Berkeleyan

What's the frequency, Bill?

Journalism-school professor William Drummond tunes in to satellite radio, and likes what he hears

![]()

| 28 February 2007

If last week's proposed merger between satellite-radio operators XM and Sirius wins approval from the Federal Communications Commission, Wall Street investors won't be the only ones celebrating. Prospective subscribers will no longer have to ponder the question: XM or Sirius?

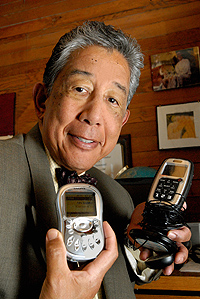

Journalism professor Bill Drummond, seen here with handheld hardware capable of pulling in signals from satellite radio, says he found listening to the new medium "so entertaining and so much fun that I never turned back to terrestrial radio."(Peg Skorpinski photo) |

William Drummond, a professor at the Graduate School of Journalism and a pioneer in the development of news and information in public radio, wasn't surprised by the satellite providers' announcement - "I didn't think there was room for two players," he says - and predicts that if the merged company combines the best of both services, a stronger product will result.

One of the strengths of the medium is that the communications satellite that broadcasts satellite radio's digital-radio signals covers a much wider geographical range than any traditional terrestrial radio station can - a boon for its many long-distance trucker subscribers and others who travel out of range of favorite local stations. Another selling point is that the number of channels satellite radio can offer is "limited only by the imagination and the number of deals providers can cut," explains Drummond.

The broadcast schedules of XM Satellite Radio and Sirius Radio include a vast range of choices in music, talk, in-depth news, and sports coverage. Each operator has also attempted to best the other with its celebrity programming. Bob Dylan, Oprah Winfrey, Snoop Dogg, former NPR Morning Edition host Bob Edwards, Ellen DeGeneres, Tom Petty, and Wynton Marsalis all helm programs on XM. Sirius Radio counts shockjock Howard Stern, 50 Cent, Martha Stewart, "Little Steven" Van Zandt, Eminem, Nascar Cup series champion Tony Stewart, and Mojo Nixon among its marquee talent. Plus - and this is no small consideration - even with all that star wattage, satellite radio is commercial-free. At the close of 2006, Sirius subscribers numbered 6 million, while XM ended the year with 7.6 million subscribers.

From radio's golden age to its resurgence

To put the new medium into context, Drummond, who's been teaching courses in radio journalism at the J-School for 20 years, this semester is offering Satellite Radio: Breaking the Bonds of Earth as a freshman seminar. The class provides students with a broad overview of radio - from the medium's golden age to its slow fade in relevance during the birth and widespread adoption of television to its resurgence in 2001, one that the veteran journalist says coincided with the launch of satellite radio. "I want the students to understand how radio shaped and reflected the politics and culture of its time," says Drummond, who calls radio "the first electronic mass medium."

Drummond himself jumped on the satellite-radio bandwagon relatively early: He had a Sirius unit installed in his car in 2003, and now listens to XM on a portable satellite-radio player. Initially, though, the founding editor of National Public Radio's Morning Edition was, by his own admission "a big skeptic. If you check, you'll see me quoted in new stories saying, 'This will never fly.'" Having assumed at first that consumers wouldn't pay to have more choices, he now admits, "The fallacy in my thinking was in thinking that satellite radio offered the same product as terrestrial radio."

By the time Drummond decided to investigate satellite radio as a consumer, he had concluded that terrestrial radio "had long been not very interesting," in large measure because of increasing consolidation in the broadcast industry. A shift in radio had started in the early 1990s, when many stations were struggling financially. In 1996 the powerful broadcast lobby swayed Congress to lift the limit on the number of radio stations a company could own. Media conglomerates such as Clear Channel began scooping up stations, a move that had serious repercussions for the music industry.

"The Clear Channel approach is to play music that's going to bring in the widest possible listenership," says Drummond. Clear Channel stations generally draw from a limited playlist in which the Billboard hits of the day are in heavy rotation. As a result, only a narrow range of music gets on the air. By contrast, satellite radio offers 60-odd genres with potentially huge playlists, says Drummond, who quickly went from being to a doubter to an evangelist.

His own listening habits and even tastes have changed since subscribing to satellite radio. After delving into old radio programs from his youth, Drummond began exploring new musical horizons and developed an interest in opera. Mostly, he samples widely from satellite radio's smorgasbord: "I rarely stay with any channel longer than two weeks, whether it's talk or music, because there's so much out there and it's changing all the time."

Old-time radio, opera, and Larry the Cable Guy

Unlike cable TV, which Drummond says offers very little quality in spite of its numerous channels, "Satellite radio is an entertainment venue that does not waste your time. If I get bored listening to music, all of the different talk programs are over the top." (He delights in the irreverence and risqué humor of Jeff Foxworthy and Larry the Cable Guy on Sirius Radio's "Blue-Collar Comedy" channel.) "Sometimes I'll just spend my driving time listening to right-wing talk radio just to see how weird those guys are," he says. While the commentators on the right "actually have a program pitched to gun owners and NRA people," he observes, the left-wingers who host satellite-radio programs "tend to mock their counterparts on the right and the Bush administration, and take their cues from Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart."

It's too early in the semester for Drummond to predict whether the eight students in the seminar will be swept up in his enthusiasm for the medium. He's uncertain whether college students will shell out money for satellite-radio hardware in addition to a $12.95 monthly subscription fee. After all, he observes, "This whole generation has grown up in an era when they believe, 'If I pay for an iPod, I should get everything that goes in it for free.'"

Still, he's willing to prognosticate about terrestrial radio's future - one he thinks is not particularly bright: "It's in for some really tough times. Look at Clear Channel. They bought up all of these radio stations, and now they're finding they can't make money from them, so they're trying to get rid of them."

Clear Channel and its sibling conglomerates took a critical misstep, says Drummond, when they decimated their radio stations' news infrastructure. That move cost them listeners after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when people hungered to understand what was going on in the world. "The best of the demographics, the people with disposable incomes who drive Volvos, went to public radio and never came back," he says.

If the XM-Sirius merger gets approved, he predicts, "the value of terrestrial radio will almost approach zero."

Drummond is more optimistic about the future of satellite radio. "The cost is pretty cheap relative to other diversions," such as the Internet and cable TV, he says. "The reason I think satellite radio is going to stabilize and be strong is that the one thing we haven't figured out is how to get people from point A to point B. Commuting doesn't get faster over time, and because people are going to spend more time confined in their cars and need to watch the road, they're going to spend time listening. Satellite radio is a huge, huge answer to that problem."