Berkeleyan

Obituary

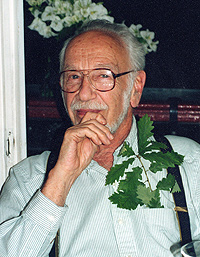

David Gale

![]()

02 April 2008

David Gale, a professor emeritus of mathematics (and a puzzle lover) who made fundamental contributions to economics and game theory, died March 7 in Berkeley following a heart attack. He was 86.

David Gale |

Gale, a resident of Berkeley and Paris, applied his lifelong love of mathematics and problem-solving to make discoveries that have been applied broadly within economics and operations research. His work has also had far-reaching implications for pure mathematics and computer science.

"David was known for his elegance, which is a term of honor for math arguments that go directly to the point, that are simple and, to our community, beautiful," said one of Gale's former students, Joel Sobel, a professor of economics at UC San Diego.

Gale's 1960 book The Theory of Linear Economic Models is a widely used reference work on linear optimization that brought to a broad audience ideas developed by Gale and his co-authors in the 1950s, Sobel said. In recognition of this work on the theory of optimization, Gale shared the 1980 John von Neumann Theory Prize with Harold Kuhn and Albert Tucker. According to the prize citation, "Their research played a seminal role in laying the foundations of game theory, linear and non-linear programming — work that continues to be of fundamental importance to modern operations research and management science."

Sobel noted that the school systems of New York and Boston now match students with schools using procedures that are intellectual descendants of research Gale completed with Lloyd Shapley, now professor emeritus of economics at UCLA. This research involved the so-called stable-matching or stable-marriage problem. Gale and Shapley proved that, given an equal number of men and women who rank one another in terms of romantic interest, it is possible to pair them in marriage such that no two people would rather be married to each other than to their partners. The researchers also provided an algorithmic procedure to find a stable marriage. Gale and Shapley's theoretical work on this problem legitimized a procedure used to match newly graduated doctors to hospital residency programs.

According to Sylvia Nasar's 1998 book A Beautiful Mind, Gale was one of the first people to recognize the significance of John Nash's concept of game-theoretic equilibrium. He also was an early contributor to general-equilibrium theory and solved the Ramsey problem of optimal-growth theory.

Gale was born in Manhattan in 1921 and grew up in and around New York City. He graduated from Swarthmore College with a B.A. in 1943, obtained an M.A. from the University of Michigan in 1947, and earned his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1949. After a yearlong stint as an instructor at Princeton, he joined the Brown University mathematics department in 1950, where he remained until 1965, except for a yearlong sabbatical at the Rand Corp. in Santa Monica. Following a yearlong Miller Professorship at Berkeley, he was appointed a full professor in both mathematics and operations research in 1966. He also was appointed to the economics faculty in 1967.

Gale was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1983, received the Lester Ford Prize in 1980, and was named a fellow of the Econometric Society, the Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He received a second Miller Professorship in 1971; a Fulbright Research Fellowship in Denmark in 1953, where he met his former wife, Julie Skeby, who died earlier this year; and two Guggenheim Fellowships, in 1962 and 1981.

"He thought math was beautiful, and he wanted people to understand that," said his daughter, Katharine Gale. "But he was emphatic that the way for people to get the beauty and elegance of mathematics was to engage in it, not just be told about it."

She recalled that her father would discuss his mathematical work at the dinner table and share with his children his fascination with chess puzzles, card games, puzzle blocks, and interlocking puzzles, as well as with all types of math games. Throughout his life, Gale would insist that visitors look at the newest puzzle he was working on. According to his daughter, just before his death Gale e-mailed a colleague to discuss the mathematics of Sudoku, a popular game where players place numbers on a nine-by-nine grid.

After his retirement from teaching, Gale began writing a recreational math column in the magazine Mathematical Intelligencer. He collected these columns in his 1998 book Tracking the Automatic Ant and Other Mathematical Explorations.

Gale's "intellectual depth, originality of insight, and thorough liveliness were apparent from the beginning and have remained a source of joy and inspiration to all of us. His life's influence is a permanent heritage," wrote Kenneth Arrow, professor emeritus of economics at Stanford University and 1972 winner of the Nobel Prize in economics.

In addition to his companion, the poet and literary critic Sandra Gilbert, Gale is survived by three daughters (Kirsten Gale Cutler of Santa Rosa, Karen Gale of Sacramento, and Katharine Gale of Berkeley) and a sister, Ellen Dunning of Peabody, Mass.

A memorial service is scheduled for 3 p.m. on Sunday, April 27, in the Great Hall of the Faculty Club. Donations in Gale's memory may be made to The David Gale Fund for Interactive Mathematics, which, in part, will maintain and grow Gale's online math museum, MathSite. Send contributions to University Relations, 2080 Addison St., Berkeley, CA 94720-4200.

- Robert Sanders