Berkeleyan

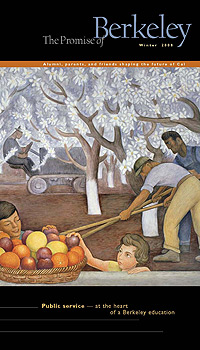

The Promise of Berkeley

Keeping the Cal family in touch

![]()

27 February 2008

Produced three times a year by the editorial-and-design team in University Relations, The Promise of Berkeley is a 32-page magazine about the campus's people and projects, designed to connect alumni, parents, and friends of the university. A typical issue may contain a message from Chancellor Birgeneau, photos of faculty and students accompanying brightly written stories about their work, and a range of colorful photos and graphics.

|

"There's so much to celebrate about Berkeley, and to share with our hundreds of thousands of alumni and friends," says Jane Goodman, who directs the editorial team that produces not only The Promise of Berkeley but a range of donor-directed materials. "Even publishing three times a year, it's impossible to squeeze more than a fraction of the campus stories we learn about into our pages. It makes our job that much more challenging, but it's also a reflection of Berkeley's diversity and excellence."

Each issue of The Promise of Berkeley is organized around a theme, usually one relating to a specific campus initiative, such as undergraduate and graduate education, faculty excellence, or green energy. The most recent issue, mailed to some 110,000 readers (and available online at promise.berkeley.edu), focuses on the theme of public service, a longstanding priority for Berkeley students and faculty alike - about whom Birgeneau writes, in his contribution to this issue, "Through the knowledge they help create and disseminate, and through direct leadership and volunteerism, they truly are reshaping the world by their efforts."

Four short articles from the current issue appear below, highlighting the public-service efforts of faculty, graduate students, and undergrads in a range of subject and geographical areas. Goodman notes that specific articles from the online version of the magazine (including its archived issues online) can be easily linked to and promoted by others on campus in e-mails or other online publications, "repurposing" the work for the benefit of all.

Are you being watched?

|

From the supermarket parking lot to a busy intersection, if you are in public, you are very likely under the gaze of video surveillance. But who is watching, and why? How can we prevent abuses of this technology?

Under the leadership of Clinical Professor Deirdre Mulligan, students at the Samuelson Law, Technology, and Public Policy Clinic at Boalt Hall School of Law are striving to answer these questions while working to fill a gaping policy vacuum. David Snyder, a third-year student at Boalt and clinic participant, says, "A lot of cities are really increasing use of cameras without a lot of thought about preventing nefarious uses."

Snyder and other students have helped California communities as disparate as Fresno and Richmond assess the impact of video surveillance on residents and develop clear guidelines for its use.

As cameras become more sophisticated, the issues - and potential solutions - become more complex. "These cases are at the boundaries of law and technological development," explains Mulligan. In fact, the clinic frequently works with the College of Engineering and School of Information to research the uses and abuses of surveillance, and to develop technological as well as legal safeguards.

This semester the clinic will be working with the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society (CITRIS) to evaluate the effectiveness and impact of San Francisco's surveillance program - research that Mulligan believes is crucial to the debate. "It's not just about privacy," she says. "It's about whether this is the right technology for the job."

Phone-fueled fluency

In India, where English is one of two national languages - and used in 90 percent of the country's indigenous Web content - English proficiency is critical for employment, upward mobility, and accessing technology. Yet English literacy remains out of reach for an estimated 160 million Indian children in rural areas and slums.

|

Combining market opportunity with educational need, Berkeley computer-science doctoral student Matthew Kam has been developing English-language learning games for cell phones, as part of a project called Mobile and Immersive Learning for Literacy in Emerging Economies (MILLEE), which was just awarded a sizable grant in a competition funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (See story).

In field studies, Kam and other MILLEE team members discovered that getting kids interested in playing with cell phones was easy. Making the lessons effective, however, meant localizing content and game design. To teach the concepts of "stop" and "go," for example, the design team initially used green and red traffic lights.

"The scenario was completely irrelevant," says Divya Ramachandran, a computer-science Ph.D. student who participated in field studies in northern India. "Many children there haven't driven in cars, and there aren't traffic lights everywhere." The solution was a picture of a traffic cop - still a common figure in India - using hand signals for stop and go.

So far MILLEE has focused on rural India, but the concept is applicable to other languages and developing regions. "It's so satisfying," says Ramachandran, "to use computers for public service, in the real world."

Volunteer vacations

Instead of spending spring or winter break sleeping in, socializing, or getting a tan, participants in the Cal Corps Public Service Center's Alternative Breaks program spend the week wrestling with immigration issues on the Tijuana border, helping build housing for migrant laborers in California's Central Valley, and contributing to the rebuilding of hurricane-ravaged New Orleans.

|

Each year some 4,400 Berkeley students initiate, promote, and operate a wide variety of service programs through Cal Corps, a one-stop shopping center that serves as a liaison between students and the community. With 300 partner agencies targeting K-12 education, health care, community development, and social justice, Cal Corps facilitates one-time events and ongoing programs, and supports faculty in community-based research.

Students seek out service opportunities not only because they look great on the résumé (they do) but because, as one participant in New Orleans said, it's "amazing, enlightening, effective - an unforgettable experience that contributes to one's growth and identity."

Everyone profits, says program director Megan Voorhees. "Faculty get re-energized, and community partners inspired. As a public institution, our call is to train young people to be effective leaders, to benefit others. Public service ensures that Berkeley is relevant to a lot of different audiences."

Creative survival in a concrete jungle

Stories of abuse or addiction among incarcerated women are bleak reminders of societal realities. But to Nina Billone, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies, these stories present powerful opportunities to create art.

|

Possessing lifelong experience in ensemble-based improvisational theater, Billone is interested in how the arts inspire the penal-welfare system - and the people within it - to change. Deeply committed to integrating theory and practice, she is volunteering with several Bay Area organizations as a scholar, collaborating artist, and activist.

"Theater has had a profound impact on me," says Billone. "Now I'm questioning what it can do for others."

Billone has worked primarily with The Medea Project: Theater for Incarcerated Women, founded by Rhodessa Jones in 1992. Comprising professional artists and women from the San Francisco County Jail, the group creates large-scale performances (both inside the jail and outside) that are based on their own life tales.

In 2006, Billone began translating the novel My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, by Nigerian author Amos Tutuola, into an urban American retelling called My Life in the Concrete Jungle. She met regularly with the core ensemble to discuss the book, lead theater games and writing exercises, and help Jones shape the show. Jones eventually named Billone assistant director.

"Nina brought a cool, intellectual, creative intensity to the project," says Jones. "The female offenders found her engaging, informative, and nurturing."

One challenge was moving the show away from personal testimony toward an ensemble piece. It continued to change until opening night.

"The final production was the icing on the cake. The real work happened during the process," says Billone. "Ultimately, it's about women saving their own lives. We call it creative survival."