Berkeleyan

An improbable Catholic

Upcoming 'Lunch Poems' reader Mary Karr finds reverence and dread in poetry, memoir, and prayer

![]()

| 15 February 2006

Though an unlikely candidate for baptism, Mary Karr, at age 40, took the plunge.

"If I had been able to stay sober, I would have never prayed," says the renowned poet and memoirist, whose account of her rough-and-tumble East Texas childhood, The Liars' Club (1995), became a bestseller. Instead - on the suggestion of a poet friend and ex-drinker - she took a spiritual test-drive: she got down on her knees each day for a month, praying to stay dry.

Writing poetry, says Mary Karr, is "a great privilege." (Marion Ettlinger photo) |

"I kept trying to quit drinking and I would start again," she admits. "Only through praying could I stay quit." She had her last drink 16 years ago, and since then she has made the leap from agnosticism to the Catholic Church, a move that didn't go down easy with her friends.

"I was completely mocked by them," she says. After her baptism, Karr received a postcard from her friend, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Ford, that read: "Not you on the Pope's team. Say it ain't so!"

Karr, a professor of English at Syracuse University, will be reading her work at Lunch Poems on Thursday, March 2, 12:10 p.m. in the Morrison Library in Doe Library. The Berkeleyan spoke to her by phone about poetry, memoir writing, and her hard-won faith.

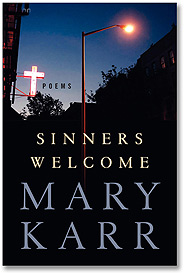

Karr details her religious journey in "Facing Altars: Poetry and Prayer," the afterword in her most recent collection of poems, Sinners Welcome (Harper Collins, 2006). She writes: "Poetry never left me stranded, and as an atheist most of my life, I presumed its comforts were a highbrow, intellectual version of what religion did for those more gullible believers in my midst - dumb bunnies to a one, the faithful seemed to me, till I became one."

|

Karr finds both poetry and prayer "very humbling." When engaged in writing a poem or in praying, she has a "sense of awe and reverence" while also being in "a state of terror and dread."

When Karr's son was young and her faith was still new, they used to go to the county fair in Oswego, near Syracuse in upstate New York. Karr describes the other patrons at the fair as "hideous, bloated, greedy, and stupid."

On the bumper cars, where everyone acted out their aggressions, her fellow fairgoers' terror seemed familiar to Karr, a response she labels as counterintuitive. "Instead of getting in the bumper car and thinking 'it's really awful that people want to knock into you and send you crashing into the wall,' there was something about doing that that bound me to them."

In her early years she experienced a similar commonality reading poetry and novels, where initially she "felt bound to the writer" and then to other people who talked about their experience reading the work. Later, as a graduate student at Goddard College, Karr's teacher, poet Robert Hass (today on the Berkeley English faculty), spoke about reading poetry as "eucharistic," a notion she echoes today. "When I read poetry, I take someone's feeling into my body. If it's the real thing, it is in fact the body of God, and it changes me. It's always so amazing. There are certain poets you read - [Czeslaw] Milosz being one - you read those poems, you lift your head, and the world is completely altered." Never mind, she says, that "nothing's happened," that there are still bills to be paid and laundry to fold.

Karr now has a similar sense of wonder about the Catholic Church, an institution she once viewed as "fraught with bogusness and horse dookie." Whereas she had long thought of churchgoers as "sheeplike," instead she found a group of socially engaged activists who regularly protested at nuclear-reactor sites and lent a hand to people from El Salvador. "They didn't do it with this kind of maudlin, church lady, grotesque piety," explains Karr. "There was nothing drippy or wet about it. It seemed to me very energized and realistic - you're painting a house for people, it's hot, it's a pain in the ass and we'd sooner quit and drink beer all day, but this needs to get done."

That sort of sensibility jibes with Karr's own sense of herself as a "cafeteria Catholic," one who believes that priests should be permitted to marry ("I think the reason they forbid this is the cost of the wife and children") and women should be allowed to be priests. Karr, who has been a feminist since she was 12 years old, is also pro-choice.

Besides the hard time she's gotten from friends, the most difficult part about converting to Catholicism "was admitting that what I was able to figure out at home about how the universe ran was limited. I really realized that I didn't know and I couldn't know anything." When Karr first joined the church, she viewed the resurrection metaphorically. "I loved the idea," she says. "You can think about it in pagan terms as the fertility myth - a person dies and is reborn."

But then one of Karr's church pals, a Franciscan nun, asked her if she thought the resurrection was a hoax. When Karr said that's just what she thought, the nun took her to task, explaining that in the religion's early days "nothing good socially came of being a Christian. Peter was crucified - allegedly upside down; it wasn't fun." The nun told Karr it was not advantageous for the Christians to promote the idea of resurrection; rather it was analogous to South African blacks "supporting Mandela during apartheid."

Karr dug deeper, entertaining the idea that "maybe then they were all nuts engaged in some collective hallucination." But then she read the writings of Paul, whose words she characterizes as "educated" and whose arguments seem "really clear, not at all insane." So Karr found herself in a place of not knowing, one she says was much less comfortable than dismissing the resurrection as "a bunch of horseshit. I realized what my investment was in terms of intellectual pride and a sense of myself as 'smart,'" she admits. "All my professors didn't believe, all the people I went to college with didn't believe, all the poets I know didn't believe.

"It occurred to me there was as much social pressure on me not to believe as there was on people in the Salem witch trials." Then she corrects herself. "Well, not quite to that extent. No one's going to set my hair on fire."

Mercy, mercy, mercy

Since coming to prayer, Karr says she's changed as a person both "absolutely and not at all." She says that she has to apologize a lot more. "Left to my own devices, I don't think I'm a particularly nice person. I spend a lot of time in fear, and fear is the enemy of beauty and love." She still feels amazed that prayer and faith came to her as a practice. "Faith wasn't something that you felt," she explains, but a ritual in which to engage.

When Karr was baptized, the priest told her she was lucky she had waited till she was 40, since she had gotten to do her sinning, and now it would be wiped clean. She asked him, "What if I don't believe that?"

He answered it was her job to believe it was so. "Even if you didn't believe in baptism, what if you did believe all your sins were forgiven or at least felt obligated to act as if they were?" wonders Karr. "Powerful idea, mercy, isn't it?"

These days Karr could use some of that mercy, since she's hard at work on her third memoir, Lit. (Her second, Cherry, was published in 2000.) She admits memoir-writing always gives her "an enormous, chewing anxiety. It's never a happy thing." Karr has talked to other writers who have tackled the genre and she reveals they all experience a similar phenomenon. "It's just really hard. I never think about writing a memoir without being flooded with dread, partly because of all the moral difficulties it poses. You have to be really scrupulous and still you're going to fail."

The topic of memoir-writing leads to James Frey, who created some remarkable fictions in his "memoir" A Million Little Pieces. Along with Oprah Winfrey, who had selected Frey's memoir for her book club, Karr was called in as a pundit to comment on the deception. Karr was quoted as saying that the fact that Frey fabricated key events in his memoir "called into question every aspect of this guy - who he is and every damn aspect of his book."

Ironically, like Frey, who originally shopped A Million Little Pieces around as a novel before 19 rejections and a publisher's suggestion convinced him to market it as a memoir, Karr first tried to write The Liars' Club as fiction. "The things I made up always cast me into such a good light. I made up details so that I would sound noble and wise." She calls the result "terrible." Instead, she set to work on a task she had laid out for herself at age 10 "to write one-half poetry and one-half autobiography."

Perhaps Karr finds Frey's lying so difficult to stomach because she puts herself through hell when she's writing about her own life. Last fall, when she began working on Lit, she set herself the task of writing six hours a day or until she reached 250 words. After two-and-a-half weeks and much writing and more deleting, she had penned only 600 words.

Karr's editor asked why the going was so rough, and she answered, "I just write shit that's not true. I'm writing it and thinking the whole time, 'This is such horseshit.' I can feel it. I can just sense it. It feels not true, but it's all that I can remember."