Berkeleyan

Farewell to a marvelous idea?

![]()

| 28 January 2004

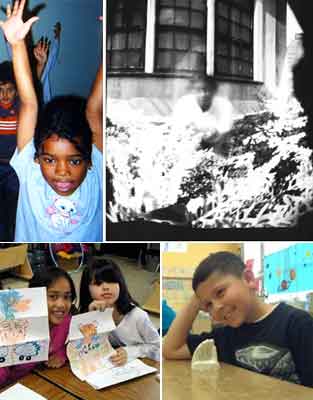

| |  ArtsBridge images from Spring 2003 (except where noted), clockwise from upper left: Second-grade students participate in a modern-dance project at Oxford School in Spring 2002. (ArtsBridge Scholar: Lily Dwyer; Host Teacher: Cathy Jones) A photo produced with a pinhole camera by fifth-grade students at Stonehurst Elementary School. (ArtsBridge Scholar: Kate Tomlin; Host Teacher: Steffie Spanakos) Jefferson Elementary School students have their creativity tapped with an art project. (ArtsBridge Scholar: Kiram Nigan; Host Teacher: Christine Hollander) A third-grade student at Allendale Elementary School proudly shows off a plaster casting of his hand. (ArtsBridge Scholar: Cheryl Wong; Host Teacher: Nuria Cezón Ruiz) Photos courtesy of Consortium for the Arts |

If the governor’s proposal to cut all state funding for UC outreach programs is approved, one of the affected programs will be ArtsBridge, which connects UC students in the arts with K-12 public-school teachers who want to provide their students with hands-on arts instruction.

Each ArtsBridge Scholar is given a $1,250 scholarship to lead a semester-long arts workshop in a single K-12 classroom, under the guidance of a UC Berkeley faculty mentor and in collaboration with the regular classroom teacher. Priority is given to sending Scholars to schools ranked as underperforming, or that suffer from minimal arts resources.

At its peak, more than 50 student-artists participated in the program, which was recognized by Chancellor Berdahl as an outstanding University-Community Partnership in 2000. They have taught fourth graders about poetry and world dance, or tenth graders about photography and digital art.

“These students have an artistic gift that they’ve had the opportunity to develop here at Berkeley,” says Art Practice lecturer Craig Nagasawa, who has administered the program from its inception. “They want to use their talent to give back to the community in some way.”

The Consortium for the Arts, which provides a home for the program at UC Berkeley, has had some success in raising private funds to supplement state funding for ArtsBridge. But the consortium does not have the resources to cover the 90-percent cut in state funding that the program has already suffered, let alone the proposed 100-percent cut.

So it seems likely the program will die, despite the fact that it has been universally praised, that under Nagasawa’s direction it has established an elaborate network of connections in school districts throughout the East Bay, and — perhaps most objectionably — that those killing it probably know nothing about it. They know only that K-12 students and their teachers have little political clout — and that what clout they do have has to be marshaled for issues like salary and class size.

They cannot have known the smile on an individual teacher’s face when a student helper arrives with fresh ideas, and with faith in their students’ abilities to take on new challenges.

They cannot have sensed the excitement of the students themselves as these new teachers focus attention just on them — to help them learn that art is fundamentally the enjoyment of a skill that makes possible inventive ways of engaging in social interactions.

They cannot have felt what it means for students mired in a culture of failure to succeed at mastering a skill like dance or drawing, and coming to appreciate the pleasure of learning that so many of us take for granted.

Above all, they cannot have an inkling of what it means for today’s students, brought up in a culture of narcissism, to recognize what good they can accomplish by sharing the skills the university has helped develop.

Or could they know and not care? Could they know what programs like this accomplish, yet prefer to save the pennies that they exact from the taxes that fund such programs? Could they know and not care that virtually every student who has been through this program ranks it as one of the highlights of his or her education at Berkeley? And could they know and not care that two or three students every semester decide, on the strength of their ArbsBridge experience, that they will try K-12 teaching when they graduate?

For the first time in my 35 years in university teaching I prefer ignorance as an explanation for such behavior. The hypothesis that the state’s budget-makers could knowingly choose such callousness makes me worry that this is only the beginning of the dismantling of public education.

Charles Altieri, Stageberg Professor of English, directs the UC Berkeley Consortium for the Arts, www.bampfa.berkeley.edu/bca/.