Berkeleyan

Donald Kennedy on the control of scientific knowledge

The editor-in-chief of Science last week delivered the first of three 2007 Clark Kerr Lectures

![]()

| 08 November 2007

Editorializing in Science magazine earlier this year, Donald Kennedy voiced his support for congressional hearings into White House efforts "to modify or rewrite the scientific findings of agency scientists." He went on to raise concerns over a Bush administration initiative to boost the power of political appointees at the helms of federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Some, he wrote, "will see these events as a typical, garden-variety struggle between a Democratic Congress and the White House over the use of science in informing policy."

In fact, Kennedy insisted, the confrontation was "a struggle for authority between a presidency wanting control over information so that the public will accept its version of reality, and a Congress insistent on its responsibility to find facts needed to shape national policy."

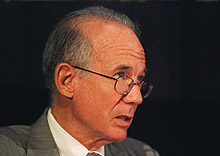

Kennedy, above, traced the state of university science to Vannevar Bush, an adviser in FDR's White House. (Peg Skorpinski photo) |

That struggle, he added, was at the core of America's democratic values. "Presidential claims to exclusive power over knowledge may sometimes be justifiable in our national interest," he wrote, "but we should not be misled. We are not an empire - and our president is neither an emperor nor, as author and historian Garry Wills reminds us, the commander-in-chief of anyone who doesn't happen to be in the army or navy."

The title of Kennedy's editorial, "Science, Information, and Power," could easily have been repurposed for a campus talk he gave last week in the first in a series of three Clark Kerr Lectures, a biennial event sponsored by the Center for Studies in Higher Education to honor the one-time UC president and Berkeley chancellor. The series, which in fact was titled "Science and the University: An Evolutionary Tale," was to continue Wednesday, Nov. 7, in Barrows Hall, with the final lecture scheduled for next week at UC Irvine.

A biologist who headed Stanford University from 1980 to 1992, Kennedy served as commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration under President Jimmy Carter and has been editor-in-chief at Science, the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, since 2000. On Wednesday he drew on his high-level experience in academia, government, and the scientific community to provide a historian's perspective on the evolving relationship between the practitioners of science and the policymakers who help shape the environments in which they work.

What Kennedy sees as "the pioneer spirit" embodied in university-based science research was conceived at the end of World War II, when Franklin Roosevelt's director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Vannevar Bush - "the other Bush," as Kennedy dubbed him - laid out his vision of postwar science in a report he called "Science, the Endless Frontier."

The metaphor, said Kennedy, "could scarcely have been more appropriate."

"The frontier, of course, brought back visions of an earlier American West, the West, indeed, of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark," Kennedy said, adding that Bush's framing of the issue "connoted exploration, but of a very particular kind - not a search for a specific goal, but rather a loosely guided expeditionary foray to find, describe, and ultimately understand what was new and therefore unknown."

Moreover, the metaphor "suggested not only unknown but unowned space, a common-pool resource inviting free intellectual access without the hindrance of proprietary interest. That was the power of the endless frontier."

Bush imagined a single agency, largely civilian controlled, that would oversee all the nation's scientific exploration, and noted the limited funding available for universities and research institutes: "If they are to meet the rapidly increasing demands of industry and government for new scientific knowledge," he wrote, "their basic research should be strengthened by the use of public funds."

That the reality only partially matched the vision can be seen today both in garden-variety struggles for control over information and in the tension between government and science in the wake of 9/11. The reasons, said Kennedy, date back to the postwar period, and Bush's inability to sell "his faith in the unity of science" - or his desire for civilian control over military research - to Roosevelt's successor in the White House, Harry Truman.

No success like failure

In a letter to Bush dated Nov. 17, 1944, Roosevelt noted that "the information, the techniques, and the research experience developed by the Office of Scientific Research and Development and by the thousands of scientists in the universities and in private industry should be used in the days of peace ahead for the improvement of the national health, the creation of new enterprises bringing new jobs, and the betterment of the national standard of living."

The president went on to ask Bush, as the OSRD's director, to recommend ways that the lessons learned during World War II could be "profitably employed in times of peace."

Bush responded with "Science, the Endless Frontier," which, Kennedy said, "moved the wartime military science machine into the universities, the very same places where the next generation of scientists were going to be trained. And that convergence was a key aspect of the Bush proposal."

The entity Bush proposed would be responsible for all areas of scientific investigation, including medical and military research - neither of which came to pass. On the military front, especially, Bush's political naiveté may have contributed to his inability to prevail in his fights with Truman and the Joint Chiefs of Staff for civilian control over military research.

In 1947, when Congress passed legislation to establish the OSRD's successor agency, the National Science Foundation, Truman went so far as to veto the bill, objecting to its delegation of appointment power to the volunteer, civilian members of the agency's oversight board.

The upshot, as Kennedy explained, was that the national medical-research enterprises previously supported by Bush's OSRD were eventually handed over to the National Institutes of Health, while research undertaken in the interest of national defense remained with such mission-based agencies as the Defense Department and the Atomic Energy Commission, the precursor to today's Department of Energy.

"In the view of many, the present situation is not conducive to a balanced portfolio of scientific investment," observed Kennedy, noting that the NIH budget of more than $28 billion dwarfs that of the NSF, which is funded at under $6 billion. But research for military needs, he added, is a "much larger problem."

Despite these "failures," Kennedy said, "'The Endless Frontier' did establish a really remarkable thing: It put U.S. research universities at the very heart of the nation's science efforts, encouraging the growth of physical infrastructure, and encouraging good ideas with generous project funding."

Above all, perhaps, Bush helped establish the notion of "a knowledge commons for science," including the principle that "scientific advances will proceed more rapidly with diffusion of knowledge than under a policy of continued restriction of knowledge now in our possession."

"Repeatedly," Kennedy said, Bush's groundbreaking report "pictures fundamental science as being done in the universities and in the endowed laboratories, and he characterizes industry and government laboratories as the sector that must take this basic knowledge and use it to create products and services for human use."

Things changed significantly, Kennedy added, with the passage of the so-called Bayh-Dole amendments in 1980, which opened the door for universities to hold patents on federally funded inventions and other intellectual property. "As for the relationship between the universities as the source of basic research and the commercial sector as the domain of application," he said, "that relationship has been significantly reworked, or even re-engineered, as the result of a dramatic shift in the role that government asserts with respect to intellectual property."

That, however, would be a topic for another day.