Berkeleyan

|

Squeak Carnwath (Wendy Edelstein photo) |

Bunnies, boring objects, and the guilt-free zone

Squeak Carnwath celebrates symbols, colors, and the transformative power of art

![]()

| 31 October 2007

For Squeak Carnwath, inspiration for a painting might originate with something as ordinary as a grocery list. Or, she confesses, "it might come from fear that I'll never think of anything that I can paint again."

In paintings such as You Call This Happy (2001), above left, Squeak Carnwath employs a rabbit to exorcise a childhood wound. Her parents sometimes called her and her five siblings "dumb bunnies," she explains. "It was sort of affectionate, but not really." (Photo by M. Lee Fatherree / Courtesy Squeak Carnwath) |

Those many layers of under-painting "give a kind of vibrancy [to the canvas] that feels alive to me," says Carnwath, explaining her labor-intensive method. She likens the accretion of color to skin and the unevenness of pigmentation. "It's like all of our flaws. Nobody's perfect."

Those painstaking layers form a luminous backdrop on which Carnwath renders the gently imperfect familiar shapes and disarmingly childlike script for which she has become internationally known. Using lists, common objects, and jottings, the artist combines everyday "boring things" to explore modern life with humor and, often, Zen-like insight.

Into the abyss

For Carnwath, who holds an M.F.A. from California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts), the act of creation is fraught with contradictions. "I like to not know where I'm going with a painting," she explains. At the same time, it makes her feel afraid. "I love that part," she says with relish. "I also like thinking, 'This is the worst thing I could be doing; this is really hokey.'"

| See Squeak Squeak Carnwath's work is currently on view in several exhibits commemorating the first 100 years of the California College of the Arts (formerly the California College of Arts and Crafts): "Celebrating a Centennial: Contemporary Printmakers at CCA" at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, "Artists of Invention: A Century of CCA" at the Oakland Museum of California, and "SJMA Collects CCA: Works on Paper From the Permanent Collection" at the San Jose Museum of Art. Her work can also be viewed at the John Berggruen Galley in San Francisco and in "The Missing Piece: Artists and the Dalai Lama," a group show beginning Dec. 1 at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. And in spring 2009, the Oakland Museum will be presenting a 20-year survey of Carnwath's work. On the Berkeley campus, "Recent Works by Squeak Carnwath" can be seen through Friday, Nov. 2, at the Townsend Center in Stephens Hall. |

Carnwath is driven to reveal her inner self in her work, an impulse she credits to her mother, whom she calls a "fabulous negative role model." As a girl, Carnwath's mother wanted to be a writer or actor, career paths her father prohibited.

After her mother died, Carnwath and her siblings (she's the oldest of six) discovered a couple of short stories she'd written for a class. "They were horrible," Carnwath recalls, "because she didn't want to reveal anything about herself - either metaphorically or any other way. An artist has to be willing to reveal something, and that's the scary part. In some ways, [as an artist] you don't have any privacy, but that's also sort of exhilarating. I feel like making any kind of artwork is an act of generosity, so that somebody else can recognize themselves in it."

Symbols demystified

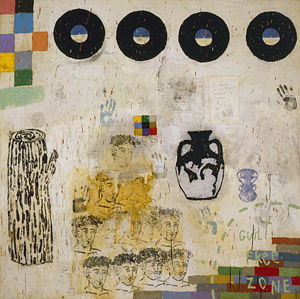

In most of Carnwath's work, viewers will see pictograms that run the gamut - an ancient Roman vase, LPs, Matt Groening-like rabbits, handprints, tree logs, crows, cakes, houses, and chairs. "I like the elasticity of symbols and the fact that people read them in different ways," she says.

And while to some viewers Carnwath's intent may be cryptic, she thinks there's too much focus in the art world on nailing down an artist's intentions. What an artist is trying to communicate is often personally driven, she says. "They're more interested in understanding their own narrative or their own psychology or the reasons why they're intrigued with a shape than they are with the viewer getting it exactly."

Carnwath views shapes and colors as "a subversive way for people to be hooked into an art object." After they're drawn in, "they will start free-associating to a thing that's familiar and can make sense of the imagery as it relates to their own life."

In Humans Are (2006) she uses a guilt-free zone to give herself a reprieve from the pesky emotion. (Photo by M. Lee Fatherree / Courtesy Squeak Carnwath) |

In paintings such as Humans Are (2006), left, the heads represent mourners inspired by images on tomb walls or old Etruscan frescoes. "They're like ancient witnesses to everything that's happened before us," she explains. The Portland vase is in memory of a departed friend, a ceramicist who loved that particular shape. Carnwath equates the log with the tree of life, good luck, or the impulse to touch wood.

Such symbols "all have multiple meanings," she says. "I'm very repetitive. I use them over and over until I get sick and tired of them."

Advice for artists

As a teacher, Carnwath wants to free her students from some of the constraints in contemporary art against which she has railed. "I was taught you can't write on your paintings, you can't have itty bitty things on huge canvases, you can't put teeny people on a huge canvas. Well, yes, you can. You can do anything," she says.

She tells her students to take risks. "Art is the last frontier, the only freedom. They should go for it. They should try to give themselves as much permission as they can to do anything that they want. That's hard to do. There are too many voices that we all have inside that say, 'Oh, no, you can't do that.'"

She also encourages her students to disagree with her opinions: "Art is not like other subjects where you learn a formula or a certain way to do research, and then you apply that methodology to your project. It's primary research. It can't be tested."

Carnwath's hope is that her own "primary research" offers viewers a chance to slow down and look at their own lives. "Maybe they'll think about what it means to be on the planet. I feel like we're supposed to work at being better human beings - that's our job, basically, and there are various ways people can do that. They can be nice to each other or try to have some kind of integrity - or, if they're artists, they can try to be generous in their artwork, so other people can get something back from it."

To learn more about the artist and her work, visit www.squeakcarnwath.com.