Berkeleyan

A passion for pachyderms

The Tang Center's Julie Barnett is on a crusade to save Asian elephants

![]()

| 28 November 2007

Among her colleagues at the Tang Center, primary-care nurse Julie Barnett is known as "elephant girl." Barnett earned her nickname because she's committed to aiding Asian elephants, a cause she came to several years ago after visiting a sanctuary for the abused mammals in northern Thailand.

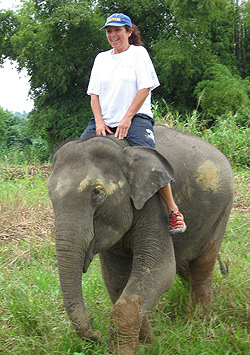

Julie Barnett rides Pang Lom, a 4-year-old elephant who was malnourished and frightened before being rescued from the streets and moved to an elephant sanctuary. (Photo courtesy Julie Barnett) |

That "cool day trip" opened her eyes to the plight of Asian elephants, whose numbers have dwindled to 40,000 worldwide (from an estimated population of 100,000 at the beginning of the 20th century). Loss of habitat, old age, few births, and many deaths have contributed to these losses among wild elephants, while their domestic counterparts suffer from poor nutrition and lack of veterinary care.

A key attraction in Thailand's tourist industry, Asian elephants are used to carry passengers in heavy riding chairs often on full-day or multi-day treks. While elephants are strong, their strength isn't centered in their back and joints. "They walk 10 to 12 hours a day," Barnett points out, "and some of them are carrying 1,000 pounds of people on their back in one of those baskets. So their health is terrible."

In Bangkok, elephants are made to stand in polluted streets with large sacks of bananas and sugar cane on their backs. Their handlers sell tourists and locals the opportunity to feed the animal what amounts to junk food for pachyderms for the equivalent of a few pennies.

Elephants are also the favorite workhorses of illegal timber harvesters in Thailand. Logging has been banned in Thailand since the 1980s, but teak loggers continue to operate. To avoid detection they force elephants to pull logs to pick-up points during the night. "A lot of the elephants are being fed bananas with amphetamines, so they're like meth addicts. They are often underfed and overworked, and become very thin and prone to injury," says Barnett.

Swimming with elephants

Since 2005, Barnett has journeyed to northern Thailand twice a year to volunteer with elephants rescued from such situations. Not surprisingly, the care and feeding of elephants is an involved undertaking.

At 7 a.m., volunteers hike to nearby fields and cut grass for their charges, who consume 500 pounds of food a day.

At Boon Lott's Elephant Sanctuary (www.blesele.com), Barnett's favorite shelter, volunteers ride the elephants to a nearby river, then bathe them twice a day. "It's a little scary, but it's also exhilarating," says Barnett of swimming with elephants. The volunteers scrub the elephants to rid their skin of parasites. The water helps keep the creatures cool in Thailand's humid climate.

Adventures are far from foreign to Barnett, who has traveled to many remote locations around the world. (Earlier this year, for example, she lived with a headhunter tribe in Borneo.) Nonetheless, her passion for the large mammals has taken her by surprise: Their "power and majesty" impress Barnett, and their gentleness deeply moves her. "When you're riding on them, you have nothing to hold on to. There's no saddle or reins ... you just sit right at their neck." Barnett marvels that the elephants - who weigh 10,000 pounds on average and stand the height of a one-story building - could easily throw her off and trample her, but they don't.

Barnett can recount tales of individual Asian elephants as if they were her own children. In 2006 she helped rescue Medo, a 30-year-old animal abused by loggers who persisted in using her for hauling even though a logging accident had maimed her two decades ago. Elephant-welfare agencies raise money to purchase such abused animals from their keepers.

"When the mahout [caretaker] brought Medo out of the forest, she had fresh blood on her head and had clearly been beaten," says Barnett. Medo's rescuers cajoled her into their truck, and then ferried her eight hours to the sanctuary over mountainous terrain. "Medo hadn't seen another elephant in about 10 years," says Barnett, explaining that elephants are pack animals who typically live together.

Once the animal arrived safely at its new home, Barnett got the opportunity to use her day job's skills. The sanctuary's volunteer veterinarian had learned she was a nurse. "We had to open up wounds and drain out the pus. It was like working on a person, except that Medo is huge."

Most of the half-dozen sanctuaries where Barnett has volunteered abut farmland. When the elephants are led to the jungle at night to sleep, they are secured to trees with long lengths of chain, because commodities such as rice, bananas, and papayas are planted nearby. "If they are not restrained, they can eat - and destroy - an entire season of crops in a night," she explains.

One of the elephants Barnett cared for this summer broke loose overnight, and began feeding at a nearby farm. A farmer discovered him, shot him in the head, and left him for dead.

When Barnett learned of his situation, the elephant was barely alive. "He had just been rescued four months before that from a life of terrible abuse," she says. "The Asian elephants are in so much trouble. It's very possible they could become extinct. It's my little crusade to help save them."