Berkeleyan

Quok Shee on Angel Island

A new book by Haas administrator Robert Barde tells a sorry tale of immigration, American-style

![]()

| 30 April 2008

Quok Shee, just 4-foot-9 and 20 years old, landed in San Francisco from Hong Kong on Sept. 1, 1916, with $10 to her name and Chew Hoy Quong by her side. Chew, an established Chinatown herb merchant, was a legal U.S. resident and, if their story was true, Quok’s new husband.

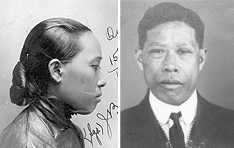

Quok Shee and Chew Hoy Quong, as they appeared in photos on health certificates issued in Hong Kong before they sailed for San Francisco in 1916. (Source: National Archives and Records Administration) |

Immigration authorities had their suspicions. Chew was 56; they called him the “alleged husband.” And for the next 20½ months they held Quok Shee in captivity on Angel Island while she fought in court for her right to enter the United States as Chew’s wife.

Of the 200,000 immigrants who passed through on Angel Island from 1910 to 1940, none was held longer than Quok Shee. Their torment has been told most eloquently in the wrenching poems they left carved in their prison’s walls.

Her story is unique only in the length of her long, lonely stay in the barracks at Angel Island. But it is also a universal tale of the immigrant experience on the West Coast during the era of the Chinese Exclusion Act and all the anti-immigration laws that followed it, says Robert Barde, a dedicated historian of immigration who works on campus as deputy director of the Institute of Business and Economic Research

(IBER), an Organized Research Unit that operates out of the Haas School of Business.

The notion that Angel Island served as the “Ellis Island of the West,” the Pacific equivalent of the New York entry point that welcomed some 12 to 17 million immigrants to the United States from 1892 to 1956, couldn’t be less true, Barde says in his new book, Immigration at the Golden Gate: Passenger Ships, Exclusion, and Angel Island (Praeger Publishers).

Now a state park whose tranquil beauty attracts more hikers than historians, Angel Island’s present belies a dark past: Its old immigration station existed to keep out Asian newcomers, not to welcome them.

Barde delves deep into Quok Shee’s fascinating case file — why did she fight so hard? why did the authorities? — both to tell the story of Angel Island and to illuminate an era of outright, legal discrimination against Asian immigrants.

It’s a cautionary tale that echoes today.

“It’s not only about Chinese immigration; it’s about American immigration,” Barde contends. The same issues raised by Quok Shee’s story are relevant in the ongoing national struggle over immigration into the United States.

“The immigration industry is still here,” Barde argues. “The notion of detention centers is still here, [along with questions about] what rights people have when they arrive here, how they should be treated.

“All these questions are very much still with us.”

Barde’s work at IBER sparked his interest in immigration research, and his research led him to examine his own life as someone who has migrated to the United States twice himself.

Robert Barde, deputy director of the Institute of Business and Economic Research at the Haas School of Business and author of Immigration at the Golden Gate. (Deborah Stalford photo) |

Barde’s experiences as an immigrant were nothing like the ones he writes about — he was already a U.S. citizen when he arrived, and moving to Toronto and back (as a Canadian citizen) were easy transitions because he spoke the language and had family and friends on both sides of the border.

But they help inform his book, as do the stories he’s dug up about his own relatives and his wife’s.

The shame of detention, for example, comes up in the story of May Ling’s China-born father, a poor village boy who arrived in 1917 and ended up at Columbia University. He never mentioned to the family that he’d once spent a brief time on Angel Island upon returning to the United States from a conference in Honolulu.

“It was the stigma of not being powerful enough or of high-enough status to avoid going to Angel Island,” explains Barde, who learned about the incident during his research for the book.

TV, art, and statistics

After an early career creating documentaries on Africa for educational TV and running an African-art gallery, Barde’s interest in immigration caught fire at Berkeley, where he first worked as program representative in the Center for Middle Eastern Studies before moving to the business school as an academic coordinator at IBER. Richard Sutch, an economics professor and director of IBER before moving to UC Riverside, invited him to work on the “International Migration” chapter of Historical Statistics of the United States: Millennial Edition (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

That assignment led Barde to the Pacific Region branch of the National Archives and Records Administration in San Bruno. Looking for immigration statistics, he learned from archivist Neil Thomsen that the storage shelves there were full of the investigative case stories of immigrants questioned at Angel Island from 1882 until the 1950s. Barde asked to see one.

Thomsen looked around and grabbed the first file he saw, lying on a nearby desk. It was Quok Shee’s.

“One hundred and fifty pages, filled with more drama than I could have invented had I tried to write her life as a novel,” Barde recounts in his book.

Chew, a legal resident of the U.S., said he had gone back to Hong Kong to find a bride, and had married the young Quok Shee. The two had lived together for six months before boarding the Nippon Maru steamship for San Francisco. As his wife, Quok Shee was entitled to enter the country.

But those were the days of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a racist law that Congress passed amid fear-mongering over the wave of Asian immigration that started with the Gold Rush. Local immigration officials were extremely cooperative when it came to enforcing the act’s harshest provisions.

Quok Shee and Chew suffered through long, repeated interrogations, and their stories bore up well — except for the tiniest of details. Was their clock made of wood (as one said) or metal (as the other did)? On such things hinged her ongoing incarceration.

Authorities hid the fact that they had a secret informer, still unidentified, who had alleged that Chew was bringing this young woman to work as a prostitute.

Quok Shee endured more than 600 lonely, deprived days in the Angel Island barracks, until the courts rendered their final judgment. (Those who haven’t read the book, or a shorter article about her life that Barde published earlier, will find no spoilers here.)

John Birge Sawyer (with clipboard), an Immigration Service inspector on Angel Island from 1916-18, and an interpreter interrogate Chinese immigrants arriving by ship, circa 1904-10. (Courtesy Bancroft Library) |

Packed around the drama are chapters that paint the full picture of immigration at the time. They’re told as history, but in a recent interview Barde fleshed out their links to the current day, particularly in the arena of anti-immigration law.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, an extreme law that Barde believes could never be passed today, was the first of that era’s legislative attacks on “undesirable” immigrants. Twenty-five years later Japanese immigrants were targeted, in a 1907 “gentlemen’s agreement” between governments; then, in 1917 the laws were broadened further to cover most Asians. By the early 1920s the National Origins Act set up quotas that favored white immigrants and set numbers as low as 100 a year for many countries outside the Western Hemisphere.

Another piece of the story is the immigration industry, at the time centered around big steamship lines, owned by Caucasians (and sometimes Asians) who employed multi-ethnic crews to transport immigrants across the Pacific.

“They wouldn’t call it a multicultural globalized industry in those days, but that’s what it was and that’s what it is now,” Barde says. Despite all the lurid tales of coyotes leading Mexican immigrants across the desert, he adds, most immigrants arrive legally on airplanes, trains, buses, and (sometimes) ships.

Trampling the most vulnerable

The best-known ship back then was the Nippon Maru, which transported Quok Shee and later earned infamy as the carrier of the first plague outbreak to hit North America, setting off a national panic; Asians, who were its only victims, bore the brunt of the overreaction.

“If you change ‘plague’ to ‘SARS,’ you’ve got a very similar story,” Barde points out. “In a panic, the most vulnerable people get trampled first.”

An intricate governmental apparatus grew up to enforce immigration laws — officials, inspectors, interpreters, and lawyers. Barde tells that story through the life of John Birge Sawyer, one of San Francisco’s most stalwart enforcers of the immigration laws then in effect.

“This was a really nice man,” Barde says. “He was straightforward and honest, he wanted to do good in the world. I think this is true of a lot of the immigration service today.

“But that doesn’t mean bad things don’t happen to the people in their charge.”

|

While Immigration at the Golden Gate leaves most of its leaps to the present day up to its readers, its epilogue tells a chilling story that makes it clear that detention in primitive conditions is in no way a thing of the past.

Mubenga Kanyinda, a Congolese man who arrived at New York’s JFK International Airport seeking asylum as a refugee facing persecution, found himself detained in a 200-bed jail run by the Wackenhut Corporation for U.S. immigration authorities. Jammed 40 to a room, with no windows, the prisoners lived under the eye of armed guards and cameras at all times.

His story, as told to the New York Times, could have been Quok Shee’s on Angel Island. Asked if he was tortured, he is quoted as saying: “Being in detention is a kind of torture. There is physical torture, and then there is the torture of one’s morale.”

Kanyinda spent nine months in the center. That was just eight years ago.

His tale and Quok Shee’s share a common lesson, Barde says — “that the immigration apparatus needs surveillance. There are going to be abuses, just because there are so many vulnerable people going through the system.”

American attitudes about people from other places, especially non-whites, Barde adds, haven’t really changed much since the days of Quok Shee and the Chinese Exclusion Act. “The particular object of anti-immigration feelings has changed,” he observes, “because immigration streams are a little different now. But the way resident whites look at the newcomers is pretty similar.”

The detention barracks on Angel Island, currently being renovated, are scheduled to reopen to the public in February 2009. For information, visit www.angelisland.org/immigr02.html.