Berkeleyan

It’s cold out there, say foreign students and scholars

Berkeley survey documents post-9/11 visa troubles, ‘chilly’ climate —and may help explain a nationwide decline in applications from abroad

![]()

| 28 April 2004

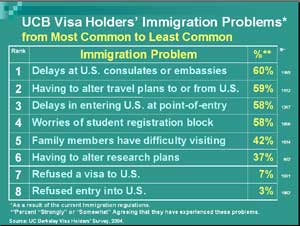

| |  Campus visa holders, in response to a recent survey, reported a variety of problems related to current U.S. immigration rules. The most common problem — which often complicates a foreign student’s academic plans — has been delays in securing a visa from a U.S. embassies or consulates back home. UC Berkeley Visa Holders’ Study, 2004 |

Immigration problems are a source of frustration and concern for international students, scholars, and faculty from every world region, according to a recent survey of U.S.-visa holders at Berkeley. Nearly 60 percent reported delays at U.S. consulates or embassies in their home countries. Close to 60 percent, as well, said they had had to alter travel plans to or from the United States. About the same percentage have worried that, because of bureaucratic delays and complications, they would be prevented from registering for their classes — which can lead to deportation.

“Random, long (from a few weeks to a few months, even a year) security checks … is a HUGE pain for Chinese students!!” wrote one respondent.

“I share the feeling of all postdocs that I know,” said another, from France. “We are afraid to travel in our country of citizenship for family reason or for interview, because we are afraid to experience very long delays for re-entering the U.S.”

Telling their story

The Berkeley survey captures the experiences of 1,688 U.S. visa holders — 307 undergraduates, 903 graduate students, and 478 visiting scholars, faculty, and postdocs. It is one of the first, if not the first study in the nation to poll individual students and scholars on the impact of post-Sept. 11 immigration policies, says Mary Ann Mason, dean of the Graduate Division — which conducted the survey between Feb. 25 and March 24. The division e-mailed 3,275 visa holders on campus; 52 percent completed the questionnaire. “They wanted to tell their story,” Mason says of the high response rate.

More than four out of ten of the U.S.-visa holders responding reported that family members have had difficulty visiting them in the United States. “My parents cannot get their visa to visit me and see their newborn [grand]child,” said one Berkeley student from China. “I am suspicious whether they can get a visa for my commencement this May.” Another 37 percent said they had had to alter research plans as a result of current immigration policies; in the sciences, technology, engineering, and math, this was true for more than 45 percent of respondents.

Not surprisingly, more than two-thirds of students and scholars from Middle Eastern countries reported delays at an airport or other point of entry related to their immigration status. So did more than half of all respondents. Among those reporting the fewest point-of-entry problems — citizens of India, Bangladesh, Australia, or New Zealand — nearly one in two experienced delays.

New immigration procedures

The problems documented by the survey reflect a series of changes to immigration policies and procedures since Sept. 11, 2001, says Ivor Emmanuel, director of Services for International Students and Scholars (SISS), based at International House. As of last August, for example, his office has been required to track international students and scholars using the new federal Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS). American embassies and consulates abroad have been directed to interview virtually every visa seeker in person, without the resources to do so in a timely manner. And dozens of fields of study, from nuclear engineering to environmental design, now appear on a list of “sensitive technologies.” If a student or scholar plans to study any of these fields, his or her file is sent to Washington, D.C,. for a closer “Visas Mantis” review — and typically months of additional delays.

Emmanuel notes that as new immigration policies have been introduced, each has served “to add a new obstacle or barrier,” and each new barrier has made it harder for international students and scholars to register for and begin classes on time, leave the country to attend a scholarly conference, or return home for personal reasons without fear of being denied a reentry visa.

Looking elsewhere?

The U.S. currently hosts some 60,000 international students and scholars a year — among them brilliant minds like those who, in the past, have remained in the U.S. after graduation to drive innovations in science, engineering, and technology. These foreign students also contribute more than $12.8 billion to U.S. educational institutions and the domestic economy, according to a recent estimate by the National Association of Inter-national Educators.

But will talented international students continue to apply to U.S. institutions, despite the kinds of immigration problems they now face, or will they begin to look elsewhere for educational opportunities, as one respondent to the visa-holder’s survey suggested? “I am sure that more and more researchers, myself included, will try to find more hospitable environments outside the U.S. in the future,” a student from Switzerland commented.

Studies by major educational organizations, in fact, document significant drops in international-student applications. One, by the Washington-based Council of Graduate Schools, found a 32-percent decline in international-student applications to U.S. graduate schools for fall 2004. At Berkeley, foreign students’ application rate to graduate school declined by 22 percent (the largest decline being in applications from China, a drop of 43 percent). If the overall decline is an anomaly, notes Mason, “one year is not going to make a difference. If it’s a trend, it’s very threatening to us.”

Recommendations pending

Mason says that the campuswide Task Force on International Students and Scholars, which she chairs, is formulating recommendations — based on the visa-holders’ survey and other input — of measures designed to improve the climate for international students and scholars and assist them in navigating the immigration system. “We want the international members of our community to know,” she says, “that Berkeley welcomes and supports their contributions to the excellence of our university.”