Berkeleyan

|

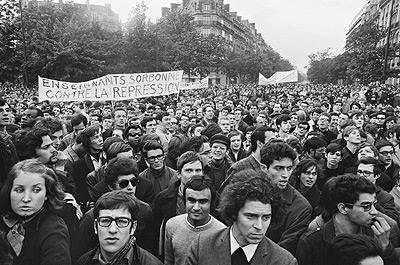

Throngs of students and workers marched through Paris on many occasions during May 1968, their numbers growing in number and intensity with each passing day. (All photos by Serge Hambourg, courtesy Hood Museum of Art) |

Anniversary of a rebellion

What veteran of ’60s protests can view Serge Hambourg’s photos and not murmur, ‘We’ll always have Paris’?

![]()

| 19 March 2008

|

“Protest in Paris 1968: Photographs by Serge Hambourg” is on view at the Berkeley Art Museum through June 1. The exhibition catalog is available at the Museum Store for $24.95.

Hambourg will give an artist’s talk in the museum’s Theater Gallery at 5 p.m. on Friday, April 4. Joining him will be Martin Jay, the Sidney Hellman Ehrman Professor of History, whose research interests include visual culture and late-modern Europe. Later that evening, at 9:15 p.m., the Pacific Film Archive, as part of its accompanying film series, “The Clash of ’68,” will screen a new print of Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise. For information, visit bampfa.berkeley.edu. |

But 1968 was also a meaningful year far beyond our borders, for reasons that had little to do with America’s multiple strains and stresses. There were popular revolts around the globe: in Mexico and Czechoslovakia, Senegal and India, Poland and Argentina. None, however, appeared to develop as rapidly, and to threaten the underpinnings of a major industrial economy so directly, as did the student protests in Paris that May, which in a matter of days engaged millions of French citizens, including a great many industrial workers, in mutual rebellion against the established order, threatening — for a brief but heady few weeks — to revolutionize the nation.

A number of the pictures taken by Serge Hambourg, a press photographer for the weekly magazine La nouvel observateur, during those eventful days make up “Protest in Paris 1968,” an exhibit on display through June 1 at the Berkeley Art Museum. The majority of the images, taken between May 9 and 13, capture the days of action and debate that followed the May 3 police attack on student demonstrators at the Sorbonne, which resulted in hundreds of injuries and arrests. Two nights of pitched battles between students and police across the Left Bank were followed by the declaration of a general strike across all of France; it began to seem likely that the government of President Charles de Gaulle would collapse as the nation’s economy, in essence, shut down.

Paris was no Berkeley

Viewing Hambourg’s images of marchers, onlookers, and police, exhibit visitors d’un certain age will notice dissimilarities between Paris ’68 and, say, Berkeley or Columbia in the same era. The protesters occupying Hambourg’s frame are, in the main, neat of dress and short of hair, resembling the best-and-brightest participants in Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement of four years earlier far more than the hippies and yippies who stood out on the campuses of “Amerika” ’68. Their banners, posters, and placards call for change not in their country’s foreign policy but in the hierarchical conditions under which French students studied and French labor labored. Indeed, it’s the partnership that developed between students and labor in France that May that seems most foreign to an American viewer accustomed to regarding campus protests, then as now, as the exclusive province of students, with passivity, if not outright hostility, the dominant response of working-class citizens.

|

The millions of factory workers who chose to ignore their titular leaders, joining forces with the protesting students of France as together they were caught up in the tide of events, were encouraged by the notion that radical reform of working conditions might be achieved by popular revolt. In the same manner, the mass of largely bourgeois students came to believe that by their own actions they could affect the structure and fundamental philosophy of higher education, which was characterized by one of their leaders, Alain Geismar, as “completely inadequate to an advanced country, with its compartmentalization of the various disciplines [and] its retention of a grading system dating from August Comte and of faculty structures inherited from the Empire.”

It’s the knowledge — and, for some viewers, the memory — of this attempt at unified political action on behalf of the nation’s exécutants (order-followers) against its dirigeants (order-givers) that infuses some of Hambourg’s photos with a certain wistfulness, even as they capture a nascent political movement in its dynamic, albeit brief, public flowering. One such image is reproduced on this page: It depicts the leading edge of a march passing before the building housing Socialist Party headquarters, to the façade of which is fastened a banner celebrating solidarity between students and workers — an alignment envisioned by only the most ideological among the U.S. students who marched for peace and social justice throughout the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Ultimately, the French rebellion of 1968 was short-lived, brought to an end by a confluence of events: negotiations between unions and the government, counter-demonstrations by Gaullists and other right-wing sympathizers, and the removal by police of protesters from the last contested sites in Paris. All of the government’s modest reforms and efforts at co-optation were achieved by mid-June, just a month after the height of the Paris protests.

Was it all for naught, then? Hambourg’s photos foreshadow little, except insofar as they conclude in this exhibit just at the point of Gaullist counter-revolt. Perhaps it is enough to suggest that something of the flavor and fervor of 1968, as it was experienced not just in Paris and Berkeley but around the world, still determines our collective memory of that year — a recollection that for many goes beyond sad memories of martyred leaders and blood-red streets, dwelling for as long on the hopes and dreams of those who were alive then, engaged in the work of conceiving and building a better world.