Berkeleyan

|

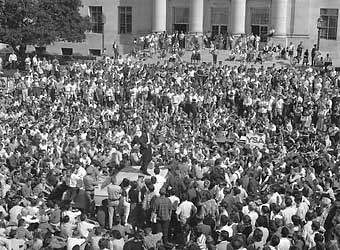

On Oct. 1, 1964, young Mario Savio climbed aboard the police car holding activist Jack Weinberg and energized a growing crowd of students in Sproul Plaza with the first of many impromptu speeches he would give during the months to come. This historic moment will be commemorated in the same location at a noontime rally on Friday, Oct. 8. (Photographer unknown. Photo from Michael Rossman Free Speech Movement Photographs, courtesy The Bancroft Library.) |

Researching the Free Speech Movement

Digitized leaflets, speeches, and oral histories are among the primary sources accessible to any scholar with curiosity and a dial-up account

![]()

| 07 October 2004

Enough time has passed to allow for some historical perspective on the Free Speech Movement — though not so much time that there aren’t numerous participants still alert and able to holler “foul!” at any attempt to encapsulate the movement, let alone draw sweeping lessons from it. But that’s what’s been happening all this week, as FSM veterans and other interested parties convene on campus to note the 40th anniversary of the Sproul Hall sit-in and Sproul Plaza police-car blockade that are generally taken as the movement’s starting point. A variety of rallies, meetings, panels, and other commemorative and educational events are taking place, many of them featuring FSM veterans providing their own memories of those historic days, and offering what lessons they have distilled therefrom. (A schedule of the week’s remaining events is online.)

The memories are by nature personal, even though the movement itself was a model of collective political enterprise. And the lessons? Though they may seem especially clear to the aging participants, they are also there for the crafting by anyone who cares to review the record, particularly since a standard history of the FSM has yet to be written — and perhaps cannot be for another generation. A multitude of FSM-related resources, from the Berkeley campus’s own holdings and elsewhere, are available to anyone with a computer and the requisite curiosity to consult, ponder, and evaluate.

(Those seeking an overview of the FSM might first read The Free Speech Movement: Reflections on Berkeley in the 1960s, by Robert Cohen and the late Berkeley history professor Reginald Zelnik (UC Press, 2002), a synthesis of academic scholarship and personal recollections by participants.)

One-stop scholarly shopping

| Bringing the FSM to life — loud and clear A primary link on the FSM Digital Archive site directs visitors to the campus’s Media Resources Center, whose vast holdings include a significant collection of primary-source audio and visual recordings from the Free Speech Movement, as well as documentary films and radio programs on the subject. Access to the MRC (located on the first floor of Moffitt Library) is more restricted than for other sections of the Library: Berkeley faculty may check out materials for use in class; campus students and staff must use MRC materials on site; during peak-use periods, access is further restricted to those engaged in course-related work. Luckily, it’s possible to hear, emanating from your home computer, dramatic FSM happenings that the MRC has published on the web. As MRC head librarian Gary Handman explains, in the mid-’90s, many people, himself included, starting to think about publishing audio and visual materials, in addition to straight text, via the Internet. It occurred to Handman that Berkeley-based KPFA-FM, “which is always Johnny-on-the-spot for all kinds of movements, fads, and trends,” might have made audio recordings on campus as the Free Speech Movement unfolded in the fall of 1964. His hunch was right. Through KPFA’s parent organization, the Pacifica Foundation, Handman located dozens of hours of produced programs and unedited audio tapes on the FSM. With painstaking editing, he was able to “carve out listenable blocks” from the latter, then use FSM chronologies to figure out their context and order. Now, as a result, the whole world is listening online to hours of oration. Many go directly to Mario Savio’s passionate and oft-quoted speech from Dec. 3, 1964, which includes this famous passage: ”There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!” Web users with RealPlayer software may listen not only to that clip, but to one of the famous removal of Savio from the Greek Theatre stage some days later ... as well as to varied chronologies and overviews of the movement; they may also witness mass arrests of student demonstrators, and sample music from the FSM playlist — Joan Baez warbling folk songs into a Sproul Plaza microphone, a sea of voices singing “Happy Birthday, Mahatma Gandhi,” and a complete concert of FSM Christmas carols (beginning with, sung to a familiar melody, “Oski dolls, pompom girls/UC all the way/Oh what fun it is to have/Your mind reduced to clay”). And much, much more from the heady days of ’64. —Cathy Cockrell |

A few years back, Steve Silberstein, a former head of the campus Library Systems Office who left to create a library-focused software company, donated $3.5 million to fund three FSM-inspired projects at Berkeley, among them the creation of the Bancroft’s Free Speech Movement Digital Archive and Oral History Project. The digital archive collects the campus’s wide-ranging FSM holdings under one virtual roof, providing as close to a one-stop-shopping experience for FSM investigators as any resource affords.

Though not every item has been digitized — and there are no current plans to increase the number of those that have been — the archive serves as a combination FSM bibliography/syllabus simply by listing the hundreds of books, journal articles, commission reports, newspaper stories and editorials, pamphlets, leaflets, press releases, speeches, legal documents, oral histories, and other resources produced both during the height of the movement and in the years that followed.

All of which means that, however you access the FSM archive — either through its front door, or by means of the UC system’s digital portal, aka the Online Archive of California (OAC), which features the FSM Digital Archive as one of eight “virtual collections” — the treasure trove of materials you’ll find is both impressive and a bit daunting.

But first, a brief bibliographic digression is in order: At some point during your browsing, you’ll click on an FSM Digital Archive link and find yourself deep within the OAC’s FSM holdings. While the OAC supposedly serves as a “mirror site” for the Bancroft’s FSM Digital Archive, in fact the mirror effect is inconsistent. For example, the OAC's “Free Speech Movement Archives” are not organized or presented identically to the holdings of the Bancroft’s site.

In addition, on occasion certain holdings maintained by the Bancroft staff do not survive the “migration” to OAC’s servers — though, according to the Bancroft’s Elizabeth Stephens, who created the FSM Digital Archive, they’re not “lost” so much as temporarily “misplaced” during their digital voyage, primarily because of filename changes.

The good news for FSM researchers is that by using the finding aids and search capabilities of both sites, nearly any document desired can be located and — if it’s been digitized — perused on your desktop.

Chronologies — kaleidoscopic and otherwise

Of the six major headings on the FSM Digital Archive’s front page, the one labeled “Chronology” is a good place to start, not least because it links to a single document rather than an overwhelming array of them: a day-by-day account of the FSM that first appeared in the February 1965 issue of the California Monthly, covering the period between Sept. 10, 1964 (one week before Dean of Students Katharine Towle issued a memo prohibiting the placing of information tables at the Bancroft and Telegraph entrance to campus) and Jan. 4, 1965, when the first legal FSM rally was held on the steps of Sproul Hall, following the appointment of an interim chancellor to replace Edward Strong.

Another excellent way to track both the fast-moving events of the time and the range of campus opinions about the nascent movement is to page through dozens of issues of The Daily Californian produced between September 1964 and January 1965; click on the second link). Day-after reporting on each sit-in, rally, or legal proceeding mixes with editorials and letters to the editor expressing the full range of campus opinion. It’s a chronology by other means: kaleidoscopic and absent a central narrative thread, but no less accurate or compelling for that.

Having oriented yourself, you’re free to wander through the archives, pursuing aspects of the chronology that strike you as interesting. Want to read Dean Towle’s own account of her actions? Her oral history is online. So are those of Chancellor Strong, Clark Kerr, Arleigh Williams (dean of men during the FSM, and Towle’s successor as dean of students), and other administrators whose tenures overlapped with the heyday of the FSM — as well as those of people like Robert Truehaft, an “old left” activist attorney who worked closely with the FSM leadership (and spent the night at Santa Rita Rehabilitation Center with many of them following the Sproul Hall arrests of December 1964).

As police drew near during the Dec. 2, 1964, Sproul Hall sit-in, FSM activist Steven Weissman was urged by another occupier to leave by the most expeditious manner — so that, as Weissman later recalled, “We would have a Steering Committee member on campus and not in jail.” (Sid Tate photo for the San Francisco Call-Bulletin, courtesy the Bancroft Library.) |

Other views of the FSM abound — and not just those of key participants ... the Savios, Apthekers, Kerrs, Strongs, et al., whose names have become closely associated with the movement over time. Just two examples:

• A three-part epic poem entitled “Multiversity Lost: A Travesty” appeared in consecutive issues of Spider, a short-lived “countercultural campus literary magazine” (as Reginald Zelnik referred to it) that featured prominently in the so-called “dirty speech” controversy of March 1965. The stanzas sprawl across the screen; alternatively, navigate to the “Pamphlets and Short Works” section of the OAC’s Free Speech Movement Archives, where “Multiversity Lost” is the second of a dozen items catalogued.

• An undated memorandum from Berkeley faculty to “Colleagues and Friends in the Statewide University, Members of Other Colleges and Universities, Fellow Citizens,” in which, following an explanation of the Academic Senate’s overwhelming Dec. 8, 1964, vote endorsing five propositions put forth by the Senate’s Committee on Academic Freedom (widely viewed, then as now, as a major victory for the FSM), nine distinguished members of the Berkeley faculty stated their personal views on the matter.

Collections of primary-source materials are vast and varied in the Free Speech Movement Digital Archive and the Online Archive of California’s Free Speech Movement Archive, not to mention the plainly named Free Speech Movement Archive, developed by Michael Rossman and other FSM activists. The latter contains numerous items of interest not duplicated on either UC site.

Suffice it to say that no one’s curiosity about the events of 40 years ago, no matter how casual or intense, need go unsatisfied in this new era of 1s and 0s — a freedom of inquiry that any FSM activist would surely appreciate.