Berkeleyan

Birgeneau: 'This is the marketplace that we operate in ...'

Responding to media coverage of executive compensation at UC, the chancellor speaks out about the competitive realities the system – and the Berkeley campus – must address

18 January 2006

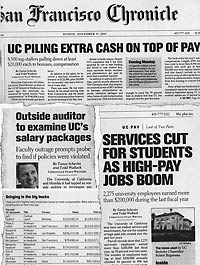

Editor's note: Last November, the San Francisco Chronicle published a series of articles on aspects of UC's compensation practices, the heart of which was the revelation that $871 million in "bonuses, administrative stipends, and other hidden compensation" had been "quietly" distributed to UC faculty and staff during 2004-05. By picking and choosing examples to highlight, the newspaper created the impression — among UC's own employees as well as legislators, opinion-makers, and the public at large — that a huge percentage of those dollars were being awarded by top administrators to each other, in a series of you-scratch-my-back-and-I'll-scratch-yours exchanges intended to elude the public gaze.

Stories in the San Francisco Chronicle about compensation of UC executives coincided with a regents' meeting at which student fees were increased and upper-level managers' raises were approved. The result: a firestorm of controversy. |

That impression was enhanced by two nearly simultaneous happenstances. First, the Chronicle had only days earlier given front-page prominence to its discovery of lapses in judgment by two top systemwide administrators: Provost (and former UC Santa Cruz chancellor) Marcie Greenwood and Vice President for Student Affairs Winston Doby, each of whom, the newspaper said, had misused their influence — Greenwood in advancing the career and compensation of a business partner, Doby in arranging for Greenwood's son to secure a paid internship at UC Merced. Second, the paper's series coincided with the November meeting of the UC Regents, at which salary increases for top system and campus administrators were approved even as a sizable increase in student fees — the fifth in as many years — was enacted.

The juxtaposition of those stories had a powerful effect on public and legislative opinion — one that UC's Office of the President (UCOP) is seeking vigorously to mitigate. In recent days it has produced a breakdown of the $871-million figure cited by the Chronicle. "While senior managers at the University have been the focus of the Chronicle's stories, these senior managers received only $7 million, or less than 1% of the $871-million figure," UCOP emphasized. The bulk of the payments were "paid to doctors and clinical faculty for treating patients and to campus faculty for additional teaching and research they do during the summer," with other payments allocated as severance to departing employees, compensation for their unused vacation time, and for other legitimate purposes.

For some time prior to releasing its breakdown of the numbers, the University — in the person of President Robert Dynes most prominently, but also in statements from members of the Board of Regents, faculty leaders, and others — maintained that compensation packages awarded to high-level administrators and faculty are justified by the intensely competitive marketplace for such talent in which UC finds itself … one populated not only by other leading public universities but by the elite "privates," whose endowments frequently allow them to tempt top talent with market-busting salaries, research funds and facilities, and the like. The essential argument is, at base, that it is UC's commitment to excellence that keeps the compensation ante high and consistently raises it higher.

As California's budget season gets under way (Gov. Schwarzenegger released his draft budget last week), the Legislature is scheduling hearings into UC's compensation practices, even as the regents and UCOP respond to calls for "transparency" by establishing oversight mechanisms, task forces, and new procedures. A lot is happening, on numerous fronts, all at once — and hence, the damage done by the Chronicle series won't be fully assessable for some time. In the meantime there is understandable concern on the Berkeley campus that public and legislative attitudes about perceived inequities within the UC system will inevitably have an impact on perceptions about this campus, the system's flagship. (Case in point: A local TV station reporting on the compensation controversy recently positioned its reporter in front of Sather Gate for visual impact, even though the substance of his report had nothing whatever to do with Berkeley.)

With information about UC's compensation practices continuing to emerge both in the press and from UCOP itself, Berkeleyan editor Jonathan King recently interviewed Chancellor Robert Birgeneau about his take on the Chronicle's investigation, the context in which he believes the questions it raises might most usefully be viewed, and the crucial issues at stake for the Berkeley campus.

Q. What was your response to the Chronicle series?

A. On the one hand, the series raises legitimate questions about whether the University system has followed its own rules, and whether those rules are fully understood and transparent. Speaking for the Berkeley campus, we welcome the UC Regents' call for transparency and accountability throughout the University of California system. You should know that we continually review and audit our administrative procedures on campus and will continue to do so.

Chancellor Birgeneau sees hope for improved staff salaries in funding flowing from UC's compact with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger (left). (Photo by Steve McConnell / UC Berkeley) |

Q. What do we find when we perform those reviews and audits?

A. The first thing I did when the Chronicle series appeared was to look at the total compensation packages in place for all of the senior administrators at Berkeley. When I did, I did not see any case where our handling of compensation for senior administrators at Berkeley wasn't entirely fair. In fact the total compensations were remarkably modest compared to those in place for similar positions at our peer institutions.

Q. And you make that judgment on the basis of …?

A. I have a clear perspective on the issues on a personal level, having been hired as president five-and-a-half years ago at the University of Toronto, and a year and a half ago here at Berkeley; prior to that I spent 25 years at MIT, eight of them as dean of science. I've gone through negotiations myself, and have hired many senior executives. As a result, I have a very good understanding of this marketplace and of the situation at the elite private universities in this country.

Q. Of course, the University of California is a public university.

A. True, but the reality of the marketplace is that the elite privates are the institutions we compete with for top academic and administrative talent, and thus the only real comparison when we look at compensation packages at Berkeley. That's a reality that was entirely lost in the Chronicle coverage — it ignored the pressures this marketplace exerts on institutions such as Berkeley.

Q. Is it fair to say that you believe there were some elements of context missing from the Chronicle's coverage?

A. Not only were there elements of context missing … in my judgment there was no context. So let me provide some. About $450 million of the $871 million is fees paid to doctors in the hospitals for their clinical work; another $150 million, approximately, represents summer salaries paid by the federal government to our faculty for their hard work doing research and teaching during the summer; $112 million represents overtime, vacation, and severance pay, performance bonuses and incentives, and the like for unionized staff. The $871-million total also includes funding for some post-doctoral fellows and graduate students. So this is a tremendous catch bag of salaries beyond those that are paid for nine months out of academic funds. Basically, the $871-million figure represents what it costs to maintain a great university system, to support the faculty and staff at a competitive level.

Q. That breakdown may well explain the situation, but for many people the issues have struck an emotional chord. Rightly or wrongly, there's a sense in some quarters that senior executives have exempted themselves from stated policies concerning compensation. What have you heard in this regard from people on campus?

A. People at Berkeley are remarkably well informed: They're sophisticated about these matters, and have a general understanding of the way the budget works.

| 'What concerns me most is the response of legislators in Sacramento who are not fully informed about what the marketplace really is in higher education.' -Chancellor Birgeneau |

Q. That said, you're taking the opportunity to speak out at this time, presumably to help clarify matters for those who don't have that understanding. What role can an individual chancellor play in speaking to these issues and controversies?

A. I don't mind saying that early on, when I first saw the articles, I thought we should come out with a public statement from Berkeley — not just a public statement but full public disclosures . . . let's just publish everything we have. However, in checking in with the Office of the President, I learned that they wanted the system to have a more coherent response. So we held off at Berkeley.

Q. Regarding the "full disclosure" you contemplated, in looking at Berkeley's numbers as carefully as you have, it sounds as if you've conducted what would amount to an informal audit of your own. Do you feel the need to commission an audit of the campus's finances?

A. There has been an audit going on for a while, conducted by the campus Audit and Advisory Services Department. I met with the auditors before the holiday break and asked them to look carefully at my own situation, as well as that of the other senior administrators. In fact, we do auditing continuously, all the time; there's nothing new here.

Q. In addition to faculty and staff, what other groups with areas of concern have you been in contact with?

A. If you ask me what concerns me most, it's the response of legislators in Sacramento who are not fully informed about what the marketplace really is in higher education. So I've spent some time personally with individual legislators and their staffs, in essence giving them the breakdown I just gave you, and that's been quite helpful. We continue to be in a very difficult budget situation, and the one thing we cannot have happen is for the state government to think that we're not using the funds they give us already wisely and parsimoniously.

Q. To help correct any such impression, President Dynes has commissioned what he terms an outside audit of UC's compensation practices — one of a number of measures he and the regents are initiating in response to calls for increased transparency. That word has gotten quite a workout in recent months: What does "transparency" mean to you?

A. It means that complete compensation information should be available publicly. For example, when a compensation package is above the threshold set by the regents, and so must be approved by them, I feel the regents should be aware of all aspects of the package.

Q. How does that jibe with your own philosophy about compensation?

A. My own philosophy is that, in general, what is available to one person ought to be available to another person, and hence it's much better to have uniform compensation policies rather than a series of separate deals that are often private. However, if we go that route, our community must understand that full disclosure will ultimately be very expensive, and it will tend to exacerbate inequalities that already exist in our faculty and leadership-team compensation packages. This might seem to be counterintuitive, but it is true.

Basically, both our senior administrators and our faculty are underpaid relative to those at our peer institutions. We spend a lot of time fending off offers to our best people from other universities, especially the privates, and we often have to go to great lengths to attract the best people here when they have competing offers from the privates. Typically, it is non-salary items that make the difference. If we have to reveal the non-salary items, especially for faculty, like housing allowances, discretionary research funds, and the like, it will only up the stakes for everyone — since, obviously, every department chair, dean, or senior administrator will demand the same benefits for the person they are trying to attract or retain. This will be very costly and, in my opinion, may ultimately work against the best interests of Berkeley. Nevertheless, if the academic community thinks that the benefits of full transparency outweigh the costs of complicating further our already fragile compensation system, then that is what we will do.

Q. But for now, you'd endorse transparency with an asterisk?

A. Yes, exactly correct.

Q. One way or another, though, people at the very top levels are being granted various perks, benefits, forms of compensation that are above and beyond salary. Whether or not the precise terms and dollar amounts in these high-level instances are fully revealed, many would argue that the larger question is why those conditions are being acceded to in the first place.

A. First of all, this is not particular to people on the administrative side. We make complicated arrangements — usually much more so — in hiring distinguished faculty than we do with administrators. The packages for administrators are generally straightforward, whereas for faculty, because they include research allowances and a range of other provisions, it is much more difficult in many cases to negotiate their total compensation. That's quite important for everyone to understand, and it's a critical part of the misrepresentation by the Chronicle that a small number of senior administrators are receiving special benefits.

Q. Can you give an example?

A. I can give you more than one. I was on the East Coast over the holiday and ran into a former Berkeley faculty member. This person was offered well over $1 million in discretionary funding for his research by an elite private university — which of course will often go to support students and postdocs as well — in addition to a 40-percent salary increase and a housing package. We simply can't meet that kind of offer, and this person was a huge loss for Berkeley.

In another instance, a faculty member being recruited by a public university was offered a $3-million discretionary research fund plus a significant increase in salary and other benefits. Thanks to some responsive donors I was able to cobble together $620,000 for this person, compared to the $3 million the public university was offering. Fortunately, this person decided to stay because he loves Berkeley. But this is the marketplace that we operate in.

Compensation on the regents' agenda

At its meeting on Wednesday and Thursday of this week at UC San Diego, the Board of Regents will be addressing a number of compensation-related items. These include:

- A proposal to create a new Special Committee on Compensation, in keeping with an announcement made at the board's November meeting by Chair Gerald Parsky. The goal, says UCOP spokesperson Paul Schwartz, is "to ensure that a dedicated regents' committee provides ongoing oversight of compensation issues."

- A discussion/overview, by the Special Committee on Compensation, of the actions UC has undertaken to review its compensation policies and practices. Regent Joanne Kozberg and former Assembly Speaker Bob Hertzberg will present an interim report on the progress of the task force they are co-chairing on UC compensation issues.

- Approval of a new overall salary-range structure for senior management positions above a certain salary level (currently $168,000). Approval will occur in public session; in closed session, the regents will approve the placement, or "slotting," of individual jobs within the salary structure they have created, taking into consideration equity issues that may arise in individual instances. "In neither case," emphasizes UCOP's Schwartz, "are salary increases being given: Senior-management positions are simply being placed into a new structure at their current salaries." (For background on this item on the regents' Wednesday agenda, see this document from the November 2005 regents meeting [PDF format]) The slotting decisions reached in closed session on Wednesday will be voted on by the full board in open session on Thursday.

Q. Where is the notion, if it in fact exists, of public service in this mix? Does it play a part in the negotiation process?

A. Absolutely. We're able to attract and hold outstanding people here at Berkeley because we're a public institution. We got a very dramatic example of that in our recent search to fill the new vice chancellor of administration position, for which the posted salary was $250,000. To come to Berkeley to ensure that our administration and business functions are managed as they should be, candidates of appropriate caliber had to be willing to take salaries that were half or less what they would make at the elite private universities, let alone in the private sector. We nonetheless ended up with several outstanding candidates whose salaries were factors of three or four or more larger than the one we were offering. These outstanding people were willing to come here completely and entirely because of their commitment to public service.

Q. Public service and other altruistic motivations notwithstanding, the clear message is that the university must pay competitively to attract top talent in a variety of functional areas. That said, many workers say that their salaries are so far below competitive ranges that it would take years of adjustments to bring them up to parity. They say the implication is clear: Competitiveness is a metric in use at the very top ranges, but everybody else is on their own.

A. I think that's unfair. I've sat through, in several regents meetings, the comparisons from the bottom to the top, and we've looked at that carefully at the Council of Chancellors meetings as well. First of all, we need a scale here: At the very top — for chancellors and provosts, vice chancellors of administration — our salaries are typically one third to one half lower than those at the institutions we compete with. The salary gap for people at the lower levels is about 18 percent. That's their take-home pay, exclusive of the benefits package. The benefits package at UC is so much better than that at other California employers that it largely compensates for the 18 percent. So if you look at the total package, our clerical workers are paid at approximately market rate.

Now, is that satisfactory? The answer is no — we should do better. Most importantly, there are people who receive egregiously low salaries, and that's an important issue that we need to address in the near future.

Q. How might we do that?

A. The hope is that with progressively improving funding from the state under the compact with Gov. Schwarzenegger — and, in the case of Berkeley, after what we hope will be a successful capital campaign in the years just ahead — we'll have increased resources that will enable us to bridge the gap for people who are trying to survive in the Bay Area on unfortunately low levels of income.

Q. You cited the compact with the governor as an element in improving the salary situation for employees. Do you have a sense or a concern that the political blowback from the compensation controversy might have a bearing on the compact going forward?

A. The governor has assured us that he's committed to the compact. The focus of our concern should be on key people in Sacramento not understanding what the real numbers are. In my opinion, the San Francisco Chronicle has not been helpful on that front.

The Berkeleyan welcomes your feedback; write to berkeleyan@berkeley.edu