Berkeleyan

|

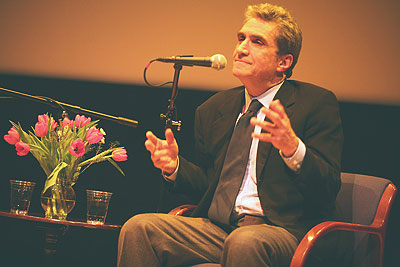

Poetry "emphasizes each individual's voice," said Robert Pinsky at a campus appearance last week. That's an aspect of the art he finds valuable in a culture where celebrities are treated like royalty. It is not, he added, "a minor branch of show business" but "an inherited and inexhaustible mystery."(Mimi Chakarova photo) |

Poetry's 'inherited and inexhaustible mystery'

Robert Pinsky's Favorite Poem Project celebrates the human scale of verse

![]()

| 08 February 2007

By the end of last Thursday night's "Forum on the Humanities and the Public World" in Wheeler Hall, Robert Pinsky had made a persuasive case for the necessity of verse in American life.

"Poetry is very important," said the former U.S. poet laureate, "but so is flying a very big airplane full of people or trying to cure illnesses or cope with man-caused global warming."

Pinsky, who taught in Berkeley's English department in the 1980s, spoke at the inaugural forum of the Townsend Center series. "The lyric is not the single greatest public medium, but poetry is central and fundamental," he observed. Poetry is "a marker for literacy, the way certain plants or birds are markers for vitality and health in an ecosystem," he said, crediting another former U.S. poet laureate, Berkeley English professor Robert Hass (who was in attendance), with that description.

Pinsky himself took the measure of the poetic ecosystem when, as poet laureate, he initiated the Favorite Poem Project in 1997. With support from the Clinton administration and the National Endowment for the Arts, Pinsky fashioned a portrait of the United States through the year 2000 as seen through the lens of poetry.

The project's organizers put out a call for submissions, asking Americans to explain the personal significance of a poem of their choosing. The 18,000 people who responded to the request during its one-year window ranged in age from 5 to 97, hailed from every state, came from diverse backgrounds and occupations, and had varied levels of education. Pinsky assigned graduate-student assistants the task of sorting through the submissions, instructing them to look for interesting relationships between the respondent and his or her selection.

The results have been collected in three anthologies (all published by W.W. Norton): Americans' Favorite Poems (1999), Poems to Read (2002), and An Invitation to Poetry (2004). Each volume offers a diverse sampling of poets - Sappho, Andrew Marvell, Shakespeare, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Gwendolyn Brooks, Rabindraneth Tagore, and a host of contemporary poets. The 2004 collection includes a DVD of 27 short documentaries in which readers talk about their connection to their chosen poem, and then read the work. (PBS's NewsHour With Jim Lehrer broadcast many of these shorts.)

Before screening a trio of segments from the Favorite Poem Project DVD, Pinsky described "a plausible but fake and very widely accepted crisis" in American poetry that amounts to "baloney." That faux crisis might be summed up as "'Oh, poor American poetry. It's gotten too fancy and highbrow and weird, and you have to sell it like soap.'"

Pinsky ridiculed the notion that in this era of digitized culture, "poetry is going to die unless it becomes less elitist." Poetry's critics charge that "it should be less gloomy, more genial, less jagged and modern, more charming, something you can hum along with or chuckle at," he said. Nostalgia for the "good old days when poetry was sung or chanted to people who were happily chewing slices of venison and drinking mead or sarsaparilla" is nothing new, said Pinsky. Ezra Pound, who railed against this idea back in the first half of the 20th century, entitled his rant "The Constant Preaching to the Mob."

Poetry for the people

Lyric poetry is "intimate in scale" and illuminates other areas of American life - things we do every day, things we worry about, politics, making money, health," said Pinsky.

Videos made for the Favorite Poem Project demonstrate "this ancient art depends not on a mass medium but on a medium that by its nature is on a human scale," explained Pinsky. Neither words nor images - not even the performance of the reader - function as the conduit for a poem. Rather, "the medium - literally, the thing that comes in-between - is the reader's actual or imagined voice. It is the breath of whoever reads the poem - either your actual breath saying the words or that of your body where it starts to feel the meaning stirring in it."

Starting with Seph Rodney, a Jamaican immigrant who came upon Sylvia Plath's "Nick and the Candlestick" after a disappointing date left him feeling bereft, the segments Pinsky screened eloquently demonstrated his point about the physicality of poetry.

Rodney, who once considered poetry "grandiose" and "highfalutin'" was surprised by how "powerful, rough, bitter, and caustic" he found Plath's poem, while it also communicated to him "a real urgency about the need for love."

Another segment featured John Doherty, a Massachusetts construction worker, who read an excerpt from Whitman's "Song of Myself." Doherty had once dismissed poetry as "wrong words, wrong order." Pinsky embraces such criticism: "I like writing for an audience that includes people with no automatic reverence for poetry. It suits me that there is an audience to listen, but they're not automatically convinced. They're not pious about it."