Berkeleyan

Smallest-yet planets found around nearby stars

Astronomers push limits of detection methods to identify planets barely a dozen times the size of Earth

![]()

| 02 September 2004

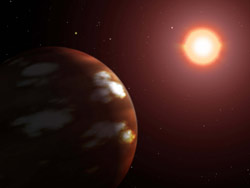

This artist's concept shows a newfound Neptune-size planet circling the star 55 Cancri. The planet’s temperature is at least 1,500 degrees Celsius. Though depicted as rocky, it may be gaseous: astronomers don’t really know. (Image courtesty NASA) |

“It sounds a bit strange, but we’re not thinking in terms of Jupiter masses or Saturn masses anymore, but Earth masses,” said Geoff Marcy, a professor of astronomy at Berkeley and a member of one of two teams reporting the discoveries. Neptune is 17 times more massive than Earth, while Saturn and Jupiter are 95 and 318 times larger, respectively.

“All exoplanets found so far are almost certainly gas giants, but these new ones are a puzzle — they could be gaseous like Jupiter, but they also could have a rock-ice core and a thick envelope of hydrogen and helium gas, like Neptune, or they could be a combination of rock and ice, like Mercury.”

Marcy and planet-hunting colleague Paul Butler of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, along with Barbara McArthur of the University of Texas, leader of the second team, announced their finds during a media briefing broadcast live on NASA TV on August 31. Two papers detailing the discoveries were submitted to The Astrophysical Journal in July and accepted earlier this month. The paper by Butler, Marcy and their colleagues will appear in the Dec. 10 issue, while that of McArthur and her colleagues has not yet been scheduled for publication.

The detection of a third Neptune-size extrasolar planet, not yet peer-reviewed, was announced by European astronomers on August 25, just a few days after its discovery. All three of these planets were discovered by tracking the wobble caused by each planet tugging on its parent star, which produces a Doppler shift in the light emitted by the star.

The new planets, though approaching the Earth in size, are still far from Earth-like. Both whip around their stars in a few days and are so close as to be roasting on the side facing the star. Because each planet is so close to its star, its rotation is no doubt locked into its orbital period, so that it always presents the same face to the star, Marcy said.

The smaller of the two planets, with a minimum mass of 14 Earth masses, was discovered by McArthur and her team around the star 55 Cancri (or rho-Cancri). It is the fourth planet found around 55 Cancri, a yellow G star not unlike the sun, located only 41 light years from Earth in the constellation Cancer. (A light year is 6 trillion miles.) The star is the first four-planet system discovered, and “the closest analog we have to our own solar system,” McArthur said.

The larger planet, with a minimum size 21 times the mass of the Earth, orbits a red M star, Gliese 436, which is about 50 times dimmer than our sun and located 33 light years away in the constellation Leo. This planet is only the second discovered around an M dwarf, the most common type of star in the galaxy.

If the planet orbiting Gliese 436 has little atmosphere to spread the heat around, it is likely to have temperatures of 377 Celsius on the side facing the star, where it would be perpetual noon, and a frigid tens of degrees above absolute zero where it’s perpetual midnight. However, temperatures on the twilit border could be more comfortable, at least from an Earthling’s perspective, Marcy said.

“The front is hot and the backside is probably cold, but the region in between could have moderate temperatures between 0 and 100 degrees Celsius,” he said.

Temperatures on the planet orbiting 55 Cancri are at least a scorching 1,500 Celsius (2,700 Fahrenheit) because of its proximity to the star, McArthur said.

Following the wobbles

The near simultaneous discovery of these smallest-yet planets indicates they could be common, Marcy said.

“If you look at the 135 or so extrasolar planets found so far, it’s clear that nature makes more of the smaller planets than the larger ones,” he said. “We’ve found more Saturn-size planets than Jupiter-size planets, and now it appears there are more Neptune-size planets than Saturn-size. That means there’s an even better chance of finding Earths, and maybe more of them than all the other planets we’ve found so far.”

In a galaxy like the Milky Way, which has some 200 billion stars, 20 billion might have planets with masses between 10 and 20 Earth masses, he said.

Butler, Marcy, and colleagues Debra Fischer, of UC Berkeley and San Francisco State University, and Steve Vogt, professor of astronomy at UC Santa Cruz, discovered the planet around Gliese 436 last year after four years of observation on the Keck I telescope in Hawaii. They have been observing the Doppler shifts of 950 nearby stars, 150 of them very nearby, low-mass stars called M dwarfs, which comprise 70 percent of all stars in the galaxy. All the M dwarfs are within 30 light years of Earth.

After following the star’s wobbles for another year, the team concluded that Gliese 436 has a Neptune-size planet of at least 21 Earth masses, though more likely 25 Earth masses, that zips around in a circular orbit once every 2.64 days. That corresponds to an orbital radius of roughly 2.8 million miles (4.5 million kilometers), or about 3 percent of Earth’s distance from the sun. In our own solar system, Mercury, the closest planet to the sun, orbits in 116 days at a distance of 37 million miles (58 million kilometers).

McArthur and her colleagues in Austin discovered the smaller planet after analyzing data on the wobbling of 55 Cancri obtained with the 9.2-meter Hobby-Eberly telescope of the McDonald Observatory, in combination with data from the Marcy-Butler-Fischer-Vogt team, which had earlier discovered three planets around the star. They also used data from a rival planet-hunting team directed by Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Diedre Queloz.

Once they obtained the data from previous years, McArthur’s team organized a major campaign to study the 55 Cancri system and took another 100 Doppler measurements over the course of 190 days.

The new data revealed that the star has a fourth planet with a minimum mass of 14 Earth masses, an orbital period of 2.81 days, and an orbital radius of just 3.8 percent that of Earth. Because the orbit of the planet is tipped relative to our line of sight, the most likely mass for this planet is 18 times that of Earth, based on astrometry conducted with the Hubble Space Telescope.

Marcy predicts that more and more Neptune-size planets will be discovered in the near future, thanks to a new CCD digital camera being installed on the Keck telescopes’ spectrometer in Hawaii. Built by Vogt and his UCSC team, it will allow detection of smaller stellar wobbles, around 1 meter per second, compared to today’s best resolution of 3 meters per second. The planet around Gliese 436 caused it to wobble about 18 meters per second. Since most of these planets would be in close orbits around the star and with very short orbital periods, a few days of observation could yield several sub-Neptune planets, he predicted.

“This is a real breakthrough,” Marcy said. “We should be able to easily detect planets only 10 times the Earth’s mass. I expect we’ll find dozens of planets between 10 and 20 Earth masses in the next few years.”