Berkeleyan

Shades of gray . . . with a touch of black-and-blue

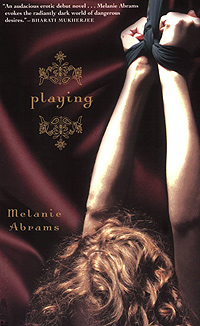

In her first novel, English lecturer Melanie Abrams takes a literary yet erotic approach to dominant/submissive sex

![]()

| 09 April 2008

“Well,” Devesh said. “Freud says all children have a desire to be punished, that it’s a normal stage in development.” He rested his hands under his head. “Don’t you remember wanting to be spanked?”

Of course she remembered, but she never imagined that other children envisioned the same things, soothed themselves to sleep with images of paddles and rulers and hairbrushes. She had thought these things for as long as she could remember and had hated it. What kid thinks these things? What kid wants them? Bad kids, she thought. And she had been a bad kid.

— from Playing, by Melanie Abrams

In her debut novel, English lecturer Melanie Abrams explores the complexities of dominant/submissive sex — a brave move for any writer.

Abrams received encouragement to tackle the sexually taboo subject from her husband, writer Vikram Chandra, who’s also a lecturer in the English department. “He said to me from the very beginning, ‘Write the book you need to write,’ ” says Abrams, who teaches creative writing. “That was the best advice I could possibly get, because, for whatever reason, this was the story I needed to tell.”

Melanie Abrams (Wendy Edelstein) |

Her baby’s arrival will keep Abrams from undertaking an extensive book tour, though some West Coast readings are scheduled, including an appearance next week at Story Hour, the recently launched campus prose series she and Chandra coordinate.

Playing’s protagonist, Josie, is at a decidedly different point in her life. A 27-year-old anthropology graduate student, Josie becomes consumed by her relationship with Devesh, a surgeon 10 years her senior, who introduces her to the pain and pleasures found at the receiving end of a cat o’ nine tails. Had she focused solely on the couple’s sexual relationship, Abrams could have succumbed to sensationalism; but that was never her intent. She set out to write a work both literary and erotic, one that avoids making the sex scenes gratuitous and exploitative.

For Abrams, the sex in Playing provides a way to explore the origins of Josie’s shame and guilt. Inspiration came from a segment on the radio program “This American Life” about a New York man who in the 1980s rigged an answering machine to receive callers’ anonymous confessions. Word of the machine spread, says Abrams, and many people phoned in to divest themselves of their peccadilloes and private crimes. Those messages remained confidential until the story aired on public radio.

One confession in particular sparked Abrams’ imagination. In it, a man confessed to perpetrating an irreparable act as a small child. “I wondered who that person with this amazing guilt and huge family secret would grow up to be,” says Abrams. Thus the idea for Josie was born.

Abrams also drew inspiration from contemporary writers Mary Gaitskill and Kathryn Harrison, both of whom traffic in quirky, edgy stories that explore the dark side of human nature, as well as from such erotic classics as The Story of O and Venus in Furs. For aid with the childhood elements in her story, she found helpful examples of youthful characters in Donna Tartt’s The Little Friend (“the [12-year-old protagonist’s] point of view is so right-on and excellent”) and Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.

Avoiding pigeonholes

Josie’s early years figure into Abrams’ story. So does her relationship as nanny to Tyler, a 6-year-old boy who possesses the ability to recite such facts as “Australia is two point nine six seven million square miles and is located on the Indo-Australian Plate.” When Tyler is agitated, Josie can calm him by turning his focus to figures and data. Though Abrams acknowledges that Tyler is “not a normal kid,” she wanted to avoid labels such as Asperger syndrome — a disorder characterized by abnormal social interactions and repetitive behavior.

In the same way that she’s reluctant to pigeonhole Tyler with a psychological diagnosis, Abrams resists labeling Josie and Devesh’s bedroom activities as sadomasochistic. “The definition of sadomasochism is getting pleasure from pain, and I think, particularly for Josie, it’s not completely pleasurable,” she explains.

|

In fact, Josie seeks out the pain in her sexual games with Devesh as a form of atonement. “She’s trying to exorcise her guilt through this punishment, but that doesn’t work, because it’s not real punishment,” observes Abrams, who says she’s gotten a lot of questions about the book’s sexual violence. “I think for Josie some of the violence and sexuality are redemptive in a good way” — though not all of it is, she adds.

Abrams, who says she’s interested in looking at “areas of gray — not black and white,” allows that there are negative repercussions to Josie channeling her guilt and shame into her play with Devesh. “By the end, she’s realized — and maybe the readers do too — that if you can’t see some of this [sex play] as positive, at least you can see that it just is and avoid judging it. Whether it’s good or bad, this is who she is, and she has to accept it.”

Abrams says it’s easy for her to understand how an event in one’s past could fuel a person’s desire to engage in such activities. She takes issue, however, with the notion that’s been popularized in this psychologically aware age that all abnormal behavior can be traced back to and explained by our past. For Josie, she says, “it is her past that led her to this place, but perhaps without it, she still would be prone to this kind of erotic desire.”

Writing about dominant/submissive sex isn’t the only gutsy thing Abrams does in Playing. By making her couple an American woman and an Indian man, she leaves herself open to the question, “How autobiographical is your novel?” Abrams understands the impulse behind the query: “It’s the same question I would have. It’s the human desire to know the background of people’s lives.”

Abrams anticipates the question in a Q&A on her website, and quotes Birds of America author Lorrie Moore on the subject of truth and writing: “…the proper relationship of a writer to his or her own life is similar to a cook with a cupboard. What the cook makes from the cupboard is not the same thing as what’s in the cupboard.” Abrams adds, “Let’s just say that my cupboard is full of all kinds of interesting things, but I’ll leave the reader to speculate if any of them made it directly into the book.”

Perhaps a better question than whether her story contains threads of her own experience is why she gave her male character an Indian name. Abrams says she wanted to introduce an Eastern view to the story as a counterpoint to Josie’s obsession with being punished for her sins, so she created an Indian character.

“The idea of karma, that you’ll keep paying for your sins forever and ever, is extremely scary to Josie,” says Abrams. Devesh provided a way for Abrams to express the idea that “some things just are. There’s not an explanation for everything.”

Abrams will be reading at Story Hour on Thursday, April 17, at 5 p.m. in 190 Doe Library, and at Cody’s Books, 2201 Shattuck Ave., on Wednesday, April 23, at 7 p.m.

For information about the author, visit melanieabrams.com.