Berkeleyan

|

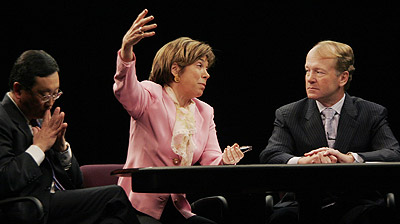

Haas professor Laura Tyson animatedly makes a point to John Chambers, Cisco's CEO, during a panel discussion at last week's TechNet Innovation Summit. Pondering at left is John Chen, who heads Sybase. (Photo courtesy TechNet) |

At Zellerbach, visions of the technological

Charlie Rose, Laura Tyson, and some of Silicon Valley's best and brightest chart a high-tech path to increased competitiveness and greener energy

![]()

| 17 October 2007

Arnold Schwarzenegger, a hoped-for participant, never appeared for his close-up, but an audience of technophiles at Zellerbach Hall last Thursday (Oct. 11) did get to see and hear such luminaries as TV's Charlie Rose, a half-dozen Silicon Valley machers, and Berkeley's own Laura Tyson make the case for technology as the way to increased economic competitiveness and reduced global warming.

Thomas Friedman, the New York Times columnist, was not on the bill for the TechNet Innovation Summit, organized by the bipartisan advocacy group of high-tech executives and sponsored by the campus Government and Community Affairs office. But he was unmistakably present in spirit, invoked frequently by name and via references to his bestselling book on globalization, The World Is Flat.

There seemed little argument Thursday, during back-to-back hourlong discussions on innovation and green energy, that the world is not only flat - that is, the global economic playing field no longer tilts significantly toward the biggest and richest countries - but is getting flatter all the time.

"I think borders and boundaries will come down," predicted Cisco CEO John Chambers, part of a panel that included Sybase's John Chen and Tyson, a professor (and former dean) at the Haas School of Business and chair of the President's Council of Economic Advisers under Bill Clinton. "It's inevitable that the world will be flat, the jobs will go to where the best infrastructure is, [where there is an] educated workforce, the environments that create innovation, and supportive government. They go, all four, together. And that's a trend no one can stop."

Government, however, "is not flattening enough," insisted Tyson. "I personally believe there's no way around the reality of much more multilateral, or cooperative, global government. It has to be."

All three panelists seemed to agree that while the United States still has the competitive advantage when it comes to technological innovation, the rest of the world - particularly China and India - is narrowing the gap.

"They're more hungry than we are," said Chen. "I think they're doing a lot of the things that we used to do."

Moreover, Tyson pointed to the so-called "compression of development time," which allows America's competitors to reach the technological frontier far more rapidly than ever before. "Right now, if you look at the U.S. workforce, we have the most educated, experienced workforce in the world," she said. But partly due to the lack of emphasis here on math and science in K-12 education, she added, "you would have to say that the competition is catching up."

"I think of innovation - having spent most of my life in academic institutions - as very much in the minds of the people, the creators," Tyson said. "And so it is very, very important in thinking about innovation policy to think about such things as high-school dropout rates, percentage of students who are getting B.A.s in math and science disciplines, where our Ph.D.s in the United States are coming from.

"If you look at those kinds of indicators," she concluded, "you see that one of the threats to innovation in the United States is that we're not building our people-power adequately, starting with high-school completion rates, starting with K-12 math training, all the way through Ph.D. education."

She and her fellow panelists also agreed that current U.S. immigration policies are putting the U.S. at a competitive disadvantage.

Chen, a Caltech graduate who was born in Hong Kong, complained that half the Ph.D.s in the U.S. are from foreign countries, having come here for "the best postgraduate higher educations in the world." Yet as soon as they earn their degrees, he said, "we want them to leave."

"Our immigration policy today," said Chen, "makes absolutely no sense."

A second group of panelists, organized around the topic of "green innovation," also took a few swipes at America's political leaders. John Doerr, a venture capitalist with Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, was asked by Rose to explain the lack of leadership on moving to counteract global warming by developing less-polluting energy sources. Doerr referred him back to the 2000 presidential election: "It's because of 800 votes in Florida."

Rose also noted that Doerr had traveled to Brazil with "my good friend and yours," columnist Tom Friedman, prompting several more laughter-inducing shots at American politics. Brazil, noted Doerr, has become "almost oil-independent" via a program to make ethanol from sugar, and now powers most of its passenger vehicles with homegrown ethanol. Yet Brazilian ethanol can't be imported into the U.S., he said, without paying a 54-cent-per-gallon tariff - a tax, he added, that "might have something to do with the fact that presidential primaries are held in Iowa."

While in Brazil, Doerr said, Friedman asked "the father of the Brazilian ethanol revolution," Josť Goldenberg, about the U.S. tariff. "Is this stupid," inquired Friedman, "or really stupid?" (Goldenberg's reply was not reported.)

Larry Brilliant, executive director of Google's philanthropic arm, Google.org, pointed out that rising demand for corn-based ethanol has resulted in higher corn prices and food shortages, and termed the increases "an extremely regressive tax on food."

Doerr, acknowledging problems with corn-based ethanol, said it nevertheless "primes the pump" for alternative fuels, and "gets the transition going."

John Melo, chief executive of Amyris Biotechnologies - the firm co-founded by Berkeley scientist Jay Keasling to produce an inexpensive synthetic version of the anti-malarial drug artemisinin - offered some insight into how that transition might work.

"We learned that we could engineer microbes not just to design artemisinin, but we could design them to make fuels - not just any fuels, but fuels that are renewables, fuels that are hydrocarbons," explained Melo, who spent nearly a decade in the oil industry. "Alcohol is very good - especially if you want to get drunk. It's not quite as good for powering vehicles."

"Our focus was, could we develop a product that was identical to gasoline, that was identical to diesel, that was identical to jet fuel," Melo continued. "And we've successfully done that. We've actually designed a bug to produce hydrocarbons that are products that in many ways are better than the fossil fuels we have today. And that really is what we compare ourselves against."

Led by Keasling, the effort to develop biofuels through synthetic processes is among the promising avenues of research to be conducted under the rubric of the Energy Biosciences Institute, the $500 million project based on the Berkeley campus and funded by oil giant BP.

It was Doerr, however, who best articulated the hope inherent in such research. "A dear friend of mine, Richard Newton, was the head of engineering here at Berkeley," he said, noting that Newton died last year of cancer. "Before he passed away, he grabbed me by the collar and said, 'John, more important than the Internet, the most important technology of the future is synthetic biology.'"

Jonathan Schwartz, president and CEO of Sun Microsystems, made the point - as did others, in different ways - that the next "green revolution" will come about only when economic incentives align with societal needs. "We talk about the green revolution as if it's a social revolution and not an economic revolution," he said. "In fact, it's both."

Brilliant called for a modern-day equivalent of the 1960s-era civil-rights movement, rather than a government-led version of the Manhattan Project - nothing less, in fact, than "a change in human consciousness."

When it comes to developing alternative-energy sources and slowing the advance of global warming, said Brilliant, "The holy grail is making electricity from renewables cheaper than electricity from coal. And that means a whole new vocabulary - starting to think about black electricity versus green electricity, and a grid that can distinguish them and differentially price them." Like others on the panel, he cited the need to make the price of carbon-based fuels reflect the environmental costs.

Asked by Rose about nuclear power as a clean alternative to coal, Brilliant noted the extravagant costs associated with mining uranium, and the subsidies required by the nuclear industry to survive. "I don't think that most people would feel that nuclear is an option if you remove government funding," he said. "Here in the United States it wasn't the greenies that stopped nuclear energy. It was the green-eyeshade guys."

Rose said that parts of the summit, the fourth he's moderated for the 10-year-old TechNet, are likely to be broadcast on his eponymous PBS talk show at a future date.