Berkeleyan

Stories in the Time of Cholera wins top book prize for anthropologist and public-health researcher

![]()

| 04 April 2007

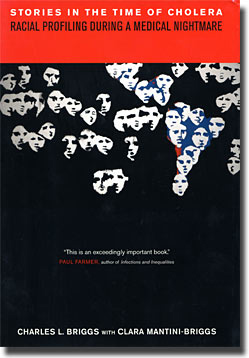

Charles Briggs, a professor of anthropology, and Clara Mantini-Briggs, an associate researcher in the demography department, are the 2007 winners of the J.I. Staley Prize, one of the most prestigious prizes in the field of anthropology, for Stories in the Time of Cholera: Racial Profiling During a Medical Nightmare, a book they co-authored.

|

The honor, which carries a $10,000 award, marks the fifth time since the award's inception in 1988 that a member of the Berkeley faculty has won the prize from the School of American Research for an outstanding book in anthropology - more times than scholars from any other university.

The book recounts the 1992-93 cholera outbreak that killed some 500 people, mostly indigenous, in eastern Venezuela's Orinoco River Delta. The disease had been absent from Latin America for nearly a century. Cholera can kill healthy adults in as little as 12 hours and can make a 15-year-old appear geriatric, Briggs and Mantini-Briggs note in the book, but is prevented easily by the provision of uncontaminated food and water and is easily treated.

Briggs and Mantini-Briggs, who are married, plan to use the prize money, along with royalties from the book, to launch a project to assist rainforest residents in their efforts to improve their health conditions.

Published by UC Press in 2003, the book traces across a global panorama the role in the disaster of inadequate medical services, social inequality, public-health practices and racism.

At a time when new and re-emerging infectious diseases threaten populations around the globe, the cholera outbreak in Venezuela and the regional, national, and transnational forces that contributed to it offer important lessons, write Briggs and Mantini-Briggs.

The book draws from hundreds of interviews conducted from 1992-99 with people from a cross section of ages, occupations, social positions, and degrees of bilingualism in the delta region, and the Venezuelan capital of Caracas. The authors recorded the stories of medical personnel, journalists, families of those killed by cholera, disease survivors, community leaders and government officials, traditional healers, missionaries, and others.

They also spoke with authorities at agencies such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, the Pan American Health Organization in Washington, D.C., the World Health Organization in Geneva, and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh about cholera research and how related policy is established.

Some stories, the authors note, attributed the Venezuelan cholera outbreak to geography and the indigenous culture, essentially blaming the victims of the disease. Many delta residents, the authors write, thought in broader terms, seeking to explore the unintentional results of globalization, economic and political crises, global trade, and racial inequalities, while others characterized the outbreak as an opportunity welcomed by some to exterminate indigenous people. Rather than joining the blame game, Briggs and Mantini-Briggs say they instead explore why dedicated, well-trained professionals were unable to prevent the medical nightmare.

"The problem is that stories are just as real as germs and bottles of rehydration solution," the authors write.

For example, they say that media reports could have made public-health officials more accountable, but when these officials were constantly quoted by the press, they were seen as the sole authoritative information sources about the outbreak, and this tended to mute the stories of people living in the affected communities.

Paul Farmer, a professor of social medicine at Harvard University and the 2006 Staley Prize winner for his book Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights and the New War on the Poor, says in a review of Stories in the Time of Cholera that the book should appeal widely to people in the fields of social science and public health, but also should be required reading for the media and public authorities "whose prejudices clearly compounded the injuries meted out by the microbe itself."

Other Berkeley anthropologists who have won the Staley Prize include Terrence Deacon (2005, The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain), Lawrence Cohen (2003, No Aging in India: Alzheimer's, the Bad Family and Other Modern Things), Nancy Scheper-Hughes (2000, Death Without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil), and Patrick Kirch (1998, co-author of Anahulu: The Anthropology of History in the Kingdom of Hawaii).

Briggs and Mantini-Briggs will officially receive the prize in November at the American Anthropological Association meeting in Washington, D.C. Their book also won the 2004 Bryce Wood Book Award from the Latin American Studies Association. In November 2006, Briggs won both the Edward Sapir Book Prize, the highest award in linguistic anthropology, for co-authoring Voices of Modernity: Language Ideologies and the Politics of Inequality, and the Rudolf Virchow Award from the Society for Medical Anthropology.