Berkeleyan

|

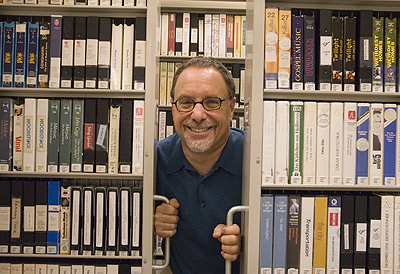

Gary Handman, director of the Media Resources Center, with some of the nearly 30,000 titles in its ever-growing collection. He buys "a lot of really bad movies," but there's method to his madness: He views movies and TV as social texts. (Deborah Stalford photo) |

Schlock today, dissertation tomorrow

Beyond Shakespeare and PBS: The Media Resources Center has built a video collection designed for a new generation of scholars

![]()

| 20 September 2006

If decades of cheesy horror flicks have taught us anything, it's never, ever to look in the basement. Evil, like mold, thrives in cellars.

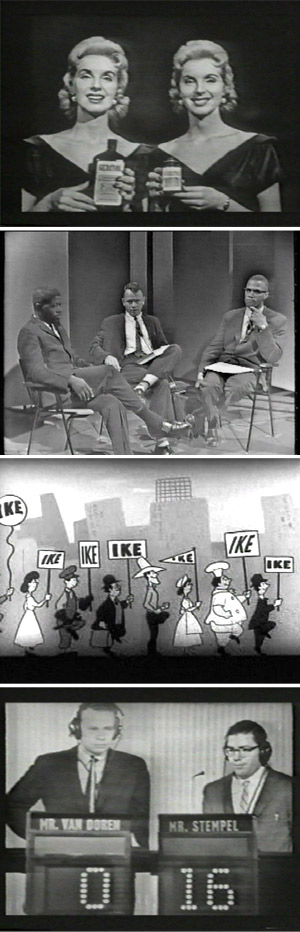

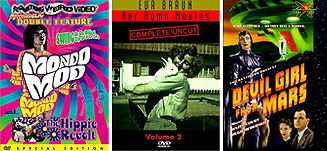

Berkeley being light years from Hollywood, though, a campus basement can be a singularly scholarly destination, the place one goes to discover the secrets that cheesy horror flicks - and their hold on the popular imagination - reveal about the zeitgeist. Should cheese lack cerebral appeal, you can also find your fill of "shockumentaries," sitcoms, cooking and quiz shows, TV commercials, archival news footage, classics of world cinema, sex-education primers, 80 years' worth of animated films, interviews with artists and activists, Soviet and Nazi propaganda, and even home movies of Adolf and Eva themselves. (And did we mention pre-TV radio programs?)

The keys to America's culture are found in visual images, and many of the most important are preserved in the Media Resources Center's collection. Above, from top to bottom: a Geritol TV spot from 1956; a 1963 interview with Malcolm X by Berkeley Professor John Leggett (center) and grad student Herman Blake; an artifact from the days of the softer political sell; and a memorable moment in quiz-show history. |

"I buy a lot of really bad movies," Handman says, not the least bit sheepishly. While the center's 6,000-strong catalog of international cinema, for example, includes many of the usual film-class suspects (Stan Brakhage, Jean Vigo, et al.), it's also chockablock with schlock from the likes of Martin and Osa Johnson, the 1930s-era husband-and-wife team known for what Handman terms "exploitation ethnographies," partially staged pseudo-documentaries shot in Africa and Asia and bearing cringe-inducing titles like Congorilla and Baboona.

In addition to "negative images of race and gender" propagated by such popular films, the MRC's director admits to a special fascination with "Hollywood's take on beatniks," as reflected in films like 1958's The Beatniks - originally titled Sideburns and Sympathy and, according to the MRC website, "commonly acknowledged as the first beatnik movie" - and 1962's Beat Girl, "the British version of Rebel Without a Cause," with stars Christopher Lee and Oliver Reed. (He also has a shelf reserved for audio rarities of such early counterculture icons as Lord Buckley.)

Personal proclivities aside, Handman believes that "film and TV can be viewed as social texts, and today's visual schlock is tomorrow's doctoral dissertation." Congorilla, for instance, shows the filmmakers teaching pygmies how to dance to American jazz - "a student of music," suggested the New York Times in its 1932 review, "might learn from this much he had long suspected." It also includes a scene in which Mrs. Johnson bravely shoots her rifle to turn back a charging rhinoceros; the footage is lifted from an earlier "documentary" in which the same animal is purportedly killed.

Some 75 years after its theatrical release, Congorilla's lessons for music students appear less abundant than the Times imagined. For anyone digging into issues of colonialism and race, however, it's a rich cultural artifact.

"I've tried to build the collection so it's useful beyond film studies," Handman explains. He's fond of a quote from media theoretician Gregory Ulmer, who wrote, "Everything wants to become television." To Handman this means that the tube "has infiltrated and reshaped our cultural and epistemological DNA, our perceptions of the world, and the ways in which we act on those perceptions. TV and the movies have, in short, given us our social, political, and ethical cues, our basic ways of interacting with the world."

Among the treasures in Moffitt's basement are Mondo Mod, Eva Braun's home movies, and Devil Girl From Mars. They may not be art, but there's plenty of data here to be mined by social scientists. |

Then, he says, "the faculty got younger," giving fresh impetus to the idea that "the moving image should be scrutinized for new reasons." Handman, with his background in film history - he currently teaches a seminar in documentary film - was ideally situated to find the best moving images to support the more linear, book-based teaching and research already being done on campus.

"It's an interesting thing about how faculty use documentaries," he observes. "They may know the print material dead to rights, but they often don't know what's out there in the way of film and video. I make sure that they know."

In contrast to many of his counterparts at other colleges, Handman takes pride in anticipating what will add value to research and lesson plans, rather than simply responding to faculty requests for movies and TV programs. "That's not the way this collection works," he says. Where others depend on a "just in time" inventory system, the MRC's approach is "just in case."

Which goes a long way toward explaining why, for anyone born after 1895 - the year the Lumière brothers' film clip of an oncoming train scared the daylights out of wide-eyed Parisians in a darkened theater - contemplating the MRC's dazzlingly varied collection is akin to being a kid in the biggest and sweetest of candy stores. Admittedly, this may not be the feeling experienced by the majority of undergrads who, at the behest of their classroom instructors, do their homework at one of 50 TV monitors equipped with VCRs, DVD players, and headphones, or in one of two group-screening rooms. But the center's collection is available to all staff, faculty, and students with a campus ID card.

Before you find a date and break out the popcorn, though, a caveat: Whatever you choose to watch, you must watch on the premises. Owing to copyright restrictions, the MRC owns just a single copy of most of its titles, and perhaps one-quarter of the collection is no longer commercially available. The average videotape has a life span of an estimated 100 viewings, and undergrads can be especially tough on DVDs. "You end up as an unwitting archivist," says Handman. The precariousness of the center's holdings, he adds, "is the thing that makes me sit up with the sweats at night."

By day, meanwhile, he's continuing to grow the collection, and is vigilant in monitoring the terrain for nonfiction films "you'll never see in theaters." (The documentary holdings stand at around 10,000 titles.) He's compiled a burgeoning archive of online holdings as well, including a wide array of campus events - talks and interviews featuring such figures as Malcolm X, Robert Oppenheimer, and Margaret Mead, or everything you've ever wanted to know about the Free Speech Movement.

The MRC website also features an extensive bibliography of reviews and supplementary materials on many titles in its collection, making the site, Handman says proudly, "more than just a catalog - it's a research tool" that draws some 4 million hits a year.

So go for the cheese, stay for the scholarship. And if you don't see what you're looking for, just ask.

The Media Resources Center can be found in the basement of Moffitt Undergraduate Library, or online at www.lib.berkeley.edu/MRC.