Berkeleyan

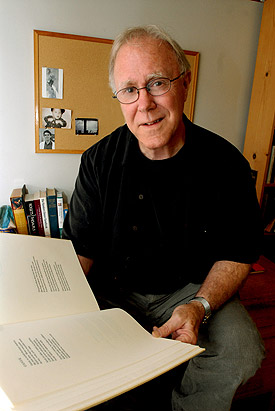

Robert Hass: Eight years of activism, writing, and reflection

The National Book Award finalist talks about big dams, martial bravery, and the color of flowers

![]()

08 November 2007

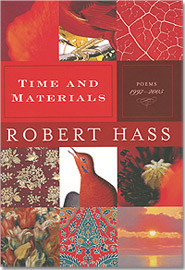

For the second time since 1996, Robert Hass, professor of English and former U.S. poet laureate, is a finalist for a National Book Award in poetry, for Time and Materials (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2007); the winners will be announced on Nov. 14. Hass spoke last week with Zack Rogow, a former College of Education staffer who for years coordinated the popular Lunch Poem series in Doe Library.

The Berkeleyan is grateful to Professor Hass for permission to reprint two of the poems he discusses with Rogow in this interview.

The subtitle of your nominated book is Poems 1997-2005. What were you doing during this eight-year span, and how may that have shaped these poems?

Some of the work I did during that period was environmental work. In 1995, with Pam Michael, I started a nonprofit to encourage children to make art and poetry about their watersheds, as a way of encouraging environmental education of an interdisciplinary kind in the schools. That program, the Watershed Project, is now 10 years old.

There's a poem in this book that made me think of the Watershed Project: "Ezra Pound's Proposition."

That poem also connects to another part of my work. I'm on the board of the International Rivers Network, which has been concerned particularly with where environmental issues meet human-rights issues around big-dam projects, many of which have proved destructive, displacing millions of people around the world. The IRN was founded to provide unbiased hydrological and financial analyses of these dam projects to the dam-affected people in the Third World. They've been enormously effective warriors in trying to help people acquire the tools to resist these projects.

There's a wonderful book by Catherine Caulfield, Masters of Deception, about the early years of the World Bank's relationship to these dam projects, when the thought was that all of this hydro-development was uncomplicated good. They were very casual about the human and environmental costs of some of these projects. An example Caulfield gives is that for one of the early projects, the Narmada Dam in India, the entire budget for dealing with the 1.7 million people who were being displaced from a traditional life that's 2,000 or 3,000 years old was a 1-rupee bus ticket!

There are poems in Time and Materials that are very inward-turned and self-reflective about the process of writing, moreso than in some of your previous books. At the same time, the book is also more outward-turned and political than some of your previous books. These movements seem to be in two opposite directions, and yet they seem to come together in this book.

Well, I hope they do! I think in the early years of these poems I was taking stock of my art and where I was in relation to it, and then the world turned. After the Bush administration had gotten us into two wars, it was hard not to be thinking about that.

Another set of poems is about another preoccupation during this time, which had to do with the nature of desire and its consequences....

That's something that maybe we are on the front lines of in California, where lifestyles seem to change first. Being a poet in California, you're in a good position to report on that.

It's true particularly of our generation, which began with a set of attitudes that hovered somewhere between bravery and self-indulgence. We're trying to work out authentic relationships - which, in the lives of my children and my children's friends, who had to negotiate this set of complications, meant a lot of exchanges along the lines of, "Susie's mom's lover is taking us there, and her dad will come pick us up."

It seems that when you're talking about the nature of desire, it's all bound up in this book with other human energies: violence, hunger, survival. Were you consciously thinking about exploring those as a group in this book?

No, I wasn't. With each of my books, my experience has kind of been writing one poem at a time. And then, at a certain point, I understand what my themes are, or begin to understand enough to see an arc. So I think these were my preoccupations during this period, and they braided together in this particular way.

A number of these poems are either "imitations," as you call them, or translations of work from poets writing in Swedish, German, or Latin. What made you decide to include those works with your own?

I included the versions of Horace's odes because it felt like part of my work.

You're talking about "Horace: Three Imitations."

Yes. I'd signed on to translate a few Horace poems for an editor in New York who wanted to do a new [edition of] Horace by a variety of hands. One of the most famous of the odes is the one that includes the line "Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" ... "it is sweet and fitting to die for one's country."

I didn't understand at the time that that was a poem about a Roman war in Iraq! It was about the Romans putting down Parthian insurgents in an imperialist war, which seemed too good to be true. And it's about the difference between the bravery of soldiers and the kind of courage that doesn't get you into unnecessary wars.

For the volume that was pure Horace I played it straight, but then I was able to do what I wanted with the poem after that, which was to put the Romans in tanks . . . drawing parallels by mixing the two languages.

|

You are an astute observer of flora and fauna, and nature, and their changes. Why is it important to you as a poet to get that right?

I've always had a love of the natural world. And my coming of age in the 1960s and '70s corresponded to a time when we began to become aware of how rapidly 20th-century civilization was depleting the gene pool of its intensity and variety of life forms. On the one hand, I like naming Californian places and things in my poems, I think because I grew up here, and as a child in school my readers were always books printed in Boston or New York in which Dick and Jane put on their boots and jumped up in down in fallen leaves, and there was snow and covered bridges and so on. I always had some feeling that the real world was over there. So it seemed important to be able to put in the names of California places, and California plants and animals - the feel of this life, and its weathers - into my poems. I used to think that was an achievement...

Another part of it is that, as things go, it feels urgent to be specific. I have a friend, [the poet] Linda Gregg, who has remarked to me about my poems that they don't describe the way that people really see. They see a yellow flower by the creek: They don't see a mimulus, they don't know the Latin name of the flower. And in that case all I can say is that I've wasted a lot of my time teaching myself the names of the flowers and the birds. So that is what I see.

In the poem "Art and Life," you meditate on Vermeer's great painting Woman Pouring Milk, and you say, "It is best, of course, to be the one engaged / And being thought of, to be the pouring of the milk." Yet it feels to me as though there's a great pleasure of observing and describing and imagining as well in your poetry.

This is like - it's not like, it is - Wallace Stevens saying, "I don't know which to prefer, the beauty of inflections, or the beauty of innuendoes. The blackbird whistling, or just after." The person in this poem thinks it's better to be the blackbird whistling, as a meditation on why we love to look at people unself-consciously performing ordinary actions. It's sort of a blessing, in Vermeer's paintings and much of the art that I admire - haiku is part of that tradition - to encounter ordinary people going about ordinary things; it seems an enormous gift. And the height and intensity of this gift demands a separation from it. It's a paradox we have to live with, in the same way that one might look at one of those endless French photographs of young lovers kissing by the river, and partly want to be one of the lovers: It's clearly better to be one of them, in a way, but on the other hand there's something great about being the person who sees that.

In that poem you question the reliability of the voice of the poet, the speaker of the poem. Why is that at issue?

It may have something to do with age. My sense of the instability of memory, and of the language in which we can recover it, has intensified. In some ways that's a gift as well; in some ways it's unbearable. This is one of Czeslaw Milosz' themes: He found it unbearable that the world disappeared, and that all that lived life turned into fraternity theme parties: a '20s or '30s party, or a '70s or '80s party. He had seen so much world go by, and so much world that had been mythologized, too. I notice that that's become one of my themes as well.

| Ezra Pound's Proposition Beauty is sexual, and sexuality Here is more or less how it works:

© Robert Hass, all rights reserved. Used with permission. |

| "Horace: Three Imitations" consists of three Odes, of which the following, discussed above by Hass, is number two: Odes, 3.2 Angustam amice pauperiem pati Let the young, toughened by a soldier’s training, Also to walk so easily under desert skies And say with a shudder: Pray God our boy It is sweet, and fit, to die for one’s country, Civic courage is a more complicated matter. The kind of courage death can’t claim Knowing when not to speak also has its virtue. They say the gods have been known

© Robert Hass, all rights reserved. Used with permission. |