Berkeleyan

Cal receiver is wide open to life’s possibilities

His grandfather is a USF legend. His father was a Golden Bear. Now Burl Toler III looks to Saturday’s Big Game — and beyond

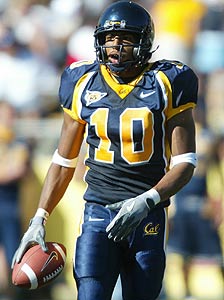

![]()

| 17 November 2004

Cal’s Burl Toler, 21, has found that the lessons of a college-football heritage — such as the importance of determination and perspective — come into play off the field, too. (Michael Pimentel photo) |

For Toler, though, a remarkable pigskin pedigree — his grandfather was a star on a standout college team, his father a Cal linebacker — has yielded a Big Picture outlook. Football is serious business, especially at the heady altitude of No. 2 in the Pac-10 and fourth nationwide. But it’s not the only game in town.

“I see a lot of things a little differently,” says Toler, a 21-year-old Bay Area native whose perspective has its roots in the Jim Crow days of the Deep South. In 1951, his grandfather (and namesake) led the USF Dons to a flawless 9-0 record, only to be denied a trip to a major bowl game — traditionally held south of the Mason-Dixon line — because the team had two African American players, Toler and future NFL great Ollie Matson. To its everlasting credit, the team turned down the chance to play in another postseason game when the invitation came with strings: Toler and Matson would have to stay home.

“It was just a tribute to them,” says the younger Toler of the Dons’ refusal to play ball with segregationists. (His grandfather, he says, talks about the experience “a little bit, but not too much.”) It’s hard for this generation of student athletes to appreciate how many barriers have been shattered — or what it took to shatter them, Toler observes. “I think people nowadays kind of take it for granted,” he says. “For us, it seems far-fetched to have that kind of intense racism. We can’t even relate to that.”

But he does relate to the examples set by his grandfather and then his father, both of whom found success on and off the gridiron.

Soon after graduating and being drafted by the Cleveland Browns, the elder Toler suffered a career-ending knee injury during an all-star game. One dream dashed, Toler simply ran a different pattern. He became a middle-school teacher, the first black secondary-school principal in the San Francisco school district, and, in 1965, the first black referee in NFL history.

His son, Burl Toler Jr., a walk-on who blossomed into a starter at Cal in the mid-1970s, walked away from a shot with the San Diego Chargers for a career as an architect.

And now Burl III, a social welfare major, is weighing his post-college options — either mentoring kids, “traveling the world,” or heading to the NFL scouting combines in advance of next April’s pro-football draft.

“Seeing my grandfather and my dad doing other things steered me away from just doing football my whole life,” he explains. More generally, his strong family ties — he has four siblings, including a younger brother, Cameron, who’s now a Cal Bear freshman — have influenced his ambitions. “I see myself working with kids,” he says.

Toler will have lessons of his own to impart. A star athlete at Bishop O’Dowd High School, he hoped to be recruited by Cal. Although he failed to get a scholarship offer — a major disappointment — he did earn admission to Berkeley and, like his father, joined the Bears as a walk-on. He emulated his father in another way as well: He played in 10 of 11 games in 2001 as a true freshman, and 11 of 12 in 2002. Last season he stepped in for the injured Jonathan Makonnen, the Bears’ top receiver in 2002, to become the team’s second-leading receiver with 48 catches and 609 yards.

“My dad said I should never give up, good things can still happen,” Toler recalls. “Making the team was a testament to what my dad had been telling me.”

Injuries, however, have taken their toll on Toler. He’s suffered from tendinitis in both knees “on and off for three years,” and the condition has grown progressively worse, forcing him to sit out the past four games. For a player who hates missing practice, much less actual games, the bench is the worst seat in the house.

“It’s hard no matter what,” he says of watching from the sidelines. “If we’re blowing a team out or if we’re losing, it’s hard.”

He’s still day-to-day, but Toler has improved enough to start practicing again, and expects to be ready for the Big Game. That will be good news not only for the Bears — who struggled against Oregon earlier this month with three injured receivers — but for Toler’s large extended family, many of whom can be found at Memorial Stadium when the team’s at home. Naturally, that includes his grandfather.

“My whole family’s excited about this season,” Toler says. “I have so many people at every game. I just love playing in front of them.”

With luck, he’ll get the chance this weekend, and just might go to the Rose Bowl, too — a trip Cal hasn’t made since 1959. Whatever his football fortunes, though, the big treasure is the legacy passed down by his father and grandfather.

“They let me know I can do anything I want to do, and they’d be behind me 100 percent,” Toler says. “And I learned never to give up.”