Berkeleyan

|

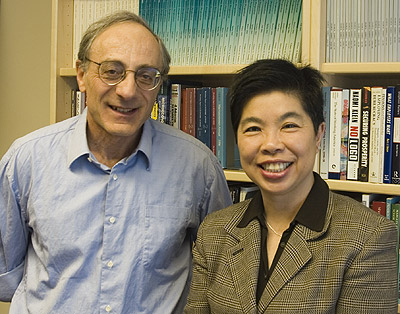

Michael Reich directs the campus Institute of Industrial Relations; Katie Quan chairs the IIR's primary outreach program, the Center for Labor Research and Education. Both believe politics are behind the institute's ongoing funding woes. (Deborah Stalford photo) |

For UC labor studies, marketplace of ideas lacks a safety net

Governor's 'zeroing out' of multi-campus research program with ties to unions prompts charges of politically motivated 'reaching in' to university's domain

![]()

| 22 March 2006

In an exultant letter to supporters in the fall of 2000, business professor James Lincoln, then-director of Berkeley's 55-year-old Institute of Industrial Relations, trumpeted the news that the 2000-01 state budget, just signed into law by Gov. Gray Davis, earmarked $6 million for the creation of an ambitious, multi-campus Institute for Labor and Employment. The ILE would build on UC's two existing industrial-relations institutes - here and at UCLA - and yield "an array of applied and policy research and outreach programs addressed to critical contemporary problems of labor, employment, and the workforce in the 21st-century California economy."

Calling the $6 million outlay "a permanent budget allocation, not a one-year expenditure," Lincoln went on to predict that the state funding "means that the Institutes will survive and, under the multi-campus structure, thrive in serving the university, the labor community, and the state for - who knows - perhaps another 55 years."

Such hopes were shared by many in California, from Democrats in the Legislature to union activists to academics with a professional interest in labor issues. Their elation, however, proved as short-lived as the government largesse that fueled it. Barely three years later, voters ousted the Democratic governor in a special election to make way for Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican whose rhetorical attacks on "special interests" extended to organized labor. And the Terminator wasted no time in taking the budget ax to UC labor studies.

Prodded by pro-business groups like the Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy - which dubbed the ILE "a union propaganda unit camouflaged by its association with the University of California" - Schwarzenegger sought from the first to trim or eliminate funding for the multi-campus endeavor. In 2004-05, when the program's share of the state treasury was already down to $3.8 million, the governor deleted what remained from his version of the budget, a move that was ultimately reversed at the insistence of legislative Democrats. The shocker came last July, when - despite what many believed was an understanding between the Legislature and the governor - Schwarzenegger wielded his line-item veto to successfully zero-out state funding for UC labor studies.

The governor's veto message blandly attributed the action to the state's fiscal woes. Previous funding, it said, "was provided on a one-time basis in the 2004 Budget Act, and these reductions are needed to help bring ongoing expenditures in line with existing resources."

But those directly affected by the cuts - including the heads of the campus's Institute of Industrial Relations (IIR) and its primary outreach program, the Center for Labor Research and Education, better known as the Labor Center - pointedly note that while the state has understandably tightened its purse strings for UC research in these lean times, only labor studies has been targeted for total elimination. That, they insist, constitutes political interference with the university's right to decide what to study and teach.

"We're a political football that gets thrown back and forth," complains Michael Reich, a longtime Berkeley professor and labor economist and the campus IIR's director for the past year and a half. "That's not good for anybody. The reality is that there's been a lot of politicking in Sacramento about our wonderful institute, which I think ought to be resolved through the academic process."

Katie Quan, a former union leader who currently chairs the Labor Center, puts it more bluntly. "In a period when there's a budget deficit and everybody's being cut back by a certain percentage, then we can understand that we've got to take our lumps like everybody else. However, if the situation is that everybody's getting cut back by a certain percentage and we're being cut back to zero on the state level, then it feels pretty much like a targeted attack," she says.

"There are pretty strong political signals being sent to us that they don't want us. I think it's very hard to make the case that there's any other agenda going on."

From Earl to Arnold

It was in the flush of America's post-World War II economic boom - and the parallel rise of its union movement - that the industrial-relations institutes at Berkeley and UCLA were born at the behest of an earlier governor, Earl Warren, in 1945. Clark Kerr, a labor economist who would go on to become Berkeley's first chancellor and president of the UC system, was the campus institute's founding director; he kept an office at its Channing Way headquarters until his death in 2003.

The labor centers followed in 1964, augmenting the existing institutes at both campuses with an outreach component. "The synergy is that they bring a lot of union people to the institute," says Reich of the dozen-plus non-faculty staff of Berkeley's Labor Center. (The institute also houses a number of smaller service units, including California Public Employee Relations and the Labor Project for Working Families.) "We learn what's going on, what their concerns are. Union people are also very interested in state policymaking, and so we find out what the hot issues are - we're not just an ivory tower."

Adds Quan, who headed the San Francisco office of the garment workers' union before joining the Labor Center in 1998, "Our main mission was to reach out to the public, to external constituents - and since we're talking about labor and employment issues, this includes workers and their unions - to be a sort of bridge between the academic world and the labor world."

That bridge seemed solid enough until, ironically, state lawmakers stepped up in 2000 to bolster UC labor studies with a $6 million infusion of taxpayer dollars. The resulting Institute for Labor and Employment, explains Lincoln, was based on Kerr's vision of a multi-campus research unit focused on labor issues and had the support of faculty and administrators on both campuses and in the UC Office of the President, including then-President Richard Atkinson.

What it lacked was financing. When Lincoln proposed that UCOP come up with $6 million for the new ILE - his estimate of what the existing labor institutes' total budget would have been if not for severe, across-the-board funding cuts for research during the 1990s - he was asked to cut the request in half. Meanwhile, prominent labor leaders - notably Art Pulaski and Tom Rankin of the California Labor Federation, the state-level arm of the AFL-CIO - persuaded union-friendly legislators to put up the full $6 million.

Beginning even before the recall election that ended Davis' governorship, however - and continuing right through Schwarzenegger's 2005 veto - the ILE was drawing fire from the Pacific Research Institute, a "free-market think tank" in San Francisco, and the Associated Builders and Contractors, a construction-industry association. The PRI twice announced that the ILE had won its "Golden Fleece" award for what the think tank called "its egregious waste of taxpayer money."

Among the activities that raised the groups' ire: a 2001 research paper on union-only agreements for construction projects; a 2002 grant award of $19,973 for a study on "Making People Pro-Union: Exploring Social Movement Dynamics in Labor Organizing"; reports on living-wage laws and the bottom-line costs of Wal-Mart workers' reliance on state safety-net programs; and a range of workshops, conferences, and other forms of leadership training they regard as the proper province of unions themselves, not of a publicly funded university.

"The ILE has a right in a free society to promulgate its anti-capitalism views," railed the PRI in a 2003 press release, "and to fund research that strikes at the heart of a basic economic freedom in America - the right of employers and employees to freely negotiate compensation. But why should taxpayers be forced to bankroll ILE's pro-union agenda?"

Quan, dismissing such attacks as "blatantly anti-labor," counters that financing for UC labor studies "pales in comparison to the amount of money that's allocated to business schools and to the agricultural extension and to lots of other entities that serve business interests."

"The university trains all sorts of professions," she continues. "It trains teachers, it trains lawyers and business people and policymakers. Why a union leader should be exempt from being trained I can't understand."

Reich agrees, calling the IIR "a really outstanding place" with "a tremendous group of scholars who are interested in labor in one way or another - with the world of work, not just unions..The world economy is changing, labor markets are changing, and we need to understand all of this more than ever."

"This should be taken out of politics," he insists. "It should be a regular part of the university. We do research, we do teaching, we do service and outreach. I think it's great that we have the resources of the university to help educate innovative leaders in the state - we do it for agriculture, we do it for business, we do it in different ways for different groups. To me it's not so controversial. We've been doing it since Clark Kerr came along in 1945."

Until the creation of the ILE in 2000, however, they were doing it chiefly under the auspices of their respective research departments at Berkeley and UCLA, not as a line item, albeit a small one, in the California state budget. Looking back, Lincoln, now an associate dean at the Haas School of Business, admits to some misgivings about the decision to go outside the UC system, a move he believes ceded too much control over the ILE to union activists. The result, he says, was a website that was "very much in your face," and a program - particularly at UCLA - that could sometimes be "an open invitation for conservative groups to attack it."

Nevertheless, Lincoln insists that Schwarzenegger "stepped in and zapped a university program for purely political reasons," and finds it "astounding" that UCOP hasn't fought back in the name of academic freedom.

"I think it's just a terrible precedent that we've allowed the governor to reach in and kill a program he didn't like," adds Lincoln. "I mean, what's next - the sociology department?"

Politics, or business as usual?

The American Association of University Professors raised similar objections after the governor threatened to blue-pencil the former ILE - which had streamlined its structure and dropped its red-flag name - in the spring of 2005. "The decision to cancel funding for these academic programs. appears to be in significant part a response to those who find the work of the scholars in these programs to be unacceptable or unpalatable, and it disregards the primary responsibility of the university's administrative and faculty officers for the curriculum of the institution," the organization wrote in a letter to Tom Campbell, then the state's finance director. (Campbell, on leave from his academic position as Haas' dean, recused himself from decisions affecting the university.)

"Consistent with respect for the autonomy of the University of California and the freedom of its scholars," the letter concluded, "we urge that funding for the university's labor and employment research programs be continued."

Four months later, after Schwarzenegger made good on his plans, nearly every Democrat in the Legislature signed on to a pair of letters to UC President Robert Dynes, noting that "$3.8 million to labor studies is a very small yet significant investment in California workers" and urging him to find the money in the UC budget.

"We will continue to work toward restoring state funding," they promised. "Regardless of the outcome of our efforts, we call upon the University of California to honor its commitment to excellence in academic research and continue funding the Labor Studies Center at $3.8 million."

For the 2006-07 fiscal year, however, UCOP proposed, and the Board of Regents approved, a total allocation of just $2.9 million - a number that Schwarzenegger, in any case, has already deleted from his version of California's budget. Reich says the regents included the funding as part of the Higher Education Compact between the state university systems and the governor, and that it should thus be safe from the budget knife. "There's nothing there about it being a separate line item," he says.

It's a cliffhanger

Dante Noto, UC's director of humanities, arts, and social-science research, has a different view. The labor money, he says, remains "a special line item," though that doesn't suggest - as some of the program's advocates charge - that OP isn't doing all it can to assure stable, long-term funding for labor studies.

"I call it 'the Perils of Pauline' - it comes in, it goes out, it comes in again," Noto says, acknowledging the impermanent nature of the program's financing and the difficulties that poses for affected staff and faculty. For the moment, though, "Our first goal is to try to work with the process as it exists.. If we completely have problems with the state, we'll look at it again."

Noto has praise for the labor institutes themselves, saying "we're very confident that the work being done is of the highest quality." But he's less sympathetic to claims of political interference in academic affairs.

"The University of California is a public institution," he observes, "and so of course there are political issues in the budget. That's one of the challenges of being a public university."

The campus institute, in the meantime, has been actively seeking to diversify its funding, charging higher fees for training and other outreach activities, staging a variety of fundraising events, and bringing in money through grants. As for whether the budget process will move in a more favorable direction, Quan is optimistic a deal can still be worked out between the governor and legislative Democrats.

Dion Aroner, who represented Berkeley in the Assembly when the ILE was created in 2000 and is now the Labor Center's "legislator-in-residence," believes even a long-term deal is possible, particularly given the interest of Assembly Speaker Fabian Nuņez, one of the ILE's champions in Sacramento.

"I think the governor can be convinced," she says. "There are so many bigger issues to deal with. You've got six million Californians who don't have health insurance. You've got hundreds of thousands of youngsters struggling with [UC] fee increases. And they're going to talk about $3.8 million?"

Reich, though, is less sanguine. "That's been discussed every year," he points out. "We seem to be a big topic of conversation in Sacramento. Everybody knows about us. Everyone told us there was a deal last year with the governor and the speaker, and the year before.

"I'm an academic," says Reich. "I'm going to wait and see what happens."