Berkeleyan

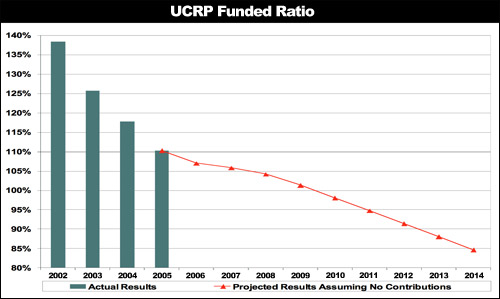

This graph shows the actual decline in UCRP's funded ratio (fund assets divided by present and future obligations) over the past several "contribution holiday" years, and projects a continued decline if no contributions are made. (UC Office of the President graphic) |

The holiday's over

Regents' plan to reinstate contributions to pension plan is a watershed event for UCRP and its members

![]()

| 18 October 2006

Our two-part report on proposed changes to the UC retirement plan begins this week with analysis and policy decisions put forward by the UC Board of Regents. In next week's issue we'll explore questions and concerns being raised at Berkeley and other UC campuses, as labor unions and UC management attempt to come to an agreement on how to fund the retirement plan in the coming years.

With many UC salaries lagging the market by a significant percentage, few matters are of such universal concern to University of California faculty and staff as the benefits package they enjoy on either side of retirement. Consequently, ongoing deliberations concerning the University of California Retirement Plan (UCRP) are being followed with intense interest systemwide, as they have been since word of potential changes first emanated from the UC Board of Regents late last year.

| UC's 'Future of UCRP' website To inform faculty and staff about the planned restart of contributions to the UC Retirement Plan, the Human Resources/Benefits office at Office of the President has established a special website accessible from its At Your Service site. Go to atyourservice.ucop.edu and select "The Future of UCRP." |

The essential news from UC is the regents' approval, over the spring and summer, of a series of actions they insist are needed to assure the stability over time of the retirement fund, which has assets of approximately $42 billion and pays out about $1.2 billion annually in benefits. Citing a projected funding shortfall in the foreseeable future unless timely and decisive action is taken, the board has stated its intention to end the UCRP "contribution holiday" in place since late 1990 - "the longest contribution holiday of any pension plan in the history of the United States," notes Randy Scott, head of UC benefits policy and program design.

Leading up to the "holiday," UCRP's assets had outstripped its liabilities for a number of years. The plan's "funded ratio" (of assets to current and future obligations, also referred to as its "funded status") reached as high as 161 percent at its peak. Since the "contribution holiday" began in 1990, UCRP's funded status has been on a decline, one that began to accelerate around 2000. Without a resumption of contributions, UC analysts project, the funded ratio will drop to 100 percent ("fully funded") around 2010, fall below 85 percent by 2014, and continue to erode in the years beyond.

To avoid a situation where UCRP would not have sufficient funds to meet its financial obligations to its retired employees, the Board of Regents set a funding target of 100 percent over the long term (any funded ratio in the "corridor" between 110 and 95 percent would be considered acceptable). The board also called for prompt resumption of contributions in July 2007. "The longer we wait to restart contributions," says UC spokesperson Paul Schwartz, "the bigger the financial deficit UC and its employees will need to fund."

How contributions to UCRP will be split between UC and its employees has not yet been set in stone. Out of 165,000-plus UC employees, about 60,000 are unionized, and any contribution from them is subject to collective bargaining with labor unions; additionally, any UC contribution is subject to state funding and the budget process.

A 'soft landing'

The regents have proposed a "soft landing" - that is, minimizing the financial impact to staff and faculty by starting contributions at a low level and ramping them up over time. The initial step would be to take the amount that employees currently contribute to a personal account called the mandatory pre-tax defined-contribution plan (about 2 percent of gross earnings for most employees, shown on monthly earnings statements as "DCP Regular" under "Retirement Savings") and redirect it into UCRP in the future.

Because this amount is already being deducted, UC emphasizes, employees would see no initial impact on take-home pay; they would also keep any funds that have accumulated in their DCP prior to the change. Figures presented at the May regents meeting - a hypothetical illustration of how a contribution ramp-up might be structured - showed the total percentage shared by UC and its employees increasing by 2 percent each year between July 2007 and July 2013, when the total contribution would reach 16 percent of covered earnings. (That 16 percent is the proportion of each plan member's covered earnings that is the estimated ongoing cost to fully fund the benefit.)

| Defined-benefit (DB) plans guarantee retirees a fixed monthly income, based on a formula (salary, age, and years of service credit are typical factors) for life, usually with annual cost-of-living increases as inflation protection. Defined-contribution (DC) retirement plans provide each employee with an individual retirement account, to which both the employer and employee contribute and which employees manage, at their own risk. |

The restart of contributions is of interest to campus units as well as to individuals. For those units with central-campus funds, monies to cover the new UCRP contribution will be included in the monthly allocation for employee benefits, says Jill Moak, senior budget coordinator in the Campus Budget Office. Units with other funding sources, including contracts and grants, will need to figure the employer UCRP contribution - probably around 2 percent, she says - into their budget plans.

Qualified faculty support

The Universitywide Academic Senate, which represents UC faculty in the "shared governance" of the university, has formally endorsed the proposed resumption of contributions to UCRP, saying it would be "irresponsible" to allow UCRP to fall significantly below 100-percent-funded status. Its blessings come with notable provisos - one being that benefit changes must not result in any deterioration in UC's competitive position when it comes to "total remuneration," the total package of salaries and benefits provided to each UC employee.

Noting that UC salaries for faculty and staff, according to consultants to the regents, lag those at comparator institutions by 10 to 15 percent, "while the value of our fringe benefits is substantially greater" than comparators', the faculty organization (through its administrative body, the Academic Council) urged that any employee contribution to UCRP "be matched by an equal or greater increase in salaries," Academic Senate Chair John Oakley reported to Senate members in a May 25 memo (www.universityofcalifornia.edu/senate/reports/ucrp.0506.pdf). "'Catch-up' pay increases" in the regents' plans "are subject to collective bargaining for some employees, and to the vagaries of the state budgetary process for all of us," he wrote. "The Academic Senate is very concerned that the 'catch-up' increases indeed materialize so the resumption of contributions to UCRP will not reduce overall remuneration of employees or damage the university's competitive position."

The council also deemed it "essential that the total (employer plus employee) contributions going into the plan be the same percentage of covered compensation for each employee. Otherwise," Oakley noted, "represented employees making reduced contributions for the same UCRP benefits would be subsidized by the higher contributions of non-represented employees, which would be unacceptable."

Citing UC financial projections, the Academic Council urged a prompt restart of contributions (in July 2007, per the regents' proposal), saying that waiting until UCRP's funded status drops to 100 percent would be "catastrophic." UC's annual payroll is $7 billion, Oakley noted in his memo to faculty. Absent a new infusion of money via contributions at the prescribed date, "Suddenly, about $1 billion per year in new money would have to be found solely to maintain UCRP's full-funded status.." he wrote.

Pension strains nationwide

Pension worries are hardly limited to the University of California. Enactment in August of a new federal law - which the Washington Post termed "the most significant changes to U.S. retirement laws in three decades" - put the spotlight on cracks in pension systems nationwide. That legislation, the Pension Protection Act of 2006, is intended to make companies adequately fund their traditional defined-benefit pensions, and at the same time encourages enrollment in defined-contribution pension plans.

The law is a source of concern for some observers, particularly those who favor the maintenance of defined-benefit plans (such as UCRP) against the rising tide of defined-contribution plans; the latter put an increased burden on workers to manage their equity-based accounts (in the form of 401(k) plans, for example, or 403(b) plans in education and certain nonprofits), but appeal to employers because of the cost savings they offer.

Pension debacles at Enron, Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, and WorldCom, as well as at hundreds of smaller companies, are reminders of the less dramatic but steady erosion of retirement security benefits nationwide. When United terminated its pension plan, for example, it was underfunded by two-thirds (that is, the $15 billion defined-benefit plan had only $5 billion in assets at the time). To make those employees whole required shifting the burden of funding to U.S. taxpayers, through the federal Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. (PBGC).

The health of city and state pension systems, increasingly, is under the spotlight as well - from San Diego (where city leaders are facing a cascade of legal and political problems as fallout from a pension-fund scandal) to New York City (where, according to a recent New York Times series, city workers' pension account is either "fully funded," by one of its managers' accounting methods, or underfunded by $49 billion by an alternative calculation buried in its financial reports). Nationwide, the Times reported, "state and local governments owe their current and future retirees roughly $375 billion more than they have committed to their pension funds" by one estimate; that number balloons to $800 billion, it wrote, "if America's state pension plans were required to use the same methods as corporations." Public-employee pension funds are not covered by federal pension law, held to a uniform accounting standard, or protected by the PBGC; instead they're governed by boards with relatively little oversight, and must appeal to the taxpayers to fill the gap if they end up in the red.

News reports in this vein dispose many UC employees to welcome the regents' plan for keeping UCRP solvent. Michael Glogowsky worked for a number of large corporations prior to accepting his campus post as director of financial planning and budget for the vice chancellor for administration. He calls UC's defined-benefit plan "extremely generous" compared to the defined-contribution plans offered by his former employers in the private sector.

Given what's happening in that sector - Glogowsky cites Delta Air Lines, which recently won a bid in bankruptcy court to terminate its pilots' defined-benefit pension plan, underfunded by some $10 billion - the options are "pretty simple" in his view: "If you don't properly fund the pension benefit, you put future recipients at risk. I support whatever contributions are appropriate to keep UCRP sound."

In the second part of this special report, appearing next week, we'll look at employee reactions to, and concerns about, the pending renewal of employee contributions to UCRP, and share insights and advice from faculty with expertise in pension funding and regents-watching.