Berkeleyan

Campus librarians collect top honors

Two 'gatekeepers to information' are cited for distinguished contributions to music, transportation research

![]()

| 12 October 2005

Later this month the Berkeley division of the Librarians Association of the University of California will honor two of its own, the recipients of the 2005 Distinguished Librarian Award: John Roberts of the Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library and Daniel Krummes of the Harmer E. Davis Transportation Library. Each represents what the association calls "the highest ideals of librarianship on the Berkeley campus." The Berkeleyan recently spoke with each.

John Roberts

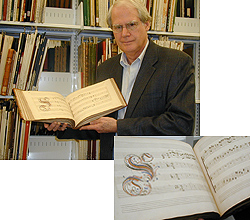

In the course of building the campus's music collections, a "small but interesting" part of John Roberts' job is helping acquire rare materials. Here he displays a manuscript collection of Italian arias and cantatas from the exile Jacobite court (c. 1700). Temperature and humidity controls in the new Hargrove Music Library provide optimal protection for such items. (Cathy Cockrell photos) |

Roberts has headed Berkeley's music library since 1987, when the collection had long been bursting at its seams. Thus, space became a major theme of Roberts' career at Berkeley (as it has been for eight music-department chairs over three decades), right up until July 2004, when the elegant and up-to-date Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library opened its doors. The three-story building has more than twice as much room as the collection's prior home in nearby Morrison Hall, and a climate-controlled section for rare materials. These two improvements, for Roberts, were the most important requirements for the collection's new home. To the extent that he helped make the Hargrove a reality, it is his most important contribution to the campus, he believes.

Roberts spoke from his bright, sparely appointed office on the building's southwest corner, proudly noting that the library has long been considered one of the best (some say the best) university music collections in the country. Designed to support the research and teaching interests of the department (especially music history, ethnomusicology, and composition), it holds 190,000 volumes, 60,000 sound recordings, and thousands of microfilms and microfiches. Roberts works closely with faculty to round out the collection with new materials from around the world, and he has also overseen innovations in access and delivery, such as a streamed-audio network, allowing students to do assigned listening via a web interface.

The Hargrove also houses a number of rare books and scores, manuscripts, and other archival materials useful to faculty and grad students in their research. "You can see things in an original," Roberts observes, "that you can't see in a reproduction": different colors of ink, the watermark, the paper itself. (The Hargrove owns, for example, an 11th-century chant manuscript; its original notes are penned in brown ink, while an alternative melody, in red ink, was overlain on the parchment at a later time. On microfilm, all the notes would appear the same - and the story the manuscript has to tell would be lost.)

A music scholar in his own right (he received his Ph.D. at Berkeley in 1977 and has a part-time faculty appointment), Roberts once discovered on the library's shelves the only complete score of the long-lost Alessandro Scarlatti opera L'Aldimiro (which the department then brought to the stage at the 1996 Berkeley Festival, the first performance of the work in three centuries). He was later instrumental in acquiring a unique copy of another Scarlatti opera, Gl'inganni felici, in a fierce bidding war at a Paris auction house. "It's a small but interesting part of my job," he says.

The Mitchell Fund, a major endowment secured during Roberts' tenure, has put the Hargrove in a strong position to compete with other universities for manuscripts of this caliber - though it is sometimes outbid by private collectors with unlimited resources. He does not seek out autograph manuscripts by major composers, as a rule. "I don't think you get value for your money," he says. "You're paying for the prestige of owning it. But that's not why we're buying things. We're buying them so students or faculty can study them."

Roberts' long years of leadership in the world of music librarianship, cited in his nomination for the LAUC award, include a three-year stint as president of the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives, and Documentation Centres. He continues to follow actively major issues he dealt with in that role (among them the globalization of copyright law), while focusing his campus efforts on building Berkeley's music collection to meet evolving demands.

"The whole field of music scholarship and study has broadened in recent years," Roberts says. "There's not only more interest in music from different cultures, but in popular music, jazz, and other vernacular musics. Today all sorts of music are being subjected to academic study."

Daniel Krummes

Transportation librarian Dan Krummes, who studied anthropology as a graduate student, is fascinated with the "human aspects" of ocean travel in the steamship age. He haunts antique shops to collect logo-marked chinaware and "funnel ashtrays," several of which are pictured here. The Harmer Davis Transportation Library collects materials on virtually every known form of transportation, from lost technologies to futuristic schemes. (Deborah Stalford photo) |

On Krummes' turf, the theme tilts toward the sea (and steam-ships in particular), with stylized ceramic teapots depicting the "Teatanic" and other ships, antique funnel ashtrays (shaped like steam stacks and used as marketing give-aways), a '50s-era poster from French Lines shipping company, 19th-century lithographs of disasters at sea and rough North Atlantic crossings.

Krummes' tenure at Berkeley, like Roberts', can be measured in decades. He arrived as an undergrad in 1968 and was hired as a library assistant in 1976, after serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in West Africa and completing a master's degree in anthropology at Ohio State. At that time, the library had been relocated from the Richmond Field Station - where for more than a decade it sat literally in the middle of the multi-campus Institute for Transportation Studies (ITS), amidst faculty, students, and researchers - to the fourth floor of McLaughlin, with most of the faculty offices three stories below.

One of the oldest and largest transportation libraries in the country, Harmer Davis focuses on urban transportation, aviation, traffic engineering, and intelligent transportation systems. Krummes' goal as its guardian - and his achievement, according to ITS director Martin Wachs - has been to reintegrate the library into the life of the institute, fostering close connections between library staff and the faculty and students.

"Librarians can see themselves as gatekeepers to information," Krummes says. "We've tried to make certain that the gate is always open; we've lured the people in." Students come to libraries with questions, yet are often hesitant "to ask the question that's really on their mind," he's observed. "We work really hard, particularly the public-service staff, to make sure the question gets asked and answered - and that the right question is asked."

According to Wachs, Krummes works masterfully with library employees, "empowering, respecting, giving them confidence that they can become experts in transportation" - a field of librarianship whose excitement, and challenge, lies in its multidisciplinary nature. "It's a happy place. There's a high level of service, and people stay a long time."

Although Krummes has been known to utter the word "teamwork," he is careful to put distance between that overworked term and what the transportation library staff has together accomplished.

"There's a lot of talk out there about being team players," he says. "But what makes this library work is that people really are a team.. The 'glory work' might be when the reference librarian says 'Bingo! This is what you're looking for!' But she was able to find it because one of our student employees input a record correctly. And the cataloger thought of the end user, as opposed to 'what is the rule?' And the student shelved the book so that it's really there.'"

Krummes' own research interests are idiosyncratic and esoteric. His passion for boats dates back to his childhood in Vallejo, where his father, grandfathers, and a great- grandfather all worked in the Mare Island Naval Shipyard, and where, throughout his youth, nuclear-sub launches became festive community events. Since that time, Krummes has developed a special fascination with the steamship age, which stretched roughly from 1850 to 1970.

"People interested in steamships often come at it from more of an engineering bent" - gross tonnage, length, twin-reciprocal engine capacity. Krummes is taken, instead, by the human aspect. Logo-marked steamship chinaware, for instance, offers "a fascinating comment on how steamship owners viewed their companies; they were very proud of their enterprises."

His 1997 reference book, Dining on Inland Seas: Nautical China from the Great Lakes Region of North America, is now the standard text on that subject - "for all three of us in the world who are interested," he jokes.

A fiction lover and a reader of lightning speed, Krummes is also hard at work on a massive annotated bibliography of steamship tales; a subset on World War II-related fiction, titled "Cruel Seas," can be found online at www.lib.berkeley. edu/~dkrummes/cruel. Having collected and read some 600 maritime novels, he's currently combing through short stories published in mass-market magazines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

"Right now," he says, "I'm working my way through a set of Pearson's Monthly, looking for steamship stuff. I'm up to 1906."