Berkeleyan

Bringing sociology home

Striving to engage the public is a tradition among Berkeley sociologists. A critical study focusing on the campus’s lowest-paid workers is squarely in that tradition, its authors say

![]()

| 30 September 2004

Though it doesn't read much like a standard academic treatise, this slim study exemplifies a Berkeley sociology tradition. |

Sociologists travel far and wide to observe our collective existence as a species and send home news. From the pens of sociological writers come dense scholarly articles, best-selling books, and New Yorker exposés on factories and families; life in gangs, suburbia, prisons, corporations, classrooms; the industries surrounding birth and death.

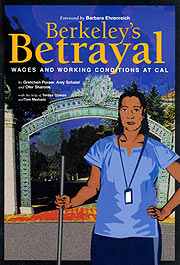

Yet practitioners of this wide-ranging social science sometimes choose to ply their trade close to home — as did a group of Berkeley grad students with a strong activist bent who set out to study the situation of the lowest-paid employees on the Berkeley campus: food-service workers, custodians, groundskeepers, and clerical workers, among others. Earlier this month they released their findings in a 34-page study titled “Berkeley’s Betrayal: Wages and Working Conditions at Cal.” With extensive quotes from 63 workers interviewed during the 2001-02 academic year, it paints a critical picture of wages earned and working conditions experienced by those at the bottom of the campus compensation scale. (The report is online at www.berkeleysbetrayal.org.)

The authors of “Berkeley’s Betrayal” — Gretchen Purser, Amy Schalet, and Ofer Sharone — align themselves with the intellectual trend within their discipline known familiarly as “public sociology,” which they characterize as “sociological research that seeks to open up public dialogue about the pressing issues of our time,” and which has numerous advocates within the department at Berkeley. On its surface the report doesn’t look very much like conventional sociological scholarship: It begins with a strongly worded foreword by social critic Barbara Ehrenreich, who mentored the authors early in their project, and concludes with a 10-point action plan based on the findings: a call to Chancellor Robert Birgeneau to take such steps as instituting a living wage, guaranteeing parking and transportation, and holding supervisors accountable for their actions. The body of the report, meanwhile, eschews a dense methodology section or adherence to sociological theories of workplace organization or class stratification. Instead, it relies heavily on quotes from 63 workers interviewed for the project, citations from the Daily Californian and Berkeley Daily Planet, messages from former Chancellor Robert Berdahl, and data from surveys conducted by the campus.

All of this is by design, say the authors — who purposely avoided many conventions of scholarly writing in order to produce a report accessible and compelling to a non-academic audience. In this, they believe, they’ve succeeded. “One of the most gratifying things to us,” says Sharone, “is how many workers have read the report. It’s a sign that we’ve reached beyond the usual academic audience.”

Believing in UC’s mission

In addition to complaints about low wages, difficult parking, insufficient staffing (and related overwork), and various health and safety issues, many interviewees raised issues of dignity and respect in the workplace. Despite their predisposition to sympathize with the various challenges those employees face, the study’s co-authors found workers’ emphasis on this repeated theme, in the course of open-ended interviews, something of a surprise. (“[S]eemingly minor indignities caused workers as much anguish as did the ‘major’ injuries of insufficient incomes and unhealthy working conditions,” they observed.)

“The workers taught us that sweeping is not just sweeping,” Sharone told a campus audience at a Sept. 14 presentation on the report’s findings. “They’re attracted to work at the university for the very same reason that many faculty choose to work at a university — a belief in the institutional mission.” This desire, Sharone said, “sets them up for deep and painful disappointment if their contribution is overlooked or their full membership in the university community is denied.”

Many of those quoted in the study talked about workplace practices that they experienced as neither fair nor consistent. “Being passed over for a promotion can color everything,” notes Sharone. “After not getting a promotion, the little things” — like not being thanked, or not receiving campus communications available to those with e-mail — “hurt more.”

In the conclusion to their report, the authors state that “the actual wages and working conditions at the university violate the very principles that it seeks to claim as its own.” Berkeley is not alone in this, they say: Universities nationwide “have succumbed to the seduction of the for-profit sector’s relentless celebration of the bottom line,” joining corporations “in disregarding the humanity and basic needs of workers at the bottom of the income distribution.”

| Looking at the total package |

| Workers quoted in “Berkeley’s Betrayal” relate strategies — many of them ad hoc and not entirely successful — for surviving on low wages that have not kept up with the rising cost of Bay Area living. (The authors cite a California Budget Project calculation pegging $16.88 per hour as the minimum salary each parent in a two-income family needs to support a family of four, and then cite UC wage data to show that close to 1,700 campus workers make less than that.) While acknowledging UC’s generous healthcare benefits, they claim that the university’s “commitment to health does not extend to ensuring a safe and healthy work environment.” Instead, they say that “across job classifications and departments, workers described being denied even the most basic injury preventative equipment.” On the subject of health and safety, Steve Lustig, acting vice chancellor for Business and Administrative Services, cites Berkeley’s strong programs to reduce work-related illness and injury. He invites the authors to learn more about them, saying “I’m thrilled at students’ involvement in learning about staff and how hard they work to support the university’s mission.” With regard to salary issues, Lustig, says that the head of Human Resources, David Moers, is planning to meet with the study’s authors to go over the figures it presents and to review work that is being done to address salary levels. “You have to look at the total package,” he says, “and compare that to other total packages — benefits, vacation and sick leave, and hourly salary — in order to make progress in this area.” Lustig notes that the campus is aware of, and working on, many issues raised in the report. For example, staff have talked about salary, career growth, and working conditions (particularly relationships with their supervisors) in exit and entrance surveys. “Some of the issues raised [by the report] can be addressed on the campus level, some need to be addressed on the systemwide level,” he says. About 70 percent of Berkeley staffers are covered by contracts (14 in all) with UC; salary ranges are set systemwide, with some leeway for adjustment on the campus level, depending on the contract. Ongoing discussions about working conditions have led to development of new training materials for faculty and staff supervisors, says Lustig, “and a lot of that has been rolled out this semester.” The administration has developed other programs and policies — like the CDOP career-development program, work-life policies, and a new matching fund for ergonomic-equipment purchase — to improve working conditions on campus. Says Lustig: “We look forward as a community to working on these issues of common concern, especially staff support and working conditions.” |

Making institutions accountable

The desire to reach a broader segment of the public, felt by many scholars across the disciplines, has played a role in the field of sociology since its beginnings and has a strong tradition in the campus’s sociology depart-ment, now just a little over 50 years old.

“The Berkeley department has always been interested in contributing to stimulating public debate,” says departmental chair Kim Voss. “So in that sense ‘Berkeley’s Betrayal’ is part of a tradition.” One goal of public sociology, she notes, “is to give voice to constituencies that generally don’t get heard from in public debate. In that sense, this study was great.”

Professor Michael Burawoy, Voss’ predecessor as department chair, likewise praised the report as a fine example of public sociology, which he defines as sociology that strives to engage different publics and then to make institutions accountable to publics. By his account, the Berkeley campus is an “epicenter” of this kind of social science. “There’s a culture [here] that supports doing this sort of work,” Burawoy says. “You won’t be denied a promotion just because you wrote a book that someone can read outside the academy.”

During his four years as chair of the department, Burawoy collaborated on a history of sociology at Berkeley, where the formal creation of a department came late, relative to other social sciences on campus and to other major American sociology departments. By his account the Berkeley department has been a major force in postwar American sociology: In the late 1950s it became a top-ranked home of “professional sociology” (his term for sociological research and writing in the academic context), and for much of the period since it has been a leading center of “public sociology.” (Not all departmental faculty subscribe to this account; “public sociology,” for some, is just a new name for longstanding currents within the field, and its place at Berkeley is misrepresented by this telling.)

As 2003-04 president of the American Sociological Association, Burawoy was an outspoken and dogged spokesperson for public sociology. He crisscrossed the nation to speak on its behalf at state universities and professional organizations. Then he made it the central theme of this year’s annual ASA meeting in San Francisco, which featured scores of thematic sessions on public sociology, as well as prominent public intellectuals from abroad. “I wanted American sociologists to see that public sociology is the essence of sociology in many countries,” Burawoy says.

“Berkeley’s Betrayal” was first presented in a thematic session at that meeting. By Burawoy’s lights, the “beautifully written” report is squarely in the tradition of the renowned French sociologist Emile Durkheim (1857-1917), who, he says, “wrote about a division of labor in which people doing different things should recognize each other and feel part of a common community.” A lot of the report is about the “forced invisibility” experienced by low-paid workers, “who want to be part of a community from which they feel excluded. That’s a very Durkheimian analysis.”