Berkeleyan

Research patently in the public interest

Socially responsible licensing makes Berkeley a leader in the delivery of promising new therapies to the developing world

![]()

| 02 December 2005

As one might expect from the head of Berkeley's intellectual-property operations, Carol Mimura is fluent in the argot of business, sprinkling her speech with frequent references to royalties, profit drivers, opportunity costs, and the ubiquitous bottom line.

But as keen as she is on revenue streams, Mimura, whose office sits at "the junction of science, law, and business," is never more bullish than when she talks about social responsibility. With support from Beth Burnside, the campus's vice chancellor for research, she's helped put Berkeley at the forefront of nationwide efforts to bring new medicines and technologies to those who may need them the most but lack the means to pay for them.

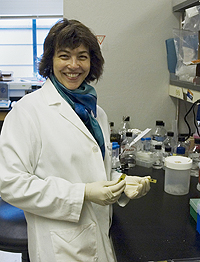

Carol Mimura, acting assistant vice chancellor for the campus's restructured office of intellectual-property management - known as IPIRA - believes it's a "moral imperative" for well-off nations to aid countries with fewer resources. (Deborah Stalford photos) |

Under Mimura's direction, Berkeley's three-year-old socially responsible licensing initiative has thus far yielded more than 10 separate agreements aimed at enabling campus researchers to get the fruits of their groundbreaking labors into the arms of the developing world. Two such deals that garnered widespread attention involved chemical-engineering professor Jay Keasling, a faculty affiliate with the California Institute for Quantitative Biomedical Research (QB3) and the head of the Synthetic Biology Department at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

In one pact forged in 2004, the campus and the government of Samoa agreed to divide equally any commercial proceeds from a promising anti-AIDS drug based on Samoan plant medicine. The drug, prostratin, has long been extracted from the bark of the native mamala tree by traditional healers, who shared their knowledge with the American ethnobotanist Paul Alan Cox. Researchers in Keasling's lab plan to isolate and clone the relevant genes from the tree in order to create a synthetic version in so-called microbial factories. The university would then seek to license the patent to a pharmaceutical company for manufacture and distribution to developing countries.

From idea to initiative: a license to cure "A driving force in my life has been to take scientific good and make it available to developing countries - to use science to make the world a better place," says Eva Harris, an associate professor of infectious diseases in the School of Public Health. "What I've been trying to do throughout my career is to find specific ways to make that vision come true."

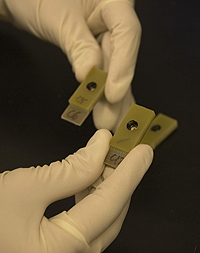

That idealistic impulse led her to Nicaragua, where, while still in her 20s, she helped launch a program to offer poorer countries "a knowledge-based approach" to medical science. "The whole point was to deconstruct what looked like fancy technologies and then reconstruct them on-site with existing materials and conditions," she says. With a group of public-health colleagues, Harris was instrumental in organizing a series of workshops aimed at bringing such technologies - "all this nice science I had learned at Harvard and Paris and all the great places I had worked" - to Central America. Those efforts brought Harris international recognition and, in 1997, a MacArthur "genius" award. With the cash from the MacArthur, Harris founded the nonprofit Sustainable Sciences Institute (SSI) the following year to carry on the mission. It was at Berkeley, where she was soon recruited from UCSF, that an extracurricular collaboration with some electrical-engineering students - "more of a hobby," she calls it - gave rise to a cheap, hand-held device for diagnosing dengue fever, a mosquito-borne disease that strikes tens of millions every year. Modeled on a standard but more elaborate assay, the device employs a computer chip to determine on the spot if a subject has been exposed to a given pathogen - from the dengue virus to HIV - effectively doing the job of expensive (and often inaccessible) hospital equipment. Proving the invention works, however, is a far cry from getting a robust model into the field. And bridging what Harris terms the "no man's land" between basic research and development can be tricky. "Universities do the 'R.' The 'D' is supposedly companies," she observes. And though the nonprofit SSI seemed the perfect medium for bringing the invention along, there was one problem: As with all research conducted on campus, the intellectual property belonged to the university. "Even though we're interested in making this for developing countries," Harris says, "it's actually owned by the university. So early on, when we started patenting it, the concept was, Can we work out a deal where, if they want to license it to a for-profit company for whatever use in the First World - which could be very interesting, because you could diagnose any infectious disease, you could look at cholesterol levels, you could look at environmental exposures to toxins, and so forth - they could make money on it. But if something ended up being a disease of the Third World, or an application or distribution in the Third World, then we wanted the price point to be essentially at-cost. And in theory that should be a win-win solution." She floated the idea to Carol Mimura, then the director of the Office of Technology Licensing, and - after months of "back-and-forthing" between the campus and an attorney working pro bono for SSI - emerged in 2003 with Berkeley's first royalty-free license. It wasn't until earlier this year, while on a conference panel with Mimura, that she realized her "one-off" deal had set the pattern for an ongoing program of socially responsible licensing here. "She said, 'This all started with Eva,' and I was like, 'What?' I was just floored," Harris remembers. "Because there had been this life after, you know - it had really made a difference." Confirms Mimura: "It all started with Eva Harris and her hand-held diagnostic. She really was the beginning, and it's snowballed since then." - BB |

"The beauty of that was that we got a philanthropic organization to bootstrap the entire project, from basic research to translational research and all the way through clinical and regulatory affairs - that is, from bench to bedside," Mimura says. She adds that such a model is crucial when there's no "economic driver" for a commercial company, as in the case of diseases like malaria, which mainly afflict the developing world.

Diseases like AIDS, on the other hand, hit people not just in the poorest parts of the globe, but in potentially lucrative markets as well, and many new technologies may have applications in both developed and developing countries. That gives the university, which owns the intellectual-property rights to all research conducted on campus, an option it doesn't have with its anti-malarial patent: In exchange for the right to earn profits in the industrialized world, it can insist that its commercial partners make a therapy or technology available free, or at cost, in poorer countries.

Of course, it also requires the university to give up its claim to royalties on sales in those countries - something that, until fairly recently, was not an option at all.

Redefining 'value'

Berkeley's Office of Technology Licensing was established in 1990, one of many such units at U.S. universities designed to capitalize on the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act, which for the first time gave academic institutions the right to patent intellectual property - inventions, software, and other materials - and license it to private companies. That, in turn, meant the opportunity to generate royalties from sales by commercial companies of products or therapies based on that research.

The campus has since licensed hundreds of inventions, with others still in the pipeline. Many of the licenses have gone to start-ups founded by faculty members in exchange for equity holdings in the companies.

With revenues from licensing at $50 million-plus and counting, Berkeley isn't about to abandon the pursuit of commercial partnerships as a means of moving research from the lab to the marketplace. But a more expansive, socially conscious view of technology transfer has opened the door to the distribution of life-saving medicines and therapies to needy, economically strapped countries.

"In the new reality we can have a double bottom line," Mimura explains. "We can have the financial bottom line, and we can have the societal-impact bottom line. And they're equally important to us. On that basis, we can employ a full spectrum of IP-management strategies - not just the few that focus on royalty revenue."

Associate professor Eva Harris' cheap and portable hand-held diagnostic device is able to detect dengue fever in the jungles of Nicaragua. The invention prompted Berkeley's first royalty-free license in 2003. |

So excited, in fact, that the campus not only gave Harris' nonprofit, the Sustainable Sciences Institute, a royalty-free license, but used the experience to help streamline its own bureaucracy. Among other objectives, the restructuring is designed to foster more deals that expressly waive potential profits in the interest of public service. Under the old regime, responsibility for attracting research money and resources to the campus rested with one unit, the Sponsored Projects Office, while it fell to the Office of Technology Licensing to generate revenue-producing deals. Burnside brought the two units together under the umbrella of the newly formed Office of Intellectual Property and Industry Research Alliances (IPIRA), which Mimura now oversees as acting assistant vice chancellor.

"Because we're now under the same roof, the two activities are not competitive," she explains. "For instance, if we decide the best way to manage a patent or copyright is to induce research support - as opposed to trying to maximize revenue by licensing that invention, and helping a company to sell products based on it - that's a perfectly fine outcome. But in the past, if our office had that outcome, it would have affected someone else's bottom line. Under the newly organized unit, one outcome is not at the expense of the other."

The restructuring, she adds, benefits not just the developing world but the campus as well. Under IPIRA, corporate-sponsored research at Berkeley has roughly tripled, Mimura says, and foundation support has also spiked. "It's fulfilling to know that when you adopt new metrics for measuring success, and you acknowledge we're all about research and we're doing all of this in order to stimulate investment at Berkeley and get our research out for the public good, it also lowers the barrier for companies to support our work. It also reduces suspicion, and it lowers their hesitancy about giving gifts."

Despite such positive results, Berkeley's program remains the exception among university licensing offices, even within the UC system, whose principles require campuses to obtain "fair valuation" for research produced in their labs. But value, Mimura insists, is in the eye of the IP-holder.

"Under double-bottom-line concepts, societal good has a value. It's just not the same as bringing in dollars under a running royalty from a license. And it fulfills our mission of public service," she says.

"So we can, in good conscience, say that under the double-bottom-line metric of measuring not only financial return but also research stimulation and societal good, we do obtain fair value."

The world beyond the campus, it seems, is taking notice of Berkeley's - and Mimura's - leadership in royalty-free licensing. This summer, Mimura attended an international meeting on "open-source models of collaborative innovation in the life sciences" staged by the Rockefeller Foundation in Bellagio, Italy, the only representative from a university technology-transfer office.

More recently, she gave expert testimony before a state Senate committee wondering how to ensure that grants made to scientists under Proposition 71, California's stem-cell initiative, serve the dual objectives of generating revenue and providing maximum public benefits, including affordable health care for the state's poorest residents. Both Prop. 71 and Berkeley's socially responsible licensing program, she told the senators, "share an overarching sentiment that intellectual property should not constitute an impediment to research, but rather should be deployed and managed to support research, and to maximize the humanitarian impact of research."