Berkeleyan

Jarralynne Agee does 'the Po thing'

CALS Project manager's 'urban drama' is staged in Bronson's new Random House release

![]()

| 02 February 2006

HR staffer Agee's life journey has been shared with a wide audience since seeing print last fall. (Deborah Stalford photo) |

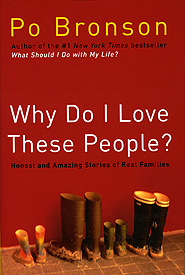

Human Resources analyst Jarralynne Fletcher Agee is at pains to explain how her story, and that of her family, made it into the new Po Bronson book, Why Do I Love These People? Odds were against it. The popular writer interviewed some 700 other people for this latest project, on the adversities and triumphs of family life - but included, in the end, just 19 stories.

The book's publication in November has brought a fair share of notoriety to Agee and her mother. They've posed in the living room for the November-December issue of AARP: The Magazine (which calls itself "the world's largest-circulation magazine"), and references to their story turn up in book reviews published around the world. (The New York Times wrote of "an African-American clan strained but not separated by a mother's mental illness.")

A "psychologist, literary strategist, and writer," as she bills herself on her personal website, Agee is not averse, in principle, to ink or stage lights. She has an essay in the 2004 anthology Chicken Soup for the African American Soul and does "a fantastic presentation," she's not shy to say, of that piece for public readings. As a Fisk University undergrad and a grad student at Ohio State, she studied theater as well as psychology; while earning her doctorate at the California School of Professional Psychology, she performed stand-up routines about her childhood in local comedy clubs. There's a memoir in the works and an upcoming appearance, in her role as psychologist, in a Court TV documentary.

But inclusion in Bronson's book, subtitled Honest and Amazing Stories of Real Families, takes self-disclosure, for Agee, to a new level - shining a bright light on the "stark, hard side" of her personal and family past. The process began in 2003, when she stumbled upon Bronson's website and responded by e-mail to an idea he floated there, for a research project on families and resilience. It wasn't long before Bronson arrived on her doorstep, tape recorder in hand.

"You talk about hesitation! I decided I was going to lie to him. I didn't mind telling my story," she recalls, but planned to share "just enough of my urban drama to fill his notepad," without revealing its grittier details. "In the black community, you don't air the dirty laundry in public, you never speak ill about your momma, and you don't invite some guy into your front room and tell him everything!"

Momma, however, had her own ideas. Bronson "came and sat on mom's floor" - and Karen, confined to her bed, proceeded to speak the family business into his microphone for three hours. "She told him everything," Agee recalls, including stories she herself had never heard before. In the months of interviews that followed, they argued more than once over "the Po thing" and how much to tell the world.

'Even the crazy stuff'

|

When publication day arrived, Agee read Bronson's treatment of their lives for the first time. In a chapter titled "Dorothy's Child," he retells the story of Karen Fletcher (daughter of Dorothy) of Dayton, Ohio, and her three children, of Karen's cunning and sometimes disturbing strategies for feeding Jarralynne and her siblings and keeping the family together, despite her undiagnosed mental-health issues and the hardships of poverty. ("One of my mother's constant prayers," Agee says, "was 'Lord help me or take me tonight.' And one of my prayers, from the time I can remember, was 'Help my mother or take her tonight. Because this is too much.'")

"Dorothy's Child" follows mother and daughter through years of estrangement to the present decade, when Karen suffered a disabling stroke and Jarralynne and her husband, Bob Agee (a sports-medicine physician at Kaiser, team doctor for the Cal rugby squad, and assistant medical director for NFL Europe), decided to put up Karen and her husband, Gene, in California.

"I wanted to cast my mother off, to just go and experience my successes," Agee says. But in recent years, "it had begun to hit me that I can't feel really proud about everything I've done without acknowledging what she did. Even the crazy stuff. Even her begging for food to feed me. Even her Ohio Bell.."

The latter refers not to Karen's job per se (she worked as an operator at Ohio Bell) but the role she played in the Dayton black community, helping friends and neighbors in a pinch. "If people's lights were going to get cut off, or they were going to get evicted, she could make phone calls and help these people," Agee recalls. Because of her middle-class roots, Karen knew how to navigate in the world and how to switch to a white voice, "the King's English," Agee says. She used these skills to make payment arrangements on the phone for a neighbor, persuade a judge to keep a kid out of jail, or urge a college-admissions officer to admit a talented student. Dozens of black children from the neighborhood went to college thanks to her mother's intervention, Agee recalls.

A voice for the voiceless

Since 2003, Agee has headed the CALS Project, the campus's workforce-literacy program, which provides free tutoring in English for Berkeley staff and supports their career mobility. Initially hesitant to accept the assignment, Agee has since come to recognize that in that role she's "helping people have a voice," much as her mother did in her community. "As I've witnessed in my own life, sometimes people can't be advocates for themselves. If they can't speak or read the language, talk the talk, they're out of the game from jump.. I feel like I'm doing what my mother did in Dayton."

Book events Links to the CALS Project and her African American psychology class, are on Agee's campus website . |

Agee teaches an undergraduate course, Issues in African American Psychology, whose main theme is indicated by the question - rhetorical and, for Agee, deeply personal as well - "Why doesn't Momma get help?" African Americans, she notes, "are twice as likely to have a mental-health diagnosis, but we're the population least likely to get routine mental-health care."

Lack of access is one explanation. "For black people," she says, "you go to jail and that's how you get a therapist; you land in the foster-care system and then you get assigned a social worker. Or you get AIDS, and then you get a caseworker. But we don't typically get to elect mental-health services."

When those services are available, she notes, African Americans can be reluctant to use them, as they're often in an adversarial relationship with social-service agencies. Her mother, for one, feared that her children would be taken from her if she revealed the full extent of her depression or poverty to a social worker or a schoolteacher. Instead, like many of her peers, she "suffered through."

"Accessing mental health care is not a tradition in our community, but it needs to be," says Agee. "A dash of Zoloft would have helped my mother 25 years ago."

'It's not just me'

Telling all in a Random House tome has had unanticipated benefits for Agee. One has been that people from all walks of life, on and off the campus, now approach her to share their own stories of family struggles and mentally challenged relatives. "Feeling like you're the only one who grew up with a momma who was depressed, the only one who had to send money home, is an oppressive and crushing feeling," Agee says. "Po's book is liberating: It's shown me that it's not just me, or black people, or the poor; a lot of people out there struggle with having it all but not having it all together." She speaks of "a past that we are constantly trying to run from and never look back at. Po has helped me see it's okay to look back and still move forward."

All this has reignited Agee's ambition to finish her book-in-progress on her relationship with her mother - resisting again the temptation to keep her story to herself. "On the one hand," she muses, "it's the same old ghetto story, the same old 'black kid does good.' But even if that story has been told 500 times, it needs to be told 501 times. 'Black girl does good and then both she and her mother survive' is the story I want to tell."

Agee takes inspiration from Stephen Hinshaw, chair of psychology, who wrote about his father's struggle with bipolar disorder in the 2002 book The Years of Silence Are Past. "If he could share his story about his father's misdiagnosis, I feel liberated to share the story of me and my mother. Hopefully people will use it as a catalyst to share what's true for them."

Now 36 and the parent of two young boys, Agee says she "always wanted to live long enough to forgive my mother, for all the days we were hungry, worried, or scared. But ultimately I want to forgive myself for being mad at her for so long. That's really letting it go."