Berkeleyan

Beyond the lobectomy?

Berkeley researchers create model of brain's electrical storm during an epileptic seizure

![]()

| 02 March 2005

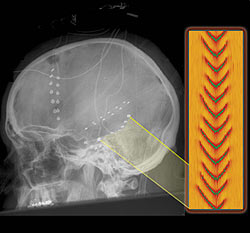

A lateral skull radiograph of an epilepsy patient with a series of electrodes implanted into his brain. The electrodes allowed neurologists to map the electrical activity produced during the patient's seizures in preparation for brain surgery. (Image courtesy UC Regents) |

"We're trying to get to the underlying state of the brain that leads to these seizures," said Mark Kramer, a Ph.D. student in applied science and technology. "Our hope is that the model can highlight potential areas where a seizure can be stopped."

There are several possible causes for the abnormal signaling in epilepsy, including illness, injury, abnormal brain development, and an imbalance of the chemical neurotransmitters that convey messages in the brain. Some seizures begin in a very specific area of the brain called the "seizure focus" before spreading out; others, particularly ones linked to genetic causes, appear to start simultaneously in various parts of the brain.

What is clear is that during a seizure, a strong pattern of electrical signals suddenly emerges from the random fluctuations that characterize normal brain activity. The strong waves moving across the cortex may cause sudden, unpredictable sensations or uncontrollable movements.

"Normal brain waves would resemble jagged lines with no apparent pattern or order on an electroencephalogram," said Andrew Szeri, professor of mechanical engineering and applied science and technology, and principal investigator of the study. "But in the brains of epilepsy patients, the spreading of a seizure is made manifest by strong coherent waves of electrical activity in the cortex."

To model this behavior, the researchers adapted stochastic partial differential equations to describe the architecture of the brain - the same class of equations used to spot trends in the stock market, the weather, or other complex systems that can be affected by random events. They simulated the hyperexcitation of neurons in a portion of the brain and found that the stimulus produced traveling waves of electrical activity.

To test the accuracy of their model, the Berkeley researchers teamed up with physician Heidi Kirsch, assistant professor of neurology at UC San Francisco's Epilepsy Center. Kirsch was treating a 49-year-old epilepsy patient whose seizures were not reliably controlled by medication. The patient was diagnosed with mesial temporal sclerosis, a condition in which the hippocampus, the part of the brain that organizes memories, is smaller than normal.

"We estimate that two-thirds of patients with epilepsy will respond to medication," said Kirsch, who also co-authored the paper that resulted from this research. "For a number of the remaining one-third of patients, surgical removal of the part of the brain where seizures begin may offer a cure. The goal in seizure surgery is to find one spot where the seizure comes from and, when taking it out, to not hurt the patient."

Before surgery, neurologists needed to map the region where the patient's seizures originated to ensure that they removed only what they needed to. To help neurologists observe the patient's seizures, 64 electrodes were implanted into his brain for a week. The researchers were thus able to obtain data from six of the patient's seizures, for comparison with the mathematical model they had created.

"The wave signals from both the model and the observational data were similar in shape, frequency, and speed of propagation," said Kramer. "That suggests that our model is pretty accurate."

The researchers say this is an early step in creating a model that can provide far more detail about the inner workings of the brain than is possible with electrodes alone.

"Electrodes reveal the consequence of the abnormal brain activity, but they don't get at the cause," said Szeri. "If we understand why and how these strong coherent waves progress over the surface of the brain, then we have a hope of doing something to change the situation by disrupting the signal."

Much as a computer model can reveal more about the structural integrity of a building or the causes of a developing hurricane than is practical or desirable through direct observation, a computer simulation of a brain during a seizure could potentially provide a fuller picture of how and why electrical signals misfire.

"This model could provide insight into the pathophysiology of the spread of a seizure," said Kirsch. "Further down the line, this could also help us model the impact of medications and other interventions, to theoretically test how drugs with certain mechanisms will impact the brain."

The researchers point to ongoing research to develop interventions to halt epileptic seizures. Examples of potential directed therapies include focal cooling, in which the part of the brain experiencing a seizure is literally chilled to dampen the seizure, and electrical stimulation of the affected area of the brain to counter the seizure as it's forming.

"Our hope is to provide a model that can be used to evaluate potential seizure treatments so we can move beyond the need for lobectomies," said Szeri.

The researchers' paper will appear in the March 22 print issue of the Journal of the Royal Society of London Interface.