Berkeleyan

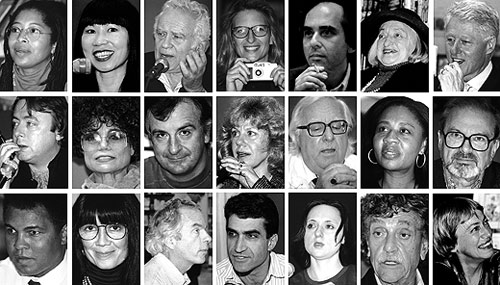

From Ali to Vonnegut, writers (and sometimes mere authors) have made Cody's on Telegraph a mandatory stop on the literary circuit. The store will soon close, to the sorrow of many Berkeleyites.(Photos courtesy Andy Ross) |

Cody's final chapter

Like a book they didn't want to end, faculty recall the glory days of the historic Telegraph Avenue bookstore

![]()

| 31 May 2006

The demise of a retail store rarely elicits an outpouring of sadness from its community, but when Andy Ross announced last month that he would be closing Cody's Books on Telegraph Avenue after years of diminishing sales, Berkeley and Bay Area book lovers responded with shock and grief.

The famously independent bookstore has been an intellectual and cultural touchstone in Berkeley for nearly five decades, hosting readings by world-renowned writers and carrying academic tomes not typically found in other bookstores.

Cody's on Telegraph "was the store I loved," said Ross in a recent interview, stopping for the first of several times to stifle tears. It's "an incredible artifact, independent of the university but part of the intellectual soup that is Berkeley," and its closing represents not just "a tragedy for my family and myself," he said, but a huge blow to the community and the campus.

A kind of postgame analysis has preoccupied many seeking to understand why Cody's flagship store is closing its doors. For his part, Ross has been surprised that local media have been quick to pin blame on the city of Berkeley and the university for neglecting Telegraph Avenue. While Telegraph "is not the shopping venue it once was," Ross acknowledges, he doesn't cite the decline of the district as the sole reason for all the store's woes and its million-dollar revenue loss over the past five years. Instead he pinpoints the dramatic change in shopping trends that has occurred thanks to the Internet. Although Cody's Books does have an online presence, it's a diminutive David to Amazon.com's Goliath.

Whatever the mix of reasons leading to the store's closing, the announcement galvanized the Berkeley City Council to approve Mayor Tom Bates's plan to clean up Telegraph Avenue beginning as early as this summer. Vacancies in 23 of the shopping district's storefronts and a 30-percent decline in sales-tax revenues prompted the plan, which will add more police, streetlights, and public-works crews to the area, increase mental-health and social services to the homeless people on the street, and simplify the city's permit process for business owners.

The improvements, if they materialize, will come too late to save Cody's on Telegraph. As testimony to its importance to the university, a number of faculty members spoke with the Berkeleyan about their memories of the bookstore that Fred Cody founded half a century ago.

A bookstore apart

Robert Tracy, professor emeritus of English, recalls that some of the problems people associate with Telegraph Avenue today were topics of discussion when the current bookstore was constructed. (The first Cody's Books was a small store on Euclid Ave., followed by a bigger venue on Telegraph where Moe's Books is now located). Tracy recalls that, in spite of the area's problems, Fred Cody was "devoted to making the Avenue work and committed himself to staying by building the new store in 1965."

Even during the '60s many businesses were leaving the Avenue, recalls Tracy. "Cody had a real belief that a bookstore was a civilizing and educational institution - and the presence of Cody's in Berkeley had a positive cultural and perhaps even moral benefit."

Ben Bagdikian, former dean of the Graduate School of Journalism, recalls that during the Free Speech Movement protests of the '60s, Cody's provided "a safe harbor for people in danger from the troops and the hostility of Gov. [Ronald] Reagan."

Bagdikian, who wrote his landmark and prescient book The New Media Monopoly back in 1983, read several times at Cody's and frequently attended other authors' readings. "The audience there was literate, very attentive, and even aggressive in its questions and knowledge," he says. Those readings were "a wonderful introduction to why Berkeley is a unique place in the U.S., if not the world."

Robin Lakoff, professor of linguistics, has read before Cody's audiences several times. She remembers a reading she gave there in 1990 from her book Talking Power: The Politics of Language, in which she took the first Bush administration to task at a time when the president's popularity ratings were high, after the first Gulf War. An audience member asked her, "Don't you think in speaking critically about Reagan and Bush that you're preaching to the converted?"

The question gave Lakoff an insight into "why it's so wonderful and dangerous to live in Berkeley. It's us against the world - which is very comforting and inaccurate. If you spend your life living in Berkeley, you're at a loss to explain when something like either one of the Bush administrations happens." With its "enthusiastic, sympathetic audiences," Cody's has been "an intellectual safe house against the encroachments of people who didn't share our particular Berkeley point of view."

Literary lights and rose petals

Cody's provided a stage for readings and author/audience interaction that was unlikely to occur in other bookstores, certainly not many of those outside the Bay Area. Professor of Asian American Studies Elaine Kim remembers trying to cram her way into the bookstore during a standing-room-only reading in the mid-'80s given by Barbara Christian, the first black woman to earn tenure at Berkeley. The capacity crowd was flowing down the stairs, she says, and kept her from getting close to the upstairs room where Christian was reading.

Poetry Flash editor Richard Silberg, who teaches courses at UC Extension, has coordinated that publication's reading series at Cody's for more than two decades. Silberg recalls when Norman O. Brown read at the bookstore in the early '90s. Brown was publicizing a re-issue of his 1966 classic, Love's Body, a work that drew on writings by Freud and Nietzsche to expand ideas of the social body and encourage people to free their inhibitions. In the middle of Brown's reading, three young women took off their clothes and (in Silberg's words) "brought out all the energies of the Berkeley unconscious. They did so "very quietly, very decorously, and were wonderfully demure in their tribute," he remembers. "It was an uninhibited, unrepressed reading."

Maxine Hong Kingston, an emeritus senior lecturer in English, recalls another tribute, one that occurred in 1966 when Ana´s Nin made a much-anticipated appearance for a publication party celebrating the first volume of her memoirs. The petite author wore a long ivory gown, and when she moved into the middle of the room to speak, Lawrence Ferlinghetti stepped behind her, raised a pail over her head, and showered her with red rose petals. "I think that was the most wonderful thing that happened at Cody's," says Kingston, who has often recalled that image. Kingston -whose books include The Woman Warrior, Tripmaster Monkey, and, most recently, The Fifth Book of Peace - says she is gratified to have read from every one of her books at Cody's.

Defying expectations at every turn

After covering post-apartheid events for The Village Voice, Adam Hochschild, a lecturer in the Graduate School of Journalism, was invited to speak at a 1994 event the bookstore held in honor of the first democratic election in South Africa, which resulted in Nelson Mandela becoming president. "What other bookstore," Hochschild asks rhetorically, "would hold a public event to celebrate a politically significant moment for a generation of people for whom the anti-apartheid movement had been very important?"

Professor of Anthropology Nancy Scheper-Hughes organized another apartheid-related event, for South African Constitutional Court Justice Albie Sachs, a humanitarian who lost an arm and eye to a car bomb, courtesy of that country's former, repressive regime. Scheper-Hughes, who describes Sachs as "a rather proper and no-nonsense white South African radical," recalls that she let the author know he might receive "some odd questions from the floor, as Cody's was a very democratic place."

After Scheper-Hughes gave Sachs a flowery introduction, the activist embarrassed her by telling the crowd, "Nancy Scheper-Hughes warned me that there might be a few oddballs in the audience, but you all look just fine." Scheper-Hughes' chagrin was short-lived: "The first question put to Albie was a left-ball from outer space. I had my revenge as Albie tried his best to respond."

Kristin Luker, a professor of sociology and law who also remembers when Fred Cody built the current store on Telegraph Avenue, holds most dear her memories of enlisting help from staffers behind Cody's information desk: "They were unlike the employees at other bookstores - they were passionate book lovers and very nice. Many times I remember one of them would look up a book for me, then say, 'I don't think this is the book you really want. I think you want this other book by so-and-so.'"

Such experiences jibe with Elaine Kim's assessment, one she has shared each fall with her students: "Cody's Books is the best bookstore west of the Mississippi," she would tell them. Even beyond the confines (spruced-up or otherwise) of Telegraph Avenue, it will likely be remembered as such for years to come.