Berkeleyan

J-School's Danner helps lift the curtain on the recent Iraq election

The U.S. view: 'If something doesn't appear on camera, it didn't happen'

![]()

| 16 February 2005

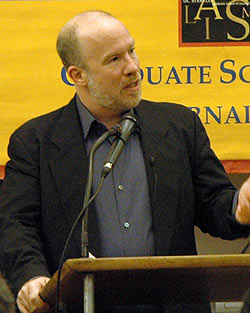

Mark Danner, back from two weeks in Iraq, said journalists and their audiences suffer from "tunnel vision"; in the battle for public perception, most are missing the larger picture. (Bonnie Azab Powell photo) |

The Iraqi driver had tried hard to pick him up. Danner found out later that the man, who carried New York Times identification papers and spoke English, had been forced to get out of his car at a U.S. checkpoint and walk on his knees, hands on his head, for 200 yards over rough cement. A soldier then held a rifle against his temple while his car was searched. Even with journalists, such procedures are routine in the embattled Iraqi city, said Danner.

"The first lesson of this story is that Baghdad was locked down," he emphasized to a standing-room-only crowd at the J-School during a Feb. 10 talk. Danner had just returned from two weeks in Iraq, where he'd been reporting on the election for The New York Review of Books. The author of the 2004 book Torture and Truth: America, Abu Ghraib and the War on Terror has visited Iraq several times in the past few years.

Danner gave a gritty, behind-the-scenes view of how reporting works - or doesn't - in Iraq. The media are "shooting through a straw," he said, unable to see or know what is happening except in a handful of "secure" locations. While the media and the world to which they report have no inkling what lies outside that tunnel vision, the U.S. military, the insurgents, and the Iraqi election commissioners are very much aware. The real battle in Iraq right now, according to Danner, is the battle for public perception.

Any report in a storm

Covering the election or anything else in Iraq was no easy assignment for Danner and other journalists. He described how the dusty beige buildings of Baghdad are almost entirely obscured by a "fierce gray concrete world" made of concrete, barbed wire, and iron tank traps. Streets are basically concrete tubes with 15-foot walls - evocatively called "Berliners" - shielding the buildings. Twisting little mazes lined with additional security devices lead into the hotels and government buildings. There are checkpoints everywhere, requiring passengers to get out and wait in barbed-wire cages while their vehicles are searched.

"The primary thing in journalists' lives - negotiating these amazing obstacles, dealing with this overwhelming paranoia all day long that someone is going to shoot at them - is not in their reports," Danner said.

While talking to a Jordanian security expert, he had wondered aloud how anyone, not just reporters, was able to work under such psychological conditions in Iraq. The man had laughed and said, "You have to realize something: Here, you're not a human being, you're a commodity," Danner quoted. And the American flavor of that commodity can fetch a price between $500,000 and $1 million in ransom money. When Danner expressed disbelief he could be worth that much, the Jordanian replied, "I had to ransom four Egyptians last week and they cost $250,000 each. Egyptians!"

'A war fought with images'

On Election Day, once Danner caught up with New York Times Bureau Chief John Burns, the atmosphere in their part of Baghdad was eerie. There was not a person, or even a dog, to be seen on the streets. Given how tightly the city was locked down, they decided to walk to the nearest polling place, which still required clearing several checkpoints. There, in a school behind a cordon of Iraqi police, they found about 200 Iraqis in long lines, voting.

"It was a remarkable thing. An extraordinary thing," said Danner. "We had no idea that there would be anyone inside."

They went to work gathering material for their stories. Danner read some of his notes aloud for the

J-School audience ("Who are you voting for?" Answer: "I can't tell you - this is a democracy!") and talked about the 38-year-old female engineer he had met (and obviously been smitten with). She had summed up why most Iraqis were risking their lives to vote: "We need security, stability..We just want to live a normal life." Other interviews convinced Danner that Iraqis were seizing "the chance to take positive political action. They did not want to talk about the Americans, the occupation, or Saddam. Nothing. Zero."

Burns and Danner took a break before trekking to the next polling place and watched CNN, where they heard to their amazement that 72 percent of Iraqis were voting, a figure he called "utterly fictitious. All of the numbers you heard on Election Day were utterly fictitious." Covering elections usually means visiting as many polling places as possible, but in Baghdad the military was allowing cameras at only five out of the more than 1,000 locations - unsurprisingly, at the ones with the heaviest security.

There were roughly 250 insurgent attacks on that day, Danner told the audience, representing the highest level of attacks since the occupation began, including nine to eleven suicide bombings. But since none occurred at the heavily guarded polling places where the press had set up, to his knowledge none were on the air or photographed.

The security managed to ensure that the election story would not be one of death and destruction - at least, not at the polling places.

"The insurgency in Iraq is a political war and a war fought with images," Danner said. "The American military is extremely conscious that if something doesn't appear on camera, it didn't happen." That is not because they are trying to hide evidence of the war's going badly, he explained. On the contrary, "these guys believe they're winning the war, that the war is essentially over, but the media isn't reporting it that way, because the press loves bombings." He recounted a meeting he had had with a U.S. military representative who had complained bitterly about the amount of coverage a suicide bomber trying to get into Prime Minister Ayad Allawi's compound had received. The man had succeeded in killing no one but himself - but the headlines were "'Chaos in Baghdad!' Boom!" said the soldier.

And that's what they would have read, or something like it, if any of those Jan. 30 attacks had happened at the polling places where the cameras were, Danner acknowledged.

The Sunnis stayed home

Danner said he had only opinions and educated guesses to share about what the election would ultimately mean for Iraq. Ultimately, the election was a political success, he said, one that inspires cautious optimism in him for Iraq's future stability.

Based on his eyewitness estimates of how many ballots had been torn off from pads, Danner thought that perhaps 40 to 50 percent of eligible voters had participated. The important thing was that a lot of people had risked their lives to do so, and that "the insurgency now no longer offers a political avenue that is more viable in some way than the established avenue put in place by the Americans and the interim government," Danner said. "There is some legitimacy [for the new government]; that is incontestable."

However - and this was a big however - he reminded the audience that the Sunnis had for the most part stayed home. Whether they were scared off by the death threats made by the insurgency or were protesting their perceived exclusion from the slates of candidates, nobody knows. But their non-participation means that the government will not be an accurate representation of Iraq's citizens, and yet the constitution it is charged with drafting will have to include their concerns or risk being vetoed by the three Sunni-majority counties, which would be enough to torpedo it - should the Sunnis come out to vote on that occasion.

About one thing Danner was sure: "It's clear that Americans and Iraqis will continue to be killed in the interim, and that U.S. troops are going to be needed [in Iraq] for a long, long time."