Berkeleyan

Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz dies

![]()

| 18 August 2004

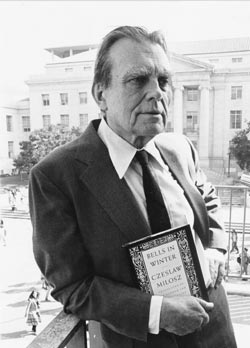

| |  On Oct. 9, 1980, Berkeley professor Czeslaw Milosz, then 69, spent much of the day before camera lenses, as the press descended on the campus to photograph the newly announced winner of the Nobel Prize for literature. (Saxon Donnelly photo) |

Czeslaw Milosz, the Polish poet, Nobel laureate, and Berkeley professor emeritus, passed away Saturday, August 14, at his home in Krakow, Poland. He was 93.

He died surrounded by his family, the Associated Press reported; the cause of death was not immediately known.

“He was one of the towering poets of the 20th century,” says Robert Hass, professor of English and former U.S. Poet Laureate. Hass was a friend and the primary English translator of Milosz’s complex and powerful works written in classical Polish; over a period of 20 years they had met nearly every Monday morning, working together to translate Milosz’s poems.

In 1980, Milosz was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature — the campus’s first and, to date, only Nobel in the humanities. The prize coincided with the emergence of the Solidarity worker protest movement that helped bring about the end of Communist rule in Poland.

The Swedish Academy of Letters, in its commendation, described Milosz as a writer of “uncompromising clear-sightedness who voices man’s exposed condition in a world of severe conflicts.”

Revered teacher

When Milosz received the Nobel Prize, he had been teaching in Berkeley’s Department of Slavic Languages and Literature for 20 years. He retired as a professor in 1978, at the age of 67, but continued to teach classes; on the day of the Nobel announcement he cut short the celebration to attend to his undergraduate course on Dostoevsky. The choice was characteristic of Milosz, who accepted his fame with some reluctance, saying he’d be “happy to go on in solitude writing poems in an exotic language,” and whose stature as a teacher was towering.

“I have only great, good, and majestic things to say about the professor and his lectures,” a typical class evaluation by one of Milosz’s students read.

Milosz had been lured to the campus in 1960 by Frank Whitfield, then chair of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature. “He had never taught a day in his life,” Hass says. But his prose work Captive Mind, published in 1956, had brought him international renown. It was written, at least in part, to explain his defection from communist Poland, whose government he had served as a diplomat.

“People understood that he was the most important Polish writer then writing and he was in dire straits,” says Hass. He had been granted political asylum by the French and was living in Paris, “trying to support himself, his wife, and their two sons through freelance writing,” which was banned in Poland. Offered a position as lecturer at Berkeley and Indiana, he chose the former — in part, he writes in Milosz’s ABC’s (2001), because he thought it was situated on a sandy beach.

Milosz was supposed to teach the history of Polish literature, Hass said, but there was no textbook about the subject in English. So he hired a secretary “and dictated in English the history of Polish literature over the course of one summer.”

Although he found the Bay Area’s natural environment alien, his position on the Berkeley faculty suited Milosz in important ways. “It is much more healthy for a creative writer to have a job and honestly earn one’s living instead of catering to the needs of the market,” he once said. The campus offered other advantages as well. In Conversations With Czeslaw Milosz the poet referred, for instance, to the rich trove of primary-source materials he unearthed in UC Berkeley libraries and made use of in his poetry — Lithuanian encyclopedias, his personal family tree, even German ordnance maps on which the house where he was born was marked.

Lithuania to Grizzly Peak

Milosz was born in Lithuania in 1911, then under the domination of the Russian tsar. His childhood, spent partly in Russia just before and after the Revolution, is described in his novel The Valley of Issa, published in 1955, and in his autobiography, Native Realm (1968).

Following the war, the family returned to Lithuania, where Milosz studied law at the University in Vilnius. He spent most of World War II in Nazi-occupied Warsaw, where he worked as a janitor in the Warsaw University library, published poetry in anti-Nazi underground presses, and witnessed the destruction of the walled Jewish ghetto.

A documentary on his life for public television, Czeslaw Milosz: The Poet Remembers, speaks of his sense of guilt, as a Christian, for events that transpired there. Milosz grappled with the experience in such poems as “A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto” and “A Song on the End of the World.” In retirement, he learned Hebrew (one of many languages he mastered) in order to translate the Old Testament into Polish, and worked to promote the dissemination of Jewish literature in that country.

In Berkeley, he lived in a house on Grizzly Peak Blvd. — from which the Polish exile looked out over the “spectacular but lunar” land- and bayscape spread out beneath him and, as Hass once put it, “tried ferociously to make sense, in increasingly powerful art, of what it’s been like to be alive in this century.”

When the Iron Curtain fell, Milosz was able to return to Poland — this time to a hero’s welcome — “although ‘heroic’ was a mantle he shunned,” literature professor Robert Faggen, of Claremont McKenna College, told the Washington Post. “At the monument in Gdansk [birthplace of Solidarity] you have icons of three figures: Lech Walesa, Pope John Paul II, and Milosz.”

Until the last few years, he and his second wife, Carol, split their time between their apartment in Krakow and their home in Berkeley.

Milosz offered his last campus reading, in Polish and English, in February 2000, at age 89, to an overflow crowd in the Library’s Morrison Reading Room. “He went back over his whole career, reading many of its highlights, for close to an hour,” recalls Zack Rogow, coordinator of the Lunch Poems series, of which the reading was a part. “I had the feeling I was reliving some of the literary peaks of the 20th century. “

Of cats and catastrophes

In that event, Milosz read poems about cats and Winnie the Pooh characters as well as about the human catastrophes to which he had been witness. One piece, “To Wash,” read as follows: “At the end of his life a poet thinks: I have been plunging into so many of the obsessions and stupid ideas of my epoch! It would be necessary to put me in a bathtub and to scrub me till all that dirt was washed away. And yet only because of that dirt could I be a poet of the 20th century, and perhaps the Good Lord wanted it, so that I was of use to him.”

Milosz is survived by his two sons. His first wife, Janina, died in 1986. His second wife, Carol, a U.S.-born historian, died in 2003. Funeral arrangements for Milosz are pending.