Berkeleyan

|

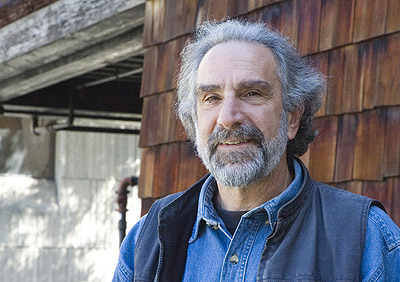

Stan Kramer is retiring after 35 years in campus show biz. (Wendy Edelstein photo) |

A life in theater, sans histrionics

Whether crafting faux shrubbery from scratch or building a bridge held up by nothing, TDPS's Stan Kramer has always 'given the play its due'

![]()

| 26 September 2007

For more than 35 years, Stan Kramer has worked entirely behind the scenes on campus theater and dance productions. So it's no coincidence that when he retires next week as technical director for the Department of Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies (TDPS), he will do so without much fanfare or hoopla.

Even lovers of live performance may be hard-pressed to define a technical director's responsibilities, which can vary among theater companies. For Kramer, that title has embraced duties ranging from building and eventually breaking down scenery for hundreds of productions to training student actors and crew members in how to use what he constructs.

| The Department of Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies employs 18 permanent faculty/lecturers and nine guest lecturers. The department annually produces four to six main-stage productions (directed and designed by Berkeley faculty and guest artists with student actors, dancers, crew, and technicians) and seven to 10 workshop productions that are directed, designed, and performed by students. For information, visit theater.berkeley.edu. |

Kramer's work begins once a director and set designers decide on the look, theme, or emphasis of their upcoming production. "Do they want to do a modern-dress version of Hamlet or a traditional Shakespearean version in doublets and tights?" Kramer offers as an example of the direction he needs. Once such decisions are made, the designer generates a set of drawings from which the technical director begins to budget his part of the production.

"My job is to figure out how to build the show" and do the different tricks the director and designer request, he says. Though the self-effacing Kramer describes his role in very plain terms, Peter Glazer, associate professor in TDPS, puts a glossier spin on his contributions: "He sees the big picture and attends to the smallest details, with care and consideration, giving the play its due, and then some."

After pricing materials, Kramer and the designer discuss whether the show will be built from steel or wood, plastic or fabric. "There's a lot of engineering involved in figuring out whether something's going to be strong enough," notes Kramer, who typically has six to eight weeks to build the scenery. "Sometimes a designer will want to span a huge expanse with a platform that people will walk on and do things on with no visible means of support."

Kramer's matter-of-fact description again downplays his key role. Marni Wood, professor of dance for 35 years and chair of the department for several years in the 1980s, praises his talent for "creating an atmosphere in which art can really happen. He understood how to collaborate, go from concept to actuality, and fit his creative side into the practical side of production seamlessly."

Unlike his counterparts outside academia, Kramer's charge goes beyond constructing scenery. The TDPS scene shop is used as a lab for several of the department's courses, "and all of us who work there are instructors," he says. Students enrolled in Theater 60, Introduction to Stagecraft, are required to fulfill a set number of hours in the scene or costume shop or work on the crew of a current production.

Kramer says that when he taught the stagecraft class he "tried to instill in students a sense of the complexity of putting on a show" by emphasizing how many design departments within TDPS contribute to each production. He and his staff keep students involved in the process when they're ready to build the scenery: "We try to train them to do everything - to use all of the equipment, and to learn as much of the process as we are using for that particular show as they can."

Students learn that behind-the-scenes work is far from glamorous. In last year's production of Suburban Motel, student assistance was critical to the construction of an element of the set - a big hedge. "It's very simple to do the armature or the underlying construction" on such a thing, explains Kramer. "You cut some pieces of plywood in a particular shape and cover it with chicken wire. But it's very time-consuming to fill the chicken wire with tiny pieces of crepe paper." Hence: student labor.

But Kramer takes care to let students building scenery know "they're an important part of the production. Without what they're doing, the show would be different. It may work in a different way - or it may not work - but the show would definitely be different without their contribution."

A cautionary mentor

Still, when students considering a behind-the-scenes career ask for advice, Kramer tells them, "Don't go into show business; go get a real job." His cautionary tone is only half-serious, and he's pleased that many of his students have gone on to be successful in the technical aspects of theater or TV. One former student is the lighting director for The Ellen DeGeneres Show. Others are running the scene shop or the stage at A.C.T., working as union stagehands in San Francisco, or employed at George Lucas' Industrial Light and Magic.

Kramer's own theater career was far from designed. Although he worked in a scene shop as an undergraduate at Brandeis, in 1971 he came to California with no real plan. A friend from college was employed as the electrician for the precursor to Cal Performances. "I had just come by to say 'hi,' and he put me on the payroll of the Committee for Arts and Lectures," Kramer recalls.

In 1975, Kramer moved to the theater department (then called the Department of Dramatic Art) for a job as second carpenter. Four years later he became master carpenter, assuming the technical-director position in 1983.

To keep himself challenged, he took up designing shows in the early '90s. "The most satisfying shows to design were the ones where I wasn't just providing a visual element to someone's conception, but developing something that actually made a big difference to what the show was ultimately about, a true collaborative endeavor," he says. Kramer's design credits include The Lorax (1994), Death and the Maiden (1996), The Caucasian Chalk Circle (2000), John Fisher's Cleopatra: The Musical (2000), and The Cradle Will Rock (2005).

Yet Kramer isn't keen to revisit past successes: "There's a saying we have in the theater," he explains. "'You're only as good as your last show.' I try not to get puffed up about things."