Berkeleyan

|

The misguided taking of Monterey (war had not in fact been declared) by the U.S. sloop Cyane was rendered by crew member and amateur artist William H. Meyers. (Meyers, William, b. 1815, The Taking of Monterey, 1842; watercolor and ink on paper; William H. Meyers' Journal,The Bancroft Library) |

If the Bancroft caught fire, what would you save?

Planning the library's centennial exhibition forced curators to make difficult choices: Marshall's nugget, or a stunning edition of Chaucer? The selected items go on view at the Berkeley Art Museum this weekend

![]()

| 08 February 2006

In 1905 the University of California purchased historian Hubert Howe Bancroft's personal library - a "massive accumulation of books and manuscripts," as its caretakers describe it today. But it was not until early May 1906, following the earthquake and fire of April 18, that its contents were ferried across the bay to Berkeley. Fortuitously, the Bancroft Library, then located on Valencia Street in San Francisco, was the only library of any note that did not burn to the ground during the disaster.

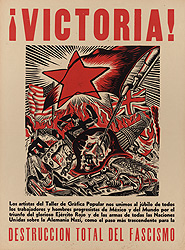

This poster, from the Bancroft's Taller de Grafica Popular collection, is among the items that made the curators' cut when the centennial exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum was being planned. (Victoria! Destruccion Total Del Fascismo, Taller de Grafica Popular collection,The Bancroft Library ) |

The Bancroft Library Centennial celebrates not only the survival of the core collections and their arrival on campus but the library's evolution as the busiest and most-accessible special-collections library in the country. Two major events are planned to mark our centennial year: an exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum, which will open on Feb. 11 and run through Dec. 10, and a symposium, which will be held concurrently with the opening of the exhibition.

The challenge we curators have set for ourselves is to create an exhibition that highlights some of the Bancroft's treasures and incorporates all the components of the Bancroft collections into a coherent exhibition that not only articulates the library's distinguished past but also envisions its future.

While discussions regarding the centennial had been underway for about two years, our collective focus was on the move out of the Doe Annex and its renovation. [See "How do you move a rare-books collection?," Berkeleyan, Aug. 25, 2005.] And although the choice of the Berkeley Art Museum as the exhibition venue seemed perfectly appropriate to us, museum exhibitions are often planned and gallery spaces scheduled five years in advance. The timing on both fronts was not optimal: Gallery space was restricted, and choosing a handful of exhibition items - 100 to 200 objects from millions to represent a century of collecting and growth - felt akin to asking parents to choose their favorites from among their children. Nor did imagining the library in flames and asking what each curator would rescue bring much comfort or provide much guidance.

How to choose from the cornucopia that is Bancroft? To begin with, the curators drew up lists of manuscripts, books, maps, photographs, paintings, objects, and rarities that they thought should be included in the exhibition. The initial lists were exhaustive, the constraints of time and space daunting.

Some choices were obvious. Such seldom-seen objects as the Codex Fernández Leal, perhaps the most valuable item in the Bancroft collection, will be on display. Produced in the mid-16th century, although possibly based on a pre-Columbian predecessor, this codex is a pictographic, double-sided scroll almost 10 feet long and written on native amatl fiber paper; it describes warfare, conquest, and sacrificial ceremonies in the local region of the Cuicatec, a small indigenous culture in what is now the state of Oaxaca. The "Wimmer" gold nugget, the one that was found by James Marshall and set off the California Gold Rush, is well-known to the users of the Bancroft but much less so to the broader public. The Breen Diary, written by a survivor of the ill-fated Donner party, the earliest known drawings of San Francisco and the Yosemite Valley, the first photograph of Mark Twain, as well as a rare volume from the first publication of the complete works of Giovanni Baptista Piranesi will also be part of the Centennial Exhibition.

Some choices were less obvious. For instance, Theresa Salazar, curator of the Western Americana collection, chose her "single-most-favorite piece of ephemera in the whole collection," which she found among the Bancroft's cartons of Sierra Club records. It is a paper Dial-a-Wheel about the euphemistically named "Upper Colorado River Storage Project." In the mid-1950s, the "Aqualantes" (water vigilantes) who created the wheel intended users to spin it and learn the many benefits of damming the Colorado River. Spinning the wheel now teaches us about an era that held an uncomplicated belief in man's rightful dominance over nature.

Other choices emphasized the synergies that the collection offers researchers: Manuscript pages from Frank Norris's 1899 novel McTeague could be shown with a brooding portrait of the author by I. W. Taber, as well as with a scrapbook from the filming of Greed, Eric von Stroheim's cinematic masterpiece based on the Norris work. From the History of Science and Technology Collection, curator David Farrell chose both a manuscript copy of Euclid's Elementa Geometriae from 1460, the words copied by a long-ago hand with surpassing delicacy, and a first edition of the printed version (1482), while nearby, the first printed Periodic Table (by Dimitry Mendeleev in 1869) could mark the rise of modern science.

Some items were eliminated for conservation reasons. Photographs and other works on paper cannot be exposed to light for long, so many of those objects would have had to be removed from display halfway through the run of the show and replaced with other items. But even with that precautionary step, some objects were deemed too fragile. George Fardon's album of salt prints of early San Francisco - one of only seven complete copies extant - was regretfully removed. Other decisions to cut items were based on favoring things never seen over those "stars" that have already had their share of the limelight. Thus, rare-books curator Tony Bliss decided not to show the stunning Kelmscott Press Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. But he sighed and struck it from the list while paraphrasing Leonard Bernstein (who said, "It brings me great joy to know that every day 100,000 people are born who have never heard Beethoven").

When the Bancroft Library reopens in its renovated quarters, it will have a state-of-the-art gallery many times bigger than its previous display space. Then, those treasures that did not find their way into this show will have their day. In the meantime, visitors to The Bancroft Library at 100: A Celebration 1906-2006 will find a striking array of books, letters, and works of art - the tip of a culturally rich, historically vital, and visually compelling iceberg.

This article is reprinted with permission from the Spring 2006 issue of Bancroftiana, the newsletter of the Friends of the Bancroft Library. Jack von Euw is curator of the Bancroft's pictorial collection; Isabel Breskin is assistant curator of the Bancroft's Centennial Exhibition.

The Bancroft Centennial Symposium will be held Friday and Saturday, Feb. 10 and 11, at the Berkeley Art Museum. Speakers include Kathleen Cleaver, Michael McClure, Kevin Starr, Robert Hass, and numerous other scholars and topical authorities. The symposium program is online at bancroft.berkeley.edu/events/program.pdf.