Berkeleyan

Obituary

Leo Brewer

![]()

02 March 2005

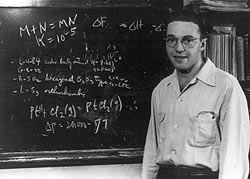

Leo Brewer as a young assistant professor in 1948. |

Widely regarded as the founder of modern high-temperature chemistry, he contributed in fields ranging from organic chemistry and astrochemistry to ceramics and metallurgy.

"It is probably fair to say that Leo Brewer contributed significantly to our understanding of the chemistry of almost every element of the periodic table," said Robert E. Connick, professor emeritus of chemistry. "He created the field of modern high-temperature chemistry."

Born June 13, 1919, in St. Louis, Brewer received his undergraduate degree from the California Institute of Technology in 1940. On the recommendation of Linus Pauling, who went on to win two Nobel Prizes, he entered the chemistry graduate program at Berkeley; only 28 months later, in 1943, he completed his thesis work on the effect of electrolytes upon the rates of aqueous reactions.

He was immediately asked to join the top-secret, wartime Manhattan Project to develop an atomic bomb. He headed a group that was charged with predicting the possible high-temperature properties of the newly discovered plutonium, then available only in trace amounts, and with providing materials for a crucible that would contain molten plutonium without contaminating it. To complete his task, he studied the behavior of all the elements at high temperature, and, unsatisfied with any existing materials for a crucible, experimented with new sulfides of thorium and cerium, which proved successful. Brewer's new crucibles were ready when the plutonium became available.

In 1946, following his service with the Manhattan Project, Brewer was appointed an assistant professor of chemistry at Berkeley. He rose through the ranks to become a full professor in 1955.

The combination of theory with experimentation that he exhibited during his World War II work marked his research throughout his distinguished career. Although his research covered an unusually wide range of subjects and employed many different techniques, from theory to spectroscopy, he focused primarily on high-temperature thermodynamics, materials science, studies of metallic phases, and the development of metallic-bonding theory. He was also involved at different points in his career with astrophysics and ceramics.

Though fundamental in nature, his research had practical applications as well, from nuclear reactors to space sciences, including the development of a corrosion-resistant stainless steel based on chemical reactions he described. He was much sought-after as a consultant.

In addition to his academic appointment, Brewer was an investigator at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, where he headed the Inorganic Materials Research Division from its inception in 1961 until 1975. He was also active in many professional societies and on the editorial boards of several journals.

His work - published in nearly 200 articles and in his 1961 revision of a well-known 1923 thermodynamics textbook - was recognized with many awards, including election to the National Academy of Sciences. He also received the E. O. Lawrence Award of the Atomic Energy Commission, the Palladium Medal of the Electrochemical Society, the Leo Hendrik Baekeland and Coover Awards of the American Chemical Society, the Hume Rothery Award of the American Metallurgical Society, and fellowship in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Society for Metals. Upon his official retirement in 1989, he was presented with the Berkeley Citation and a symposium was held in his honor.

Brewer was a caring and gifted teacher who taught freshman chemistry as well as more advanced courses. He received the Linford Award for Distinguished Teaching from the Electrochemistry Society in 1988. He also directed 40 doctoral students and nearly two dozen postdoctoral fellows over the course of his career. Beyond the physical sciences, Brewer was passionately interested in native California plants and even had a species of manzanita named after him.

He is survived by his three children: Roger Brewer of Portland, Ore.; Gail Brewer of La Caņada; and Beth Gaydos of Cupertino; and six grandchildren. His wife, Rose Strugo Brewer, died in 1989.

Funeral services were held Feb. 25 at Oakmont Memorial Park in Lafayette. The family requests that memorial contributions be made to the Department of Chemistry (420 Latimer Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720-1460) or to the California Native Plant Society (2707 K Street, Suite 1, Sacramento, CA 95816-5113).

-Jane Scheiber, College of Chemistry