Berkeleyan

When it comes to algae, SoCal’s loss is our gain

Kelp is on the way. With 200,000 newly orphaned plant specimens to study, Herbarium curators are up to their ears in dried seaweeds, mosses, lichens, and fungi

![]()

| 17 November 2004

Things are abuzz these days at the University Herbarium, where a huge moving van arrived recently to deliver treasures untold. The botanical collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History (LACM) — some 200,000 dried mosses, algae, lichens, and other representatives of the lower plant kingdom (sometimes referred to as cryptogams, for organisms that reproduce by way of spores) — is being transferred to Berkeley en toto.

The collection includes some 50,000 bryophytes (mosses, liverworts, and hornworts) from around the world, especially western North America; 70,000 algae; and 85,000 fungi, with an emphasis on those from Central and South America. The first half of the collection arrived last month in 60 large upright storage cases — bringing much excitement to and portending much work for herbarium curators in charge of preparing the dried plant specimens for scientific study.

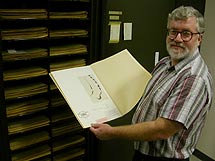

University Herbarium director Brent Mishler shows off a specimen of Porphyra naiadum, a genus of algae related to the edible sea vegetable nori. This specimen was collected by biologist E. Yale Dawson in 1946 off the coast of Baja California. (Barbara Ertter photo) |

“We already have lots of specimens from Northern California,” says Moe — but “nowhere near” as complete a collection of seaweeds from the California coast as the herbaria will now possess.

The L.A. museum was a Southern California herbarium “megacenter” for non-vascular plants, to which a number of academic and scientific institutions contributed specimens. Over the decades it traded away its flowering-plant specimens and accumulated, in exchange, a “fantastic” collection of cryptogams, says Professor Brent Mishler, director of the University and Jepson Herbaria at Berkeley (whose own archive of several thousand specimens, gathered while he was a student at Cal Poly Pomona, became part of the LACM collection).

Being a county-supported institution, the museum has been subject to severe budget cuts in recent years. When Mishler learned of its troubles about eight years ago, “the first thing I did was to try to convince its directors to keep the program there,” he says. When that failed, and LACM made the final decision to divest itself of its cryptogams, he began a lengthy process of negotiation to acquire the orphaned collection. “It was in everybody’s best interest to keep it here in California,” Mishler says. Research botanists Paul Silva and Dan Norris donated the funds needed to move the collection to Berkeley.

The transfer increases the campus’s plant collection by 10 percent, to 2.2 million specimens. Between the University and Jepson Herbaria, Berkeley now has the fifth-largest plant collection in the nation and the fourth-largest collection of bryophytes, plus a strong research program in the botany of cryptogams.

LACM’s collection “goes back at least to the mid-1800s and conceivably even earlier” and includes plant life “from every continent,” says research associate and moss expert James Shevock. “The most remarkable thing is to have access to all of these Southern California things that were in warehouses for years, not available to researchers.” Scientists could potentially learn a great deal, for example, about the original botany of Southern California, including Los Angeles — where much of the land has been paved over and original flora (and fauna) have disappeared. “It would be really great to understand the collecting history of that part of the state,” Shevock enthuses, “and this may help us understand when non-native species first appeared there.”

“It’s a great feeling,” Shevock says of the vast new acquisition. “I’m dying to get into the cabinets and see what is in there.”