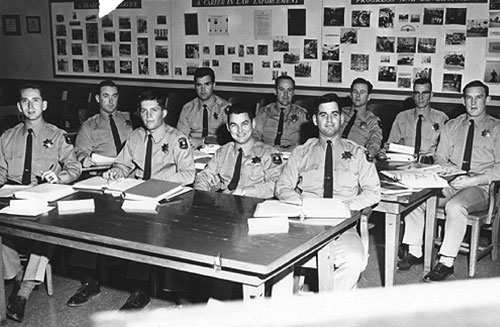

The demographics of the City of Berkeley Police Department — like those of many other U.S. cities — have changed considerably since the mid-1960s, when this group of police recruits went through training. Today the force of 184 sworn officers includes 37 female officers (17 of them of color) and 147 male officers (65 of them of color). Women and minorities remain concentrated in the lower, patrol-officer ranks, though the force currently has three African American captains, one of whom is a woman. (Photo courtesy David Sklansky) |

Berkeleyan

Boalt Hall prof explores changing demographics of police

'Bottom up' workplace innovations, says David Sklansky, might spur democratic reforms

| 16 November 2006

Police departments are not typically known as wellsprings of social foment — which made a conference at Berkeley last month on "Police Reform From the Bottom Up" all the more remarkable. Scholars and police leaders from four continents converged to discuss a range of underexplored topics: police unions and police officers as change agents in police reform, the role of black officers in modernizing policing, leadership-sharing in police agencies, and the possibility that workplace democracy could help transform policing.

Co-organizing this unlikely meeting of minds was David Sklansky, a Boalt Hall professor whose interest in the convergence of policing and democracy straddles a traditional divide between social science and legal studies.

"Lots of law professors write on the legal regulation of the police," he says, "and their work exists alongside studies of police by sociologists, political scientists, and anthropologists….What I'm doing now draws heavily on both and, I hope, speaks to both."

David Sklansky (Peg Skorpinski photo) |

Sklansky's academic home is solidly in the legal-scholarship camp. An expert in criminal law, procedure, and evidence, he joined the Boalt faculty in 2005 after a seven-year stint as assistant U.S. attorney in Los Angeles and a decade as a UCLA law professor. Yet his study of U.S. criminal law — whose evolution in recent decades, he says, has been deeply influenced by "the intuition that the police need to be restrained in order to make their activities consistent with a democratic society" — drew Sklansky into the gravitational field of the social sciences.

"Police can threaten democracy in various ways," he notes. "They can squelch dissent; they can make it difficult for political activity to flourish; they can frustrate efforts to have the government treat all its citizens with equal dignity and respect." Conversely, he adds, "some democratic aspirations depend on policing." Police are a necessary instrument, for instance, "in shielding vulnerable parts of the population against more powerful parts" — be they women subjected to domestic violence or minorities terrorized by hate crimes. In minority communities, for example, "the longstanding complaint has been not just of harassment and violence at the hand of police, but also the failure of the police to provide minimally adequate protection against crime."

Policeman as other

To study more rigorously the ways that policing can enhance or stifle democracy — and that democratic practices and structures can help reform policing — "I had to learn a lot about democratic theory," says Sklansky, "but also to immerse myself in the rich body of work that sociologists, political scientists, and anthropologists have done about the police."

A central tenet of "police studies," beginning in the 1950s, is what Sklansky calls the "police-subculture schema" — a view of police, supported by a litany of scholarly studies, "as a discrete and unified group, alienated from mainstream society and inherently hostile to democratic values," he writes in a forthcoming journal article, "Seeing Blue." Police officers' shared alienation has led to distinctive group norms — such as the selective use of illegal violence against suspects and a code of silence regarding fellow officers' illegal activities — that fly in the face of law enforcement's legal mandate.

Sklansky says that for more than half a century the police-subculture schema, periodically reinforced in the public mind by high-profile incidents of police misconduct, has influenced evolving standards of criminal procedure as well as citizen efforts at police reform. Civilian review boards, aimed at reining in the police, and community-policing initiatives have been the major focus of police reform across the country. Meanwhile, he believes, other avenues of reform have gotten short shrift — "notably those … that focus on institutional design rather than occupational culture, differences between officers rather than similarities among them, and rank-and-file participation rather than top-down control."

Demographic sea change

In "Not Your Father's Police Department," an article published this spring in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Sklansky summarizes and discusses "differences between officers" resulting from the new demographics of law enforcement. The past three decades have seen a dramatic shift in police departments as a significant number of minority, female, and (in some cities) openly lesbian and gay officers have joined formerly straight, white, male police enclaves. (In 1970, for instance, African Americans made up about 6 percent of sworn officers in the country's 300 largest police forces, compared with 18 percent today. In 2004, the International Association of Chiefs of Police included, for the first time, a workshop on LGBT officers at its annual meeting.)

Although some observers insist that these demographic changes are merely cosmetic, Sklansky thinks the changes go far deeper. The jury is still out, he admits, on to what extent a more diverse police force translates directly to better working relationships and greater credibility with minority communities.

For instance, he writes, there are studies "finding that black officers shoot just as often as white officers; black officers arrest just as often as white officers; … black officers get less cooperation than white officers from black citizens…." Other studies, however, contradict such findings, he notes. Research on female officers' performance is similarly inconclusive.

Organizational effects of police diversity are discussed less often, but it's in the arena of internal department dynamics where the clearest benefits are found, Sklansky believes. The demographic sea change in law enforcement — though incomplete and possibly slowing — appears to have brought increased division, distrust, and resentment within police forces. "The decline in solidarity is everywhere apparent," Sklansky writes. "In between calls to service, police officers are a less cohesive group than they used to be." But that appears to be a very good thing, he hastens to add: "Police effectiveness does not appear to have suffered, a range of police pathologies have been ameliorated, and police reform has grown easier and less perilous."

Sklansky is particularly interested in the recent inclusion of openly gay and lesbian police officers and in how that trend may affect "the hyper-masculinized ethos of the profession, and the tacit acceptance of extra-legal violence." After World War II, through the McCarthy period and into the 1960s, he notes, "police were involved in a particularly horrific period" of entrapment and extra-legal violence against homosexuals — "believing probably correctly" that society expected them to deal with these citizens "largely off the books."

Sociologist William Westley (who helped launch the field of police studies through his pioneering ethnography of a Midwest police department in the 1950s) argued that the policing of homosexuality (and of sexual conduct more broadly) in that era fostered a tolerance of illegal violence among police.

"Westley was not the last sociologist to suggest that homophobia has been an important force in shaping police culture," Sklansky says. A related question — which he's researching for an upcoming symposium marking the 40th anniversary of Katz v. U.S., a watershed 1967 Supreme Court ruling on privacy and electronic eavesdropping — is how the policing of homosexuals has affected the evolution of criminal-procedure jurisprudence itself.

Papers from "Police Reform From the Bottom Up" are online at law.berkeley.edu/faculty/sklansky/conference/.