, you first look to your reserves — ours is a 24-gallon garbage can in the kitchen — but when that is exhausted, a trip to the water vendors will be necessary. A majority of the poor in Angola rely on the water vendors to meet their daily needs. The costs are exorbitant. A recent Christian Aid report described the plight of a family who spent $2.75 out of their daily income of $3.50 on water. The water isn’t exactly spring water either — it often carries disease.

I carefully navigate the slick steps down to the ground floor. . . . On the street, women are ferrying heavy jerry cans of water on their heads. Some women collect water for their families by placing buckets under the eaves of the well-to-do’s apartment buildings to catch the condensation dripping from the air conditioning units. This is the way trickle-down economics works around here.

However, the streets of Luanda tell the story of both rich and poor. The gleaming towers along the waterfront and BMW SUVs contrast with the cardboard and sheet metal shelters. Street vendors sell fish, donuts, fruits, clothing, shoes, combs —whatever they can. A young man in a faded blue shirt shows me his wares: a scooter and a bathroom scale. Not far from here, in the highrise zone, multimillion-dollar contracts for oil exploration are signed. And still, with nearly one million barrels of oil produced per day, the electricity flickers off, leaving most Angolans in the dark.

Rwanda

Undergraduate peace and conflict studies student Radha Webley went to Rwanda this summer to study the effects of the genocide that took place there in 1994, leaving about 800,000 people dead in just three months. She is focusing her study on the possibility of recovery and reconciliation after such a violent period — and looking especially at the gacaca courts set up in 11,000 jurisdictions across Rwanda in the past year to bring the perpetrators to justice.

It’s Sunday afternoon here in Kigali, Rwanda, and I’m sitting on the third-floor balcony of my hotel room overlooking the street, an unpaved and potholed

reddish dirt road like so many others in this city, where pavement covers only the main highways and roads. It is late afternoon, and there is a soft haze surrounding the city, making it hard to see the terraces that criss-cross the surrounding hills.

There is a soldier in uniform standing in a doorway across the street smoking a cigarette, the same doorway where a young boy just passed by selling live roosters, grasping one in each of his hands. This street always seems to be a hubbub of activity.

At night, this street explodes with music and voices. Last night there was a man playing guitar and singing on the porch across the street, with a small crowd gathered around him. Mornings are also a busy time on this street, with lots of traffic and horns honking and building construction underway somewhere nearby. Needless to say, the noise makes it a pretty hard place to sleep. ...

Someone I was talking to at the church pointed out that whenever foreigners think about Rwanda, they think only of war and genocide and forget the rest, and that has certainly been my experience in studying and reading about Rwanda. So it is refreshing to be here and to see the other aspects of Rwanda, the parts of the country that give Rwanda the complex human face that no written account of a country can possibly portray.

Someone [else] told me last week that the foundation of the gacaca courts lies in Rwandan culture, that in this culture there exists a moral obligation to forgive others for crimes suffered, and that it is upon that basis, and only upon that basis, that the courts will be able to function, will be able to fulfill their reconciliatory purpose. A few nights later, someone else exclaimed, “Forgiveness is not possible in Rwanda! How can anybody who has had 30 members of their family killed possibly be expected to forgive their killer? How is that possible? It is not! Forgiveness and reconciliation is not a reality here. People must go on with their lives, they have no choice. But forgiveness? Not here, not in my lifetime!”

India

Haas School MBA students Amit Sinha, David Plink, Julie Earne, and Mona Gavankar are in Bihar in eastern India this summer to help Janani, a nonprofit family-planning agency, improve and broaden its services in rural areas. Bihar is a good site for their work because of its poverty, high fertility and low literacy rates, and very low prevalence of contraceptive use. The students are analyzing Janani’s efforts to increase the number of Surya clinics in Bihar that provide affordable family-planning tools and services to the poor.

Government health services are scarce in Bihar. After visiting one of the government clinics we decided that maybe that is for the better: An absolute lack of hygiene and available services make these the most atrocious places to receive health care. We saw the operating theater, a dark room where the available equipment consisted of a wobbly table and used syringes lying all over the place. The services at these clinics are usually free and are aimed at the poorest of the poorest.

Janani’s 500 Surya clinics — the focal point of our research — aim at the clients who are willing and able to pay a small amount for reproductive-health-care services. As franchisees in the Janani network, these clinics benefit from cheap products, a strong brand value, and joint advertising (Janani is the largest radio advertiser in the state of Bihar). ...

[W]e asked doctors and patients about new services they would like to see provided. Based on our findings, we have identified childhood vaccinations as the most promising target and are modeling this possibility.

There is, however, a huge complication in offering immunizations: transporting them. Most vaccines must be kept refrigerated at all times, and the polio vaccine even has to be kept below -20 degrees Celsius (-4 degrees Fahrenheit) or else it loses its effect. The Indian government has issued a set of guidelines, called the Cold Chain, on how to transport and store the vaccines properly. These transportation requirements affected our analysis hugely. Most of the Franchised Surya Clinics, which are run by small family businesses, do not have access to electricity at all times, so storage of the vaccines is a problem. We had to come up with a solution for this issue or the immunization project was doomed to fail before it even started.

Borneo

Haas MBA students Lindsay Daigle, David Hall, Matilde Kamiya, and Toshi Okubo are filing regular dispatches this summer from Borneo, where they are consulting with a farmers’ consortium that is trying to turn the region’s traditional rattan cultivation into a profitable and sustainable business. The hope is that by keeping more of the earnings from rattan sales at the farmers’ level, there will be less incentive to clear-cut the forests in which the rattan grows.

The Indonesian morning begins early. The sun rises around 5 a.m., and about the same time, you can hear the call to prayer in the distance. As Dave and Lindsay hadn’t arrived yet, Toshi and Matilde decided to explore the city of Samarinda. We stopped by the hotel lobby and asked for directions downtown. The lady responded, “Here is downtown.”

After a “late” breakfast at 8:30 (people in Samarinda typically get up at 5 a.m.), we met our client Ade to go over the business plan. Ade works for the Consortium for Community-based Forest Management East Kalimantan, a non-governmental organization committed to the environment that gets involved in all sorts of projects to save the Indonesian forest. To this end, [the consortium] has identified rattan farming as a sustainable source of income for the people in East Kalimantan. Rattan is a bamboo-like climbing plant that grows on forest trees. If farmers grow rattan, they won’t cut down the forest to make money on timber. However, the price for rattan is low, and continues to face pressure from the extremely long supply chain the farmers must go through to get their rattan to the end customer (the rattan-furniture buyer in Jakarta). Our friend Ade has written a business plan to create a company that will take the farmers’ rattan, pool it, and sell it to the furniture manufacturers, thereby vertically integrating many disjointed functions into one company. He hopes this will allow this company, called SEP, to offer farmers a high-enough price to keep them from cutting down the forest.