Berkeleyan

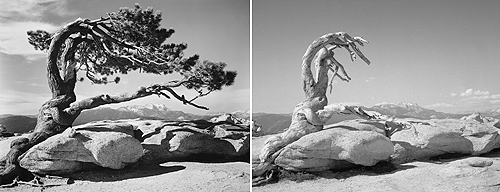

Two views of Sentinel Dome. Ansel Adams made the left photograph in 1940; by 2002, as seen in the photo at right - taken from the spot where Adams had stood - the once-vibrant Jeffrey pine had been killed by drought. (Credit) |

Unlocking Yosemite's mysteries

In a new book and Berkeley Art Museum exhibition, Rebecca Solnit teases history out of the rocks

![]()

| 05 October 2005

Ansel Adams' black-and-white photographs of Yosemite Valley, as stark and alien as moonscapes, brilliantly capture an austere, unpopulated world of rock and trees and waterfalls, even today offering eloquent testimony to the timeless majesty of nature.

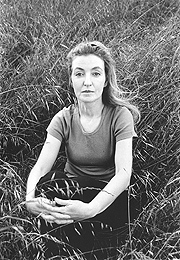

Rebecca Solnit |

"The metaphor we so enjoyed deconstructing is 'time is a river,'" Solnit says. "The river functions as a metaphor for time, but of a time that doesn't move in that smooth, consistent flow that Western, technological, rational descriptions would like it to."

"We" is Solnit and her two collaborators, photographers Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, whose shots of Yosemite landmarks such as El Capitan and Bridalveil Falls add vital new information to classic archival photos. On four trips in as many years, the trio journeyed to the exact locations where Adams, Eadward Muybridge, Edward Weston, and others created our most enduring representations of the valley. By replicating these iconic images - and ingeniously juxtaposing their own pictures with shots dating in some cases to the 1850s - the trio hoped to demonstrate what Solnit calls "the constructedness of versions of place."

"You can see Ansel Adams going and standing at Lake Tenaya and constructing his version of the sublime, while Muybridge in the same place is constructing a completely different version, and Edward Weston, who stood two feet away from Adams, is doing a slightly different version, and you can really see how infinitely interpretable a place is," she explains by phone from her home in San Francisco. Documenting physical changes in the landscape since 1872, for example - when Muybridge was exploring Yosemite, and arguments raged about Darwin, God, and man's place in the world - also resurrects its history and puts humans back in the picture.

"Yosemite was not a virgin wilderness, as a kind of environmental iconography has it," Solnit says. "It was somebody else's homeland. And once you acknowledge that, you can stop having that Madonna-and-whore relationship to landscape and nature and the environment . and go on to look at these other ways of touching the place and being in the place and realize that there really isn't a separation."

A Berkeley journalism grad (and sometime instructor) whom the New York Times recently dubbed a "free-range intellectual," Solnit has roamed this territory before, in such acclaimed books as Wanderlust, Savage Dreams, and River of Shadows: Eadward Muybridge and the Technological Wild West. Her fascination with the trailblazing British expatriate Muybridge - who won fame in the 1870s by using high-speed photography to reveal animals' imperceptible movements, and notoriety by killing his wife's lover with a gunshot to the chest - led her deeper into both photography and Yosemite, and eventually into a fruitful creative partnership with Klett and Wolfe.

"Mark had a long interest in Muybridge that preceded mine," she says, noting that in 1991 Klett had applied a technique called rephotography - replicating archival photos as closely as possible by shooting from the same spot, at the same time of year, and under similar conditions - to a panorama Muybridge had made of 19th-century San Francisco. "Even though we always think of scholarship as something that comes out of and results in language and that is done in dusty, bookish places, Mark has used photography as a research tool, and an extraordinarily sophisticated one. By rephotographing Muybridge's panorama he came to understand how you could manipulate time, and do some really interesting things with that."

Dismantle or deconstruct?

As for Adams, Solnit admits she's softened her attitude toward "the great Oedipal father of American landscape photography," whose vision of nature she and Klett roundly rejected in the 1980s. "Adams' work seemed so strong and so definitive, he was so technically polished, that a lot of people were, like, what do you do after that?" she says. "At the same time, people rebelled against it, because they wanted a different kind of landscape, seen with a different kind of vision, with different kinds of technologies and different kinds of human-natural relationships.. Adams had constructed something that was very perfect in its own way, and the job of Mark's generation was to dismantle if not deconstruct it, and to start over with what else could be said about landscape."

The juxtaposition of images in Yosemite in Time, in contrast to individual photos themselves, shows a continuing process of life, death, and change. Trees shrivel or disappear, thickets of brush take over clearings, the Merced River - in one stunning panorama - shifts its course. Not unlike Muybridge's early experiments at using film to illustrate motion, the effect is to inject a sense of narrative continuity into the formal, monument-like landscapes proffered by Adams and so many of his colleagues.

That narrative, Solnit emphasizes, must include Native Americans, "who, with John Muir and Ansel Adams and the environmental tradition, were erased from existence, while the Park Service rendered them invisible by burning down their villages, evicting them repeatedly, and trying to establish this as a place where, in the words of the Wilderness Act of 1964, man is only a visitor, and human beings don't belong."

Making pictures "in which nature and culture are not at war with each other," she adds, "has been one of Mark's goals all along."

Solnit describes the collaboration as "a very improvisational project." She first came across the coordinates for Muybridge's Yosemite locations while researching River of Shadows, but soon discovered that Adams, Weston, and Carleton Watkins had taken photos from nearly identical spots. Before long she, Klett, and Wolfe were trekking to Yosemite, engaged in a three-way dialogue to explore the question, as Solnit puts it, "How do we arrive at a more humane, less conquistador, less discovery-oriented sense of an inhabited wilderness - a place that has always been somebody's home, and that is home to so many of us in some larger way?"

They were interested, too, in a more fundamental question: How long does it take to truly see something, as opposed to merely looking at it? Berkeley's own Joseph LeConte, Solnit notes, once wrote about visiting Yosemite in 1870 "and needing, in that wonderful Victorian sense of expansive, luxurious time, half a day to see the view from Glacier Point."

An activist as well as an author, Solnit believes in slowing down, and sees no conflict between Victorian-style idleness and the kinds of political action she advocates regularly on the website TomDispatch.com or in her book Hope in the Dark.

"I think that moving fast, producing and consuming a lot, is what fires the engine of consumer culture - in some ways the world seems like an enormous factory of production and consumption," she explains. "One of the great methods of resistance for factory workers is the slowdown. And so I feel that every act of slowness - walking instead of driving, making things from scratch instead of buying them in packages, and that kind of stuff - it's not lying down in front of the bulldozers, which I've also done and also support, but it can be an act of resistance.

"All art, not just this project, aims to encourage people to move more slowly and be more thoughtful."

On Sunday, Oct. 9, at 2 p.m. in the Berkeley Art Museum Theater, Rebecca Solnit will join her collaborators, photographers Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, and Berkeley faculty members Carolyn Merchant and Margaretta Lovell in a panel discussion based on the Yosemite in Time exhibit, on view at the museum through Dec. 23.

Photo credits

Left:

Jeffrey Pine, Sentinel Dome, Yosemite National Park, California, c. 1940; digital reproduction of an original photograph by Ansel Adams; 20 x 24 in.; courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona © Trustees of the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

Right: Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe: The trunk of the Jeffrey pine, killed by drought, Sentinel Dome, 2002; digital inkjet print; 20 x 24 in.; courtesy of the artists.