Berkeleyan

Sister Helen Prejean (Deborah Stalford photos) |

Helen Prejean brings her sister act to Berkeley

The renowned author-activist, a consummate speaker and storyteller, urges her campus audience to engage in deeper reflection on capital punishment and the 'machinery of death'

![]()

| 01 March 2006

Some people can write and some can speak in public. Sister Helen Prejean can do both, and last Thursday evening the renowned nun, writer, and anti-death-penalty activist addressed an audience of more than 300 in the campus's Chan Shun Auditorium. Her lecture was sponsored by the Ron Dellums Lecture Series of International and Area Studies' Peace and Conflict Studies program. IAS Associate Dean Ananya Roy introduced Prejean and presented her with the Chancellor's Distin-guished Honor Award "in recognition of many years of visionary activism."

Originally from Baton Rouge, La. - where she has temporarily relocated from New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina - Prejean delivers her compelling message with a storyteller's flair. Her anecdotes (often repeated in lectures, interviews, and her own writings) are punctuated by impeccable timing, comic one-liners, and descents into a low register when good ol' boys enter a tale. She began her campus talk by describing her encounter earlier in the day, at a reception with Peace and Conflict Studies students, with Iraq war opponent Cindy Sheehan - and their conversation on how each was propelled into action. One could see that this encounter with Sheehan at Berkeley had just entered Prejean's repertoire, and was likely to be told and retold on the national lecture circuit, where she spends much of her time.

How to remain on message day after day yet stay fresh, and wear a public persona but be able to take it off, are challenges of such a life. Prejean, 66, is often asked about the rigors of her travel schedule; she told her campus audience (and, earlier, her Berkeleyan interviewer) that as an activist she is "quickened," not emptied, by her exchanges with strangers.

The Berkeleyan spoke with Prejean between her afternoon reception and evening talk, which in turn were sandwiched between Bay Area appearances at the Commonwealth Club, Cody's Books, Temple Emanu-El, and Grace Cathedral.

In Dead Man Walking you told the story of how you got involved as a spiritual counselor on death row. And that led to an entirely different life - campaigning against the death penalty, being on the road, doing something like 150 lectures a year.

The first person I accompanied to death, Patrick Sonnier, he was executed in the electric chair. I came out afterwards (it was the middle of the night) and threw up. And I remember thinking,"I've been a witness. Everybody's sleeping; everybody thinks this is a great idea, but I know it's not a great idea!" There in the dark, I realized, "I gotta tell the story." It was not even a choice. So I began speaking, and that led me to write Dead Man Walking, and then my second book, The Death of Innocents.

To unleash energy, or to capture it, is what the spiritual life is about. People say to me, "Oh, sister, you must be so exhausted." They say that about traveling. For me, traveling is having some time for peace and quiet. You don't have anybody calling you; you have your little section in the plane, your little cloister. I never talk on a plane; I never say who I am.

You're here in California as the death penalty is on the front page. No matter where one stands on the issue, the Michael Morales case is rife with contradictions: the extreme care taken to assure that someone who admits to a brutal, painful murder be put away without pain; asking members of the medical profession, sworn to protect life, to participate in ending a life. What, in your mind, does the current controversy reveal about the practice of capital punishment in the U.S.?

There has been a quest to make the killing of human beings "humane." We used to have hanging, then the electric chair, and now lethal injection. Now here's the interesting thing about lethal injection: they use three drugs. Sodium pentathol for people to go to sleep. Short-acting. Remember that, 'cause that's just what precipitated this thing in California. The second drug is pancuronium bromide; its sole purpose is to paralyze the person. The third one, potassium chloride, is what kills the person; it throws them into cardiac arrest.

| To listen to Sister Helen Prejean online, go to moratoriumcampaign.org and scroll down to the blue box in the center of the page. To learn about Tim Robbins' stage-play version of Dead Man Walking, being made available for college and university performance, see dmwplay.org or e-mail Playproject @earthlink.net. |

You really can kill a person with the first drug and the third drug. Why do you have that second drug? The sole reason is so the witnesses (it's almost a secret ritual, there may be 10, 12 people witnessing an execution) do not see the person writhe as they're thrown into cardiac arrest. You can't lift a finger; you can't cry out; you can't move your lips; you can't open your eyelids. So they've begun to have hearings about that second drug and what its purpose is. Veterinarians are testifying that they don't use it when they euthanize animals, because you can't hear if an animal is in distress. They're raising the question of what's the cocktail? Why are you using that second drug?

There have been cases where lethal injections have gone awry: difficulties finding a vein, IV catheters clogging to prolong the person's death.

Yes. And it came to light that the barbiturate part is very short-acting. If anything's going wrong, there's no way for them [to assure that the prisoner dies painlessly] - that's what precipitated the current situation; a trial judge looked at it and said, "We need to have a longer-acting sleeping agent." Which means it needs to be administered by an anesthesiologist. And they balked at doing it.

So they keep trying to finesse this death, to mask the death and say, "We're really not killing anybody and we want it to be bloodless." I mean, they even put alcohol on the person's arm when they're injecting them. Germ-free death! But you can only mask and mask and mask so much.

They just come into more and more complications. So, good! Any complication in the machinery of death can help the American public go deeper into reflection on what's this thing about.

The Morales execution is on hold for now. But before this, we had two executions at San Quentin in as many months.

Yes, though your state has over 600 people on death row, and you've killed 13 people in almost 30 years. Something in you is not very serious about the death penalty; you are not a real practitioner. The real executioners, the practitioners, are the 10 Southern states that practiced slavery, 'cause we've done over 80 percent of the executions.

Which raises constitutional questions.

Yes. It says "Equal Justice Under Law" on the Supreme Court building. Yet less than 1 percent of all executions are done in the Northeast; very few are done in the West. That regional disparity, isn't that a matter to give us pause? Do some people have different constitutions, different guidelines?

When the Supreme Court overturned the death penalty in '72 [in Furman v. Georgia], it was because the death penalty was arbitrarily and capriciously applied. The court said, "You can't tell from the description of the murder which ones would get the death penalty and which ones won't." Well, guess what? It's still the same way! What we see in practice, if it's in the South, if you killed a white victim - those things add up to make it a lethal lottery.

The Supreme Court is partly responsible for the impasse: they've given criteria that nobody knows how to follow. Imagine now, they say, "The death penalty is not for ordinary murders. [In a Southern accent:] Not your garden-variety type murder. Just the worst of the worst." And nobody knows what "the worst of the worst" is. In practice it sure seems that "the worst of the worst" is if you kill a white person. That seems to be the opening requirement, entry level. Because 87 percent of the 1,000-plus people who have been executed [since Gregg v. Georgia, 1976, in which the Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty] killed white people. Whereas when people of color are killed, that doesn't even seem to cause a blip on the screen.

So arbitrariness of application begins at the very front end of the process, the charging end.

That's right. Politics drives it, because you have an easy political symbol. People run for office, how do you show you're tough on crime? You say you're for the death penalty. And you can have one prosecutor in one county who goes for the death penalty every time he or she has the opportunity. And right next door, somebody who never goes for it at all. So to make the system go, you have huge discretionary power in the hands of DAs, who all have different agendas and reasons for going for the death penalty or not.

And then you have the tremendous cost [of each capital case]. New York State, when they put it down, they had practiced it for nine years, they had four people on death row and it had cost them over $180 million.

You've worked with victims' families as well as prisoners on the row. What would you say to a relative of a murder victim who wants to see the murderer executed to attain a sense of justice?

They're understandable. They live in a culture where they have lost a loved one to violence and have been told by authorities in the culture, "We're going to honor your dead loved one by seeking the ultimate punishment; this is how we're going to honor them." To put it conversely, it's like saying, "Not to seek the death penalty means we're dishonoring your child." Victims' families are so vulnerable, and so confused, and so emotionally on a rollercoaster.

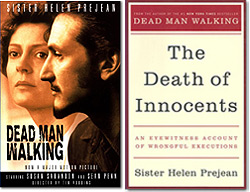

Academy Award voters were so impressed by Susan Sarandon's portrayal of Helen Prejean that they gave her the 1996 Oscar for Best Actress. The film was also nominated for Best Actor (Sean Penn), Best Director (Tim Robbins), and Best Original Song (Bruce Springsteen). At right, Prejean's new book, The Death of Innocents. |

With the Morales case, I read in the paper, the mother of the young girl who was killed said "I've been waiting for this execution for 25 years. And now you're trying to say, 'You're causing him too much pain'!? Look at the pain my daughter felt!" As if you can ever equalize the pain: they killed, so they shouldn't be alive; they caused pain, we ought to cause them pain.

But I dedicate The Death of Innocents to Murder Victims Families for Human Rights [whose members oppose the death penalty]. These are people who choose not to buy into that "equal justice" notion. They say, "The death penalty re-victimizes us." Murder victims' families are told, "Now you wait all this time, and then we'll summon you, and you get to witness as we kill the one who killed your loved one." It's so manipulative; it's using them.

You write in both your books about relatives of murder victims who have come to oppose capital punishment.

Bud Welch - he put it well. His daughter Julie was killed in the Oklahoma City bombing. He said, "By the time it came to the death of Timothy McVeigh, six years later, most of the victims' families had figured out that whether Timothy McVeigh was killed and they got to watch it over a little closed-circuit TV, or he got 168 life sentences - whatever happened to Timothy McVeigh, they still had to deal with the empty chair. And that it was a diversionary tactic, it was illusory, to think that by watching him die they were going to come back and find the chair less empty. He said that over half of them had figured that out, and chose not to watch the execution.

You've talked about two abolitionist movements - one to abolish slavery and now to abolish the death penalty - and the connections between capital punishment and the history of slavery, and racism, in the U.S. That's not talk one expects from a middle-class white woman born in the 1930s in Baton Rouge.

Right, with African Americans as my servants, growing up as a kid, segregated.

I assume these ideas have evolved over time, but were there key moments that contributed to your growing understanding of race? Could you take us inside one of those experiences?

It was an awakening that the gospel of Jesus is about being with the underdog, and being with the voiceless ones. It was at the time in New Orleans that I moved from the Lakefront into the St.Thomas housing projects, and began to see the other America. And experiencing the great American Dream - you know how we usually see the front part of the tapestry? - from the back side, where the threads are cut, and there are holes. Seeing people beaten up by the police, public schools where you couldn't even read when you graduated, people forced to raise their families in these nesting places of violence and drugs. Just unspeakable! And it's hidden from our eyes!

One gift of Katrina is that for a brief moment the veil was pulled aside on the people left in that Superdome. How do you have an evacuation plan for a city that does not account for 150,000 people without cars? Well, the same way you let them die [on a daily basis]. There's more than one way to drown in a society. Poverty drowns you.

How long did you work in the St. Thomas housing projects?

Four years. It's because I was in that soil that I got involved in opposing the death penalty; it would not have happened if I had stayed out by the lakefront - which happens in America all the time! We have these separate Americas and because people have cars, and the transportation, and the way cities are organized, people don't go into the inner city; people are very scared of poor people. So we stay away from each other.

Was this when you began to write? Did it come out of seeing, as you put it, the tapestry from the back side?

What happened was I began to have a passion, like, "I can't walk away from this! Look at this!" And that's really when I learned how to write. Dorothy Day had started these Catholic Worker houses, and I said, "We need to start us a little newspaper here; we need to put faces on the people. 'Look, this is a real person.'" 'Cause people say, "All these welfare people, they don't want to get off of welfare; they could go get a job." So we started a newspaper called Flambeau: A Catholic Voice for Justice, and that's when I learned journalistic techniques. I worked with Jim Hodge from the Times Picayune; he taught me writing. I started reading books about writing. So when I went to do Dead Man Walking, I knew how to write.

Eventually Susan Sarandon read that book and approached you about making it into a film. How has that changed your life?

Before that I was lucky to get three people to come hear me talk. Since the movie, it packs them in. A lot of times it's curiosity, university kids - "Let's go see the real nun played by Susan Sarandon." Because of the film, I get a lot of invitations. It means that you do a lot of work.

Inner contemplation, silence, was part of your initial experience as a nun. How do you deal now with the tension between fame and a need for solitude?

You got to balance your own life; each one of us has to be the balancer of our own life. All that fame means for a nun is more work. You don't see a lot of material benefits; it goes to the community and the work. It's not like I'm going to the Bahamas on it.

But for me the big thing is to get the word out there. When I sat at the Academy Awards [where Susan Sarandon won an Oscar for her portrayal of Prejean], and 1.3 billion people in the world were watching and the story was given over the world, I rejoiced. Because I knew that more people would reflect and go deeper on the death penalty, people will go deeper into our own hearts. We're bumbling, frail, human beings - and this system doesn't work any better than our levee board in New Orleans does to keep a hurricane out.