Berkeleyan

Games aside, the real Olympic challenge is engaging with China

Scholars and artists depict a race against the Asian nation’s rising carbon emissions and unsustainable development

![]()

| 08 May 2008

The Olympics are “a profoundly un-Chinese event, alien to the deepest currents of traditional Chinese culture,” according to David Johnson, a veteran Berkeley professor of Chinese history. He reminded a campus symposium last Thursday that while competition lay at the very heart of ancient Greek culture — which idealized the “sovereign self,” lionized its greatest athletes, and sang epic poems to glorify its most valiant warriors — classical China had little notion of winners and losers. Its people valued the group over the individual and regarded virtue as an absolute standard, not a relative one.

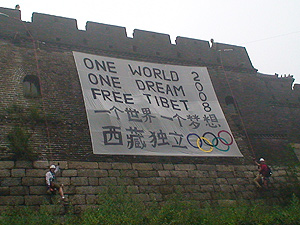

On the eve of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, China has captured the world’s attention — including, to its dismay, that of pro-Tibet activists. (Students for a Free Tibet photo) |

“That footraces by naked men could be an important part of communal rituals would have been incomprehensible and deeply shocking to the Chinese of the time of the great [ancient] philosophers,” declared Johnson. “Competition and striving for victory, the desire to defeat one’s peers, would have been repugnant.”

China, of course, has undergone a few changes since classical times — beginning in the 19th century, “when the Western world came knocking on China’s gates in a big way,” Johnson said, and “eventually broke them open and came rushing through.” And those changes will be on display as never before come August, when the 2008 Olympic Games kick off in Beijing.

For anyone seeking a peek into China’s dizzying transformation from Confucianism to Soviet-style socialism to global capitalism — and, perhaps, a middle ground between Olympian hype and the opprobrium being heaped on the Far Eastern superpower by human-rights activists of various stripes — the place to be last week was the Institute of East Asian Studies. Featuring perspectives ranging from the scholarly to the artistic, “A Beijing Olympics Primer: Place, Performance, and Performative Space” was a five-hour mini-marathon of insights into China’s environmental problems and policies, its approach to urban development, and a form of progress Confucius would surely find shocking — its evolving view of the human body.

If there was a common thread to the dozen-plus presentations — many of which ignored the Games themselves, using them mainly as a jumping-off point for discussions of concerns not directly related to sports — it was the need to engage with China rather than to further isolate it, as some seem to be advocating, over such international causes celébrés as its 50-year occupation of Tibet, its support for the repressive regimes of Myanmar and Sudan, and continuing human-rights violations within its own borders.

To Robert Collier, a visiting scholar at the Goldman School of Public Policy and former San Francisco Chronicle foreign-affairs reporter, the Olympics represent “a battleground” between engagement and confrontation with China. Collier, who is working on a book about the manufacturing giant’s role in global warming, noted the alarming increases in its carbon emissions — projected to more than double the total potential reductions by signatories to the Kyoto protocols — as it races toward ever-greater industrialization and moves from bicycles to automobiles as its chief means of transportation. But China, he argued, lacks the ability to rein in emissions without help from the international community.

“China-bashing is now an Olympic sport,” lamented Collier, a distance runner who recounted, from painful personal experience, the head-pounding effects of jogging in Beijing’s heavily polluted air. Referring to the country’s fiercely nationalistic reaction to criticism by outsiders, he said China’s leaders fear a “George Soros-CIA plot” — discordant as such a partnership might sound to Western ears — to use NGOs to help subvert the government. And he warned that if the “train-wreck political clash” continues between human-rights activists and the country’s rulers, such suspicions could extend to environmental advocates as well. He called instead for stepped-up engagement by the U.S. and other industrialized nations to work with the Chinese government to find ways to slow its output of greenhouse gases.

“The data,” he said, “show that it is an imperative of survival.”

The point was underscored by Nan Zhou, a research associate with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, who noted that in the perverse competition for the title of world’s top carbon-dioxide emitter, China surpassed the U.S. in 2006. Turning to an issue of domestic survival, Chi-Yuen Wang, a Berkeley professor of earth and planetary science, described the severe water shortages facing residents in the northern portions of China, and the devastating ecological and economic impacts of the country’s massive water-transport projects. Adding to its problems, he said, China is “working furiously” to ensure that enough water is transported to Beijing in time for the Olympics.

A ray of hope for China’s future was supplied by Harrison Fraker, dean of the College of Environmental Design, in the form of a sustainable building model he calls the EcoBlock. Envisioned as an alternative to China’s ubiquitous “superblocks” — huge, gated communities with up to 10,000 residential units that are springing up across the country at a rate of more than 10 a day — the EcoBlock is designed as a small neighborhood, generating its own electricity, processing its own water and waste, and offering green spaces and other amenities close enough to reach by foot or bicycle.

Fraker, who’s been traveling to China since 1998, described one visit to a superblock so sprawling that he had to walk three-quarters of a mile simply to find the entrance. The Qingdao Sustainable Neighborhood Project, in eastern Shandong province — the city is better-known here as Tsingtao, home of the brewery that bears its name — is based on the EcoBlock concept, developed by Fraker and his architectural students at Berkeley.

Writer Andrew Lam, a frequent contributor to NPR’s All Things Considered, celebrated China’s sexual revolution, part of a cultural renaissance he said is serving to challenge the state in much the same way as the ’60s counterculture did in the West. Choreographer Margaret Jenkins, by contrast, described her experience teaching modern dance in Hong Kong, Guangzhou, and Beijing in 2004, where students were “amazingly trained” technically but struggled with interpretation and creative expression. The experience led to her next project, Other Suns, a collaboration with the Guangdong Modern Dance Company.

The Olympics, suggested Johnson, stand as a sort of crossroads, a playing-out of the “deep tension in China between two ways of living.” On one side is the classical view “in which competition is not idealized,” and there are “neither winners nor losers.” On the other, “competition, especially between nations, is the guiding value, and there must be winners and losers.”

“That,” he added, “is why the existence of the Beijing Olympics may not be cause for undiluted celebration.”

The symposium was sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies, the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, the Center for Chinese Studies, and California magazine, whose current issue — online at alumni.berkeley.edu/california/main.asp — includes articles and photographs by several of the event’s participants. For more on the Qingdao EcoBlock project, visit greendragonfilm.com/qingdao_ecoblock_project.html.