How and when to bring the Hubble home

![]()

| 27 August 2003

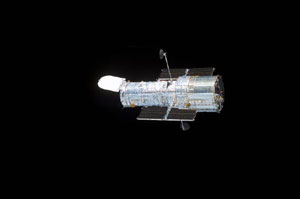

| |  Berkeley experts say there’s plenty of work for the Hubble Space Telescope yet to do — if NASA approves its continued operation. Image courtesy NASA |

Two Berkeley physicists recently joined colleagues on a NASA advisory panel in unanimously recommending that NASA extend the life of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) to maximize the amount of science it does before plummeting to Earth.

“We are urging them to keep it going as long as practical,” says Nobel Laureate, physicist, and panel member Charles Townes, a Professor in the Graduate School at Berkeley.

Fellow panel member Christopher McKee, chair of Berkeley’s physics department, says the panel’s recommendations reflect the consensus of the astronomical community, but must be weighed against other new space astrophysics proposals.

“The Hubble Space Telescope has revolutionized astronomy, and will continue to do great astronomy,” McKee says. “But NASA must take many factors into account in addition to science in reaching a final decision about the telescope.”

The six-member panel, formed in January to advise NASA on the future of the HST, issued its final report earlier this month, providing the agency with three preferred options, depending on the ultimate fate of the shuttle fleet.

NASA originally planned to service the telescope for the fourth time in about 2005, then send up a fifth shuttle mission around 2010 to bundle up the telescope and haul it back to Earth. This would provide a nice museum exhibit and remove the admittedly small risk of injury should the telescope plummet to Earth.

The February disintegration of the Columbia shuttle, however, threw a wrench into these plans, promising fewer shuttle flights and making NASA less willing to risk astronauts’ lives to bring the telescope home.

Astronauts’ zeal for risk is science-dependent

Says McKee: “Astronaut John Grunsfeld addressed the panel and says that he and his colleagues realize that whenever they go up they are risking their lives, and they are perfectly willing to do that in order to enable Hubble to do more science, but they were not ready to risk their lives just to bring it back to stick in a museum.”

NASA has proposed strapping a rocket to the butt of the telescope to guide it safely through the atmosphere to a mid-ocean plunge, but it’s unclear whether a shuttle trip will be required to do this or if it can be performed by an unmanned robotic mission.

“Right now, there is no propulsion module that can be taken up in a shuttle, and it’s possible that, after review, that may be regarded as too dangerous,” McKee says. “Then you would have to go to a robotic propulsion module that would latch onto the shuttle and bring it down, but such a module does not exist, either.”

The panel, chaired by John Bahcall of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., argued to keep Hubble aloft because it can contribute great science for another decade or more and it complements its successor, the planned James Webb Telescope. Hubble provides great images in the visible and ultraviolet wavelength bands, while the Webb telescope will be optimized for infrared observations to probe the heart of dust clouds and the red-shifted light from the earliest days of the universe.

“The James Webb Telescope is going to provide a much greater leap in our capabilities than Hubble will, offering the potential for making new revolutionary discoveries,” McKee says. “But you still have the option of putting new instruments on Hubble, making it even more powerful than it is now.”

The Hubble Space Telescope has been a boon to astronomers since it first started snapping pictures of the heavens in 1993. Since then, the public has feasted on colorful photos of dust clouds, startlingly sharp pictures of distant galaxies, and hauntingly deep images showing the wealth of galaxies in the universe. These images have had a major scientific impact in nearly all areas of astronomy.

“One of the most important discoveries in the physical sciences in recent years was the discovery of acceleration of the universe,” McKee says. “That was done with ground-based telescopes, but observations with Hubble were crucial in helping to both establish that result and show that the acceleration hypothesis was the correct explanation of the data.”

“By any standards the HST has been a spectacular success — one of the most remarkable facilities in the entire history of science,” the panel’s report concluded.