Berkeleyan

|

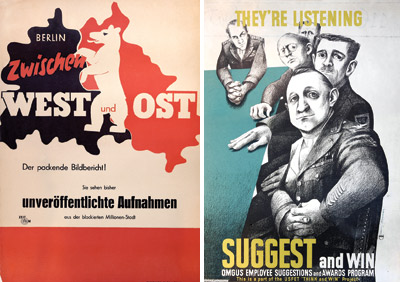

Posters produced by the Office of Military Government / U.S., the occupational authority in Germany after World War II. The office's documentary-film unit was the predecessor of the Marshall Plan motion-picture unit. (Images courtesy Schulberg Productions) |

A man, a plan, a film series

For post-Nazi Europe, recovering from the ravages of war, the Marshall Plan meant billions in U.S. aid - and an unprecedented propaganda campaign aimed at "Selling Democracy"

![]()

| 26 October 2005

George W. Bush, who scorned nation-building as a presidential candidate but embraced it big-time once in the White House, has invited comparisons of U.S. foreign policy - in Afghanistan, in Iraq, in Africa - with the Marshall Plan, America's massive program of economic aid to Europe following World War II.

"SELLING DEMOCRACY" AT PFA |

The European Recovery Program - universally known as the Marshall Plan, after Gen. George C. Marshall, secretary of state under President Harry S Truman - provided billions of dollars in money and materials to war-ravaged European nations from 1948 until soon after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, when aid to Europe morphed into military support. Credited with speeding up the continent's economic recovery as well as restoring democracy to post-Nazi Germany, it extended the offer of aid even to the Soviet Union and East-bloc nations, which declined the help.

"The Marshall Plan was a relatively unique episode in American history," says Berdahl, who notes that the program had both altruistic and geopolitical motives. There was, he explains, widespread concern over "a shortage of food and basic materials to reconstruct normal life after the second World War throughout most all of western Europe, and eastern Europe for that matter." But Great Britain's announcement in the spring of 1947 that it was pulling out of Greece and Turkey added to "American concern about the left-leaning, pro-communist, pro-Soviet political moves that were developing in western Europe," a major theme of Truman's presidency.

A scene from Aquila, an early neorealist film that depicts the plight of an unemployed Italian laborer who's arrested for stealing. Fortunately for him, the authorities realize he's only trying to feed his family, and he ends up working at the Aquila refinery, which is being rebuilt with Marshall Plan aid. The 21-minute film, made around 1950, features a symphonic score performed by the Orchestra of Radio Trieste. It screens at PFA on Nov. 17. (Courtesy Pacific Film Archive) |

Kennan's argument, says Berdahl, "was that Soviet expansionism was age-old Russian expansionism that didn't have anything to do with communism, and that to get involved in an ideological conflict would only intensify the Cold War fever and mislead us from the effort we really needed to engage in to contain Soviet expansion."

If such arguments sound familiar, the resemblance is anything but coincidental. "Against the backdrop of current U.S. efforts to democratize Iraq and Afghanistan, the films of the Marshall Plan have particular resonance," writes curator Sandra Schulberg - whose father was the head of the Marshall Plan motion-picture section - in notes for the series. Lauding the plan's "almost universal reputation for its healing effect," she warns against "cloaking occupational forces in Marshall Plan camouflage."

Berdahl shares that perspective. "I think they're pretty specious," he says of efforts to link America's Middle East policy and the Marshall Plan. "I don't see much validity at all." For one thing, though Americans were promised that U.S. troops would be welcomed as liberators by Iraqis, the reality was vastly different from postwar Europe, where, except in Germany itself, the United States was indeed seen as having freed the continent from Hitler's yoke.

"Secondly, the idea that we could easily create a democratic system in Iraq ignored the tribal nature of conflicts and the containment of conflict historically," Berdahl goes on. "Germany clearly had much more of a foundation and experience upon which to build democratic systems. After all, they'd had constitutional governments for a hundred years, they'd had parliamentary systems of one form or another for three-quarters of a century - they'd had the kind of civil society that made it possible for democracy to take root.. So the idea that it would be easy to set up a democratic state that would be an example throughout the rest of the Middle East was, I think, palpably false, and stupid."

In Hansl and the 200,000 Chicks (1952; screening Nov. 10), the eponymous Austrian hero receives a consignment of Marshall Plan eggs and is soon outdoing his parents in egg production. By the end of the 15-minute film, Hansl is able not just to help support his family but to buy a bicycle for himself. (Courtesy Pacific Film Archive) |

Schulberg writes that, parentage notwithstanding, her interest in the Marshall Plan films developed only recently, "impelled in part by world events that unfolded following Sept. 11." Described by one Marshall Plan scholar as "the largest peacetime propaganda effort directed by one country to a group of others ever seen," the films have rarely been viewed since they were made, and - until a ban on showing U.S.-made propaganda to American audiences was lifted in 1990 - were off-limits to viewers here.

In addition to Berdahl and Nacht, the Nov. 18 panel discussion will include Richard Buxbaum, a professor of international law; Christina von Hodenberg, a visiting professor of history; and Schulberg. For more information, visit the PFA website at www.bampfa.berkeley.edu.