Berkeleyan

Preserving California's history from fungi, fire, and bugs

Here's one program that doesn't want to 'mold' future generations

![]()

| 08 December 2005

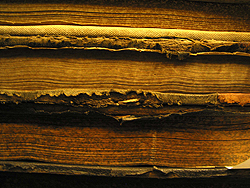

Moisture damage to archival materials is one of several misfortunes that can befall the treasures stored in the state's wide-ranging museums and historical societies. (Yolo County Archive) |

"That," it turned out, was mold. Perhaps not global-pandemic-inducing mold that would take a crack NIH team an entire episode of Medical Investigation to quash - but an alarming development, nonetheless, in the rare-documents-protection universe.

"I panicked. 'Oh, my gosh, mold!'" recalls Russell, coordinator of the county archive and records center in Woodland, where unseasonable rains alternating with scorching heat made summer 2005 a wet, hot "mold-growth heaven."

Russell immediately isolated the affected 19th-century tax assessor's lists, then donned a mask and delved deeper - into a second layer of volumes shelved behind the first. There she discovered not just garden-variety mold on a few pages of a few dozen books, as she originally thought, but scores of volumes, dating back to the 1870s, with bent covers and "1/8-inch, standing-up mold from hell."

Scary stuff - and occasion, clearly, to seek outside help.

Practical advice

Russell turned to the federally funded California Preservation Program (CPP), administered by the California State Library, whose two-day workshop on managing mold and insect invasions she happened to have taken earlier in the year.

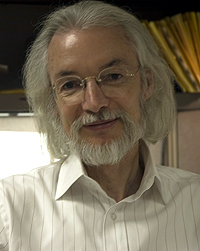

The Library's chief preservation specialist, Barclay Ogden (right), helped start the California Preservation Program, which disseminates information on protecting collections and responding to emergencies. (Cathy Cockrell photo) |

CPP answered Russell's call, providing practical advice on drying out the books, increasing air circulation where they're shelved, and regulating the humidity and temperature in the stacks. By disseminating such expertise - until now held by the state's handful of professional preservationists - "we make each institution more able to respond to its own crises," Ogden says, "as well as to avoid them in the first place."

"The Bancroft Library has a very important Californiana collection," Ogden says, "but much of the state's local history is preserved by smaller institutions. They provide a very important service, mostly without adequate funding - they're fortunate if the roof doesn't leak; it's typical not to have any form of environmental controls; the storage containers may not be archivally sound."

Indeed, a survey released this week by the conservation group Heritage Preservation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services showed that millions of rare artifacts in 3,370 museums, archives, and libraries around the country are slowly disintegrating because of poor storage, with the worst conditions found at small-town museums and historical societies.

Preservation, 24/7

Ogden's interest in book preservation goes back to his teenage years in eastern Pennsylvania, when he inherited a set of brittle family Bibles dating to the 1850s. After getting a bachelor's degree in philosophy he found a job at the Newbury Library, a private rare-book collection in Chicago, where he learned the complex and esoteric craft of saving aging books.

"There's a lot of science to it," Ogden says. "Chemistry plays a very big role, as does the history of technology, because what you're dealing with is preserving old technologies - bookmaking, leather manufacture, cloth and paper manufacture..You borrow from all over to make this field."

Through the CPP, Ogden and Mary Morganti at Berkeley, and their counterparts from 11 other California institutions (including UC Riverside, UC San Diego, and Stanford University), teach local librarians, archivists, and museum curators how to avoid and respond to common preservation threats, from mold and beetles to water damage, earthquakes, and fire. They perform risk-assessment audits of local facilities and surveys of collections; provide hands-on workshops on relevant subjects like book repair and archival-storage techniques; and operate a 24/7 toll-free number that people like Russell can call in an emergency.

"I couldn't have survived this - the collection couldn't have survived - without the preservation program," Russell says.

Yolo is one of the few counties in California that has continuous public records dating back to 1850; in many others, public records of that vintage have been lost in fires. Birth, death, court, tax, and Board of Supervisors' records are found there, as well as maps, oral-history tapes, photos, and documents pertaining to county families and businesses. The tax assessor's lists alone are invaluable for historians and genealogists, says Russell: In the late 1800s "the tax collector actually went out to the farms and made lists of their possessions: '8 pigs, 10 sheep, 2 acres of barley, a gold watch, two Spanish horses, one American horse, 2 musical instruments,'" plus a legal description of the land, which the owner then signed.

"We're small but we're unique," says Russell. "Losing our collection would be a disaster not just for our county, but for California. To have people who can step in and provide guidance in a situation like this is invaluable."

Big-picture issues

Although the CPP disseminates information on archival-quality preservation techniques, it is even more concerned with big-picture issues, such as the integrity of a building's roof and emergency-response training for staff, says Julie Page, head of the preservation department at UC San Diego and co-coordinator of the CPP. No matter how many documents you move into acid-free folders, she notes, "it takes just one fire or one flood" to wipe everything out.

Arson is the greatest threat. In 1986 the Los Angeles Public Library lost 400,000 volumes, 20 percent of its holdings, in an arson fire, the largest library fire in U.S. history. But of the hundreds of thousands of books damaged by water from fire hoses, says Page, more than 90 percent were salvaged by means of a standard preservationist technique: quickly freezing the soggy items, then slowly drying them out with vacuum freeze-drying technology.

"Big picture" preservation issues are also in play in the coastal town of Monterey, where much of the "stuff" of local history - such as photo albums and taped oral histories of land-grant families, fishermen, farm workers, cannery workers, painters, authors, and retired military people - is found at the Monterey History and Art Association (MHAA), one of the state's oldest historical societies.

Today the association owns four historic buildings, "all in need of various and sundry kinds of preservation," says Christine Capen-Frederick, the association's development director. She ticks off their liabilities: mold, a waterlogged basement, termites. "And our problems are repeated everywhere in small institutions around the state."

Capen-Frederick was at the Berkeley Public Library recently for a CPP workshop on grant-writing. She said it was her interest in education for kids that led her to her current fundraising role at the MHAA, where preservation issues are pressing: "I'm an educator who wants to use the materials in a way that serves the community, particularly kids. If a document no longer exists, how am I going to teach about it?"

The California Preservation Program is online at calpreservation.org.