Berkeleyan

The 'soul-satisfying' work of repatriation

Native American staffers at Hearst Museum work with tribal groups to lend - or return - remains, artifacts, and ceremonial objects

![]()

| 03 November 2005

In Indian Country the expert who comes calling, briefcase in tow, is a common butt of jokes, given the troubles these outsiders have been known to bring and the things of value - from prehistoric artifacts to the bones of many ancestors - they have often taken away with them. Last week Otis Parrish and Natasha Johnson of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology visited a Native community in a different spirit, traveling to the Shasta County town of Burney to personally deliver skeletal remains excavated from Pit River territory close to a century ago.

| Native Staff at the Hearst Museum's NAGPRA unit Larri Fredericks, Anthony Garcia, and Otis Parrish |

Rewriting the ground rules

The two Hearst Museum staffers work for a five-member section of the museum charged with fulfilling the letter and spirit of a 1990 federal law, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). They note that most Indian cultures believe the spirit of the deceased is violated if the body is taken from the ground. Thus the disruption and removal of Native remains - for study or display, even for the pleasure of collectors, and at times in the past sanctioned by federal policy - is a deeply felt injury across Indian Country.

NAGPRA changed the ground rules on this matter. It required museums to inventory the Native American remains and funerary objects in their collections, and to share descriptions of the sacred objects, objects of cultural patrimony, and funerary objects in their possession with federally recognized tribes. These tribes, in turn, gained the right, under defined conditions, to visit the collections and claim remains of their ancestors, as well as funerary, sacred, and other objects indispensable to tribes' cultural patrimony.

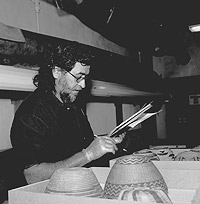

Bruce Stiedle, a Maidu from Moortown Rancheria in Oroville, visited the Hearst Museum in 2001 to examine Maidu tribal items in the museum's collection. (Courtesy Phoebe A. Hearst Museum) |

Ninety-nine percent of those, he says, come from archaeological excavations, including some conducted before lands were inundated by dams and reservoirs or destroyed by construction projects. As a result, most of the skeletal remains in the Hearst Museum can be traced to tribal groups but not to lineal descendants.

'Opening up' the museums

Curators and scholars, at Berkeley and elsewhere, were predictably uneasy about the potential detriment to collections posed by NAGPRA repatriations - which began at the Hearst soon after completion of the major inventories required by the new (and unfunded) federal mandate, in June 2000. Members of the NAGPRA unit, however, have observed an opposite effect. Collections Manager Natasha Johnson, formerly of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., says that museums have gained a new appreciation for their collections, initially because of the required inventory process, and more profoundly as a result of contact with tribes as they send members - often for the first time ever - to view items related to their cultures and in some cases to initiate repatriation claims.

"Every time the tribes come out and interact with the collection, they tell us something new about it, and something more meaningful about it than what we have in our records," she says.

| Celebrating Native American Heritage Month November is Native American Heritage Month, and the campus plans to celebrate with a day of activities on Sunday, Nov. 6, appropriate for visitors of all ages. Noon: Guides at the UC Botanical Garden will lead a tour of plants used by California Native people. 1 p.m.: Hearst Museum cultural attaché Otis Parrish (Kashaya Pomo) will lead a tour of the museum's Native California Cultures Gallery. Through hands-on activities, visitors can also explore ways that Native Americans fashioned necessities from California plants. Noon-1:30 p.m.: Indian- taco sale at the Hearst Museum. Proceeds support the Native American Studies department. 2 p.m.: Performance by the Medicine Warriors Dance Troupe and All-Nations Singers at the Hearst Museum. On Thursday, Nov. 17, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., the Hearst Museum Gift Store will hold a Native American jewelry sale. The store may be found near the museum's entrance. The Hearst Museum of Anthropology is located in Kroeber Hall (Bancroft Way at College Avenue). For information, call 643-7649 or visit hearstmuseum.berkeley.edu. |

According to Hitchcock, "Museums were not very open prior to NAGPRA. It's forced the museums to open up. Tribes come here with some trepidation, because they've heard all of the bad stories about the old days. And when they get here for a NAGPRA visit, they find out they can also schedule a research visit that has nothing to do with NAGPRA." He notes that while museums "are notorious for being sticklers on loaning objects," the Hearst has worked out several short-term loans of ceremonial objects to Klamath River tribes.

To date there have been 18 repatriations from the Hearst Museum under NAGPRA - among them a mummy claimed by the Chugach Alaska Native Corporation (who returned it to the cave where it was discovered in the Prince William Sound area); human remains returned to the Santa Rosa Rancheria, near Fresno, for ceremonial reburial; and an early-19th-century tunic from Alaska's Tlingit tribe. Parrish explains the relatively small number of repatriations to date as "natural," given that many of the small tribes lack the funds for a museum visit and the expertise to do the necessary legal footwork. However, as tribes apply for NAGPRA grants from the National Park Service and for funding from other sources, "the visits to the Hearst Museum are increasing," he says.

Senior Museum Scientist Larri Fredericks is now reviewing archival records on items from tribal groups lacking federal recognition, many of which may be eligible to reclaim items under a state corollary of NAGPRA, the California Native American Graves Protection and Repatria-tion Act of 2001. She also assists tribal members in reviewing museum documents and using museum records to gather information on tribal objects. "A lot of times when tribes come in, the documents are a very scary thing," she notes. "We try to break it down: 'Come on, this is like a mystery we're solving.' They seem to enjoy working with us and we enjoy working with them. Plus we do solve some mysteries."

The fact that there are three Native Americans from different tribes on staff (Fredericks is an Athabascan from Alaska, Parrish is a Kashaya Pomo from California, and Senior Museum Scientist Anthony Garcia is an Apache from Arizona) adds to the visitors' comfort level and is helping the Hearst build positive relationships with Native communities.

"As a NAGPRA program with predominantly Native people, we can be a model," Parrish believes. He feels it's immensely gratifying to be part of returning these human remains back to their homelands" and "to see people do the ceremonies, feel good when they come here. A spiritual essence is created when we do that. And there's a lot of healing to go on yet."